Clin. Med. 2019, 8(1), 91; doi:10.3390/jcm8010091

Rubén de Alarcón 1 , Javier I. de la Iglesia 1 , Nerea M. Casado 1 and Angel L. Montejo 1,2,*

1 Psychiatry Service, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca, Institute of Biomedical Research of Salamanca (IBSAL), 37007 Salamanca, Spain

2 University of Salamanca, EUEF, 37007 Salamanca, Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

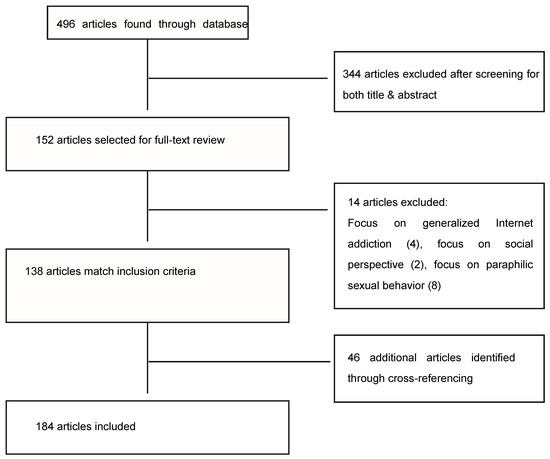

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiology

The vast majority of studies pertaining POPU or hypersexual behavior prevalence use convenience samples to measure it, usually finding, despite population differences, that very few users consider this habit an addiction, and even when they do, even fewer consider that this could have a negative effect on them. Some examples:

(1) A study assessing behavioral addictions among substance users, found that only 9.80% out of 51 participants considered they had an addiction to sex or pornography [36].

(2) A Swedish study that recruited a sample of 1913 participants through a web questionnaire, 7.6% reported some Internet sexual problem and 4.5% indicated feeling ‘addicted’ to Internet for love and sexual purposes, and that this was a ‘big problem’ [17].

(3) A Spanish study with a sample of 1557 college students found that 8.6% was in a potential risk of developing a pathological usage of online pornography, but that the actual pathological user prevalence was 0.7% [37].

3.2. Ethiopathogenical and Diagnostic Conceptualization

3.3. Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of POPU can be summed up in three key points:

-

Erectile dysfunction: while some studies have found little evidence of the association between pornography use and sexual dysfunction [33], others propose that the rise in pornography use may be the key factor explaining the sharp rise in erectile dysfunction among young people [80]. In one study, 60% of patients who suffered sexual dysfunction with a real partner, characteristically did not have this problem with pornography [8]. Some argue that causation between pornography use and sexual dysfunction is difficult to establish, since true controls not exposed to pornography are rare to find [81] and have proposed a possible research design in this regard.

-

Psychosexual dissatisfaction: pornography use has been associated with sexual dissatisfaction and sexual dysfunction, for both males and females [82], being more critical of one’s body or their partner’s, increased performance pressure and less actual sex [83], having more sexual partners and engaging in paid sex behavior [34]. This impact is especially noted in relationships when it is one sided [84], in a very similar way to marijuana use, sharing key factors like higher secrecy [85]. These studies are based on regular non-pathological pornography use, but online pornography may not have harmful effects by itself, only when it has become an addiction [24]. This can explain the relationship between the use of female-centric pornography and more positive outcomes for women [86].

-

Comorbidities: hypersexual behavior has been associated with anxiety disorder, followed by mood disorder, substance use disorder and sexual dysfunction [87]. These findings also apply to POPU [88], also being associated with smoking, drinking alcohol or coffee, substance abuse [41] and problematic video-game use [89,90].

3.4. Neurobiological Evidence Supporting Addiction Model

Major brain changes observed across substance addicts lay the groundwork for the future research of addictive behaviors [95], including:

3.5. Neuropsychological Evidence

3.6. Prognosis

3.7. Assessment Tools

3.8. Treatment

3.8.1. Pharmacological Approaches

3.8.2. Psychotherapeutic Approaches

4. Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatry Association. Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales, 5th ed.; Panamericana: Madrid, España, 2014; pp. 585–589. ISBN 978-84-9835-810-0. [Google Scholar]

- Love, T.; Laier, C.; Brand, M.; Hatch, L.; Hajela, R. Neuroscience of Internet Pornography Addiction: A Review and Update. Behav. Sci. (Basel) 2015, 5, 388–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmquist, J.; Shorey, R.C.; Anderson, S.; Stuart, G.L. A preliminary investigation of the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and compulsive sexual behaviors in a substance-dependent population. J. Subst. Use 2016, 21, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, S.R.; Lochner, C.; Stein, D.J.; Goudriaan, A.E.; van Holst, R.J.; Zohar, J.; Grant, J.E. Behavioural addiction-A rising tide? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, K.; Badgaiyan, R.D.; Gold, M.S. Hypersexuality Addiction and Withdrawal: Phenomenology, Neurogenetics and Epigenetics. Cureus 2015, 7, e348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, A.; Dawson, D.L.; Nair, R. das Pornography Addiction in Adults: A Systematic Review of Definitions and Reported Impact. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 760–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karila, L.; Wéry, A.; Weinstein, A.; Cottencin, O.; Petit, A.; Reynaud, M.; Billieux, J. Sexual addiction or hypersexual disorder: Different terms for the same problem? A review of the literature. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 4012–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voon, V.; Mole, T.B.; Banca, P.; Porter, L.; Morris, L.; Mitchell, S.; Lapa, T.R.; Karr, J.; Harrison, N.A.; Potenza, M.N.; et al. Neural correlates of sexual cue reactivity in individuals with and without compulsive sexual behaviours. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wéry, A.; Billieux, J. Problematic cybersex: Conceptualization, assessment, and treatment. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.D.; Thibaut, F. Sexual addictions. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2010, 36, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.A. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2001, 17, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, K.; Treder, M.S.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Kiraly, F.; Redden, S.A.; Stein, D.J.; Lochner, C.; Grant, J.E. Problematic internet use as an age-related multifaceted problem: Evidence from a two-site survey. Addict. Behav. 2018, 81, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A.; Delmonico, D.L.; Griffin-Shelley, E.; Mathy, R.M. Online Sexual Activity: An Examination of Potentially Problematic Behaviors. Sex. Addict. Compuls. 2004, 11, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, N.M. The internet’s impact on sexuality: A critical review of 15 years of research. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, W.A.; Barak, A. Internet Pornography: A Social Psychological Perspective on Internet Sexuality. J. Sex. Res. 2001, 38, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, E.; Carpenter, D.; Graham, C.A. Selecting films for sex research: Gender differences in erotic film preference. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2003, 32, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, M.W.; Månsson, S.-A.; Daneback, K. Prevalence, severity, and correlates of problematic sexual Internet use in Swedish men and women. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2012, 41, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemersma, J.; Sytsma, M. A New Generation of Sexual Addiction. Sex. Addict. Compuls. 2013, 20, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyens, I.; Eggermont, S. Prevalence and Predictors of Text-Based and Visually Explicit Cybersex among Adolescents. Young 2014, 22, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, H.; Kraus, S. The relationship of “passionate attachment” for pornography with sexual compulsivity, frequency of use, and craving for pornography. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, H. Technological change and sexual disorder. Addiction 2016, 111, 2108–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A. Sexuality and the Internet: Surfing into the New Millennium. CyberPsychol. Behav. 1998, 1, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.; Scherer, C.R.; Boies, S.C.; Gordon, B.L. Sexuality on the Internet: From sexual exploration to pathological expression. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 1999, 30, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, C.; Hodgins, D.C. Examining Correlates of Problematic Internet Pornography Use Among University Students. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pornhub Insights: 2017 Year in Review. Available online: https://www.pornhub.com/insights/2017-year-in-review (accessed on 15 April 2018).

- Litras, A.; Latreille, S.; Temple-Smith, M. Dr Google, porn and friend-of-a-friend: Where are young men really getting their sexual health information? Sex. Health 2015, 12, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimbardo, P.; Wilson, G.; Coulombe, N. How Porn Is Messing with Your Manhood. Available online: https://www.skeptic.com/reading_room/how-porn-is-messing-with-your-manhood/ (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Pizzol, D.; Bertoldo, A.; Foresta, C. Adolescents and web porn: A new era of sexuality. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2016, 28, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prins, J.; Blanker, M.H.; Bohnen, A.M.; Thomas, S.; Bosch, J.L.H.R. Prevalence of erectile dysfunction: A systematic review of population-based studies. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2002, 14, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mialon, A.; Berchtold, A.; Michaud, P.-A.; Gmel, G.; Suris, J.-C. Sexual dysfunctions among young men: Prevalence and associated factors. J. Adolesc. Health 2012, 51, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, L.F.; Brotto, L.A.; Byers, E.S.; Majerovich, J.A.; Wuest, J.A. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual functioning among sexually experienced middle to late adolescents. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, S.L.; Redmond, S.; Hassan, A.M. Sexual functioning in military personnel: Preliminary estimates and predictors. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 2537–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landripet, I.; Štulhofer, A. Is Pornography Use Associated with Sexual Difficulties and Dysfunctions among Younger Heterosexual Men? J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.J. U.S. males and pornography, 1973–2010: Consumption, predictors, correlates. J. Sex. Res. 2013, 50, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, J.; Patterson, R.; Regnerus, M.; Walley, J. How Much More XXX is Generation X Consuming? Evidence of Changing Attitudes and Behaviors Related to Pornography Since 1973. J. Sex Res. 2015, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najavits, L.; Lung, J.; Froias, A.; Paull, N.; Bailey, G. A study of multiple behavioral addictions in a substance abuse sample. Subst. Use Misuse 2014, 49, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester-Arnal, R.; Castro Calvo, J.; Gil-Llario, M.D.; Gil-Julia, B. Cybersex Addiction: A Study on Spanish College Students. J. Sex. Marital Ther. 2017, 43, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rissel, C.; Richters, J.; de Visser, R.O.; McKee, A.; Yeung, A.; Caruana, T. A Profile of Pornography Users in Australia: Findings From the Second Australian Study of Health and Relationships. J. Sex. Res. 2017, 54, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skegg, K.; Nada-Raja, S.; Dickson, N.; Paul, C. Perceived “Out of Control” Sexual Behavior in a Cohort of Young Adults from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010, 39, 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Štulhofer, A.; Jurin, T.; Briken, P. Is High Sexual Desire a Facet of Male Hypersexuality? Results from an Online Study. J. Sex. Marital Ther. 2016, 42, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangos, C.C.; Frangos, C.C.; Sotiropoulos, I. Problematic Internet Use among Greek university students: An ordinal logistic regression with risk factors of negative psychological beliefs, pornographic sites, and online games. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré, J.M.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Granero, R.; Aragay, N.; Mallorquí-Bague, N.; Ferrer, V.; More, A.; Bouman, W.P.; Arcelus, J.; Savvidou, L.G.; et al. Sex addiction and gambling disorder: Similarities and differences. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafka, M.P. Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010, 39, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.S.; Krueger, R.B. Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of hypersexuality. J. Sex. Res. 2010, 47, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, R.C. Additional challenges and issues in classifying compulsive sexual behavior as an addiction. Addiction 2016, 111, 2111–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gola, M.; Lewczuk, K.; Skorko, M. What Matters: Quantity or Quality of Pornography Use? Psychological and Behavioral Factors of Seeking Treatment for Problematic Pornography Use. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, R.C.; Carpenter, B.N.; Hook, J.N.; Garos, S.; Manning, J.C.; Gilliland, R.; Cooper, E.B.; McKittrick, H.; Davtian, M.; Fong, T. Report of findings in a DSM-5 field trial for hypersexual disorder. J. Sex. Med. 2012, 9, 2868–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bancroft, J.; Vukadinovic, Z. Sexual addiction, sexual compulsivity, sexual impulsivity, or what? Toward a theoretical model. J. Sex. Res. 2004, 41, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancroft, J. Sexual behavior that is “out of control”: A theoretical conceptual approach. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 31, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, D.J.; Black, D.W.; Pienaar, W. Sexual disorders not otherwise specified: Compulsive, addictive, or impulsive? CNS Spectr. 2000, 5, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafka, M.P.; Prentky, R.A. Compulsive sexual behavior characteristics. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafka, M.P. What happened to hypersexual disorder? Arch. Sex. Behav. 2014, 43, 1259–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.B. Diagnosis of hypersexual or compulsive sexual behavior can be made using ICD-10 and DSM-5 despite rejection of this diagnosis by the American Psychiatric Association. Addiction 2016, 111, 2110–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.; Kafka, M. Controversies about Hypersexual Disorder and the DSM-5. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 2014, 6, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kor, A.; Fogel, Y.; Reid, R.C.; Potenza, M.N. Should Hypersexual Disorder be Classified as an Addiction? Sex. Addict. Compuls. 2013, 20, 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E. Is Your Patient Suffering from Compulsive Sexual Behavior? Psychiatr. Ann. 1992, 22, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.; Raymond, N.; McBean, A. Assessment and treatment of compulsive sexual behavior. Minn. Med. 2003, 86, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kafka, M.P.; Prentky, R. A comparative study of nonparaphilic sexual addictions and paraphilias in men. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1992, 53, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Derbyshire, K.L.; Grant, J.E. Compulsive sexual behavior: A review of the literature. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafka, M.P.; Hennen, J. The paraphilia-related disorders: An empirical investigation of nonparaphilic hypersexuality disorders in outpatient males. J. Sex. Marital Ther. 1999, 25, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, D.J. Classifying hypersexual disorders: Compulsive, impulsive, and addictive models. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 31, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochner, C.; Stein, D.J. Does work on obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders contribute to understanding the heterogeneity of obsessive-compulsive disorder? Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 30, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.J.; Kinder, B.N. The mislabeling of sexual impulsivity. J. Sex. Marital Ther. 1987, 13, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, D.J.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Fineberg, N. An A-B-C model of habit disorders: Hair-pulling, skin-picking, and other stereotypic conditions. CNS Spectr. 2006, 11, 824–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, A. Addictive Disorders: An Integrated Approach: Part One-An Integrated Understanding. J. Minist. Addict. Recover. 1995, 2, 33–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnes, P.J. Sexual addiction and compulsion: Recognition, treatment, and recovery. CNS Spectr. 2000, 5, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potenza, M.N. The neurobiology of pathological gambling and drug addiction: An overview and new findings. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 3181–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orzack, M.H.; Ross, C.J. Should Virtual Sex Be Treated Like Other Sex Addictions? Sex. Addict. Compuls. 2000, 7, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzman, S.T.; Butler, M.H. Wives’ Experience of Husbands’ Pornography Use and Concomitant Deception as an Attachment Threat in the Adult Pair-Bond Relationship. Sex. Addict. Compuls. 2009, 16, 210–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, K.P.; O’Connor, S.; Carnes, P. Chapter 9—Sex Addiction: An Overview∗. In Behavioral Addictions; Rosenberg, K.P., Feder, L.C., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 215–236. ISBN 978-0-12-407724-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.W.; Voon, V.; Kor, A.; Potenza, M.N. Searching for clarity in muddy water: Future considerations for classifying compulsive sexual behavior as an addiction. Addiction 2016, 111, 2113–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.E.; Chamberlain, S.R. Expanding the definition of addiction: DSM-5 vs. ICD-11. CNS Spectr. 2016, 21, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wéry, A.; Karila, L.; De Sutter, P.; Billieux, J. Conceptualisation, évaluation et traitement de la dépendance cybersexuelle: Une revue de la littérature. Can. Psychol. 2014, 55, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, M.P.; Dew, B.J. Online Experiences of Sexually Compulsive Men Who Have Sex with Men. Sex. Addict. Compuls. 2003, 10, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, A.; Caretti, V. Psychic retreats or psychic pits? Unbearable states of mind and technological addiction. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2010, 27, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D. Internet sex addiction: A review of empirical research. Addict. Res. Theory 2012, 20, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Cremades, F.; Simonelli, C.; Montejo, A.L. Sexual disorders beyond DSM-5: The unfinished affaire. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.W.; Krueger, R.B.; Briken, P.; First, M.B.; Stein, D.J.; Kaplan, M.S.; Voon, V.; Abdo, C.H.N.; Grant, J.E.; Atalla, E.; et al. Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder in the ICD-11. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, S.E.; Andrews, G.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Gaebel, W.; Goldberg, D.; Gureje, O.; Jablensky, A.; Khoury, B.; Lovell, A.; Medina Mora, M.E.; et al. A conceptual framework for the revision of the ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. World Psychiatry 2011, 10, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.Y.; Wilson, G.; Berger, J.; Christman, M.; Reina, B.; Bishop, F.; Klam, W.P.; Doan, A.P. Is Internet Pornography Causing Sexual Dysfunctions? A Review with Clinical Reports. Behav. Sci. (Basel) 2016, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, G. Eliminate Chronic Internet Pornography Use to Reveal Its Effects. Addicta Turkish J. Addict. 2016, 3, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais-Lecours, S.; Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P.; Sabourin, S.; Godbout, N. Cyberpornography: Time Use, Perceived Addiction, Sexual Functioning, and Sexual Satisfaction. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albright, J.M. Sex in America online: An exploration of sex, marital status, and sexual identity in internet sex seeking and its impacts. J. Sex. Res. 2008, 45, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minarcik, J.; Wetterneck, C.T.; Short, M.B. The effects of sexually explicit material use on romantic relationship dynamics. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyle, T.M.; Bridges, A.J. Perceptions of relationship satisfaction and addictive behavior: Comparing pornography and marijuana use. J. Behav. Addict. 2012, 1, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, I.M.; Hamilton, L.D. Male-Centric and Female-Centric Pornography Consumption: Relationship With Sex Life and Attitudes in Young Adults. J. Sex. Marital Ther. 2018, 44, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starcevic, V.; Khazaal, Y. Relationships between Behavioural Addictions and Psychiatric Disorders: What Is Known and What Is Yet to Be Learned? Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, M.; Rath, P. Effect of internet on the psychosomatic health of adolescent school children in Rourkela—A cross-sectional study. Indian J. Child Health 2017, 4, 289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, A.; Cash, H.; Hurdiss, S.; Bishop, F.; Klam, W.P.; Doan, A.P. Case Report: Internet Gaming Disorder Associated With Pornography Use. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale, L.; Coyne, S.M. Video game addiction in emerging adulthood: Cross-sectional evidence of pathology in video game addicts as compared to matched healthy controls. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 225, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubbs, J.B.; Wilt, J.A.; Exline, J.J.; Pargament, K.I. Predicting pornography use over time: Does self-reported “addiction” matter? Addict. Behav. 2018, 82, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas, D.; Pont-Sunyer, C.; Tolosa, E. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2012, 18, S80–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, M.; Bonuccelli, U. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: The role of personality and cognitive status. J. Neurol. 2012, 259, 2269–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, D.L. Pornography addiction—A supranormal stimulus considered in the context of neuroplasticity. Socioaffect. Neurosci. Psychol. 2013, 3, 20767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Koob, G.F.; McLellan, A.T. Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderschuren, L.J.M.J.; Pierce, R.C. Sensitization processes in drug addiction. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2010, 3, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.-J.; Fowler, J.S.; Tomasi, D.; Telang, F.; Baler, R. Addiction: Decreased reward sensitivity and increased expectation sensitivity conspire to overwhelm the brain’s control circuit. Bioessays 2010, 32, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.Z.; Volkow, N.D. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: Neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 652–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F. Addiction is a Reward Deficit and Stress Surfeit Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2013, 4, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechelmans, D.J.; Irvine, M.; Banca, P.; Porter, L.; Mitchell, S.; Mole, T.B.; Lapa, T.R.; Harrison, N.A.; Potenza, M.N.; Voon, V. Enhanced attentional bias towards sexually explicit cues in individuals with and without compulsive sexual behaviours. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seok, J.-W.; Sohn, J.-H. Neural Substrates of Sexual Desire in Individuals with Problematic Hypersexual Behavior. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamann, S. Sex differences in the responses of the human amygdala. Neuroscientist 2005, 11, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klucken, T.; Wehrum-Osinsky, S.; Schweckendiek, J.; Kruse, O.; Stark, R. Altered Appetitive Conditioning and Neural Connectivity in Subjects with Compulsive Sexual Behavior. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sescousse, G.; Caldú, X.; Segura, B.; Dreher, J.-C. Processing of primary and secondary rewards: A quantitative meta-analysis and review of human functional neuroimaging studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, V.R.; Staley, C.; Fong, T.; Prause, N. Sexual desire, not hypersexuality, is related to neurophysiological responses elicited by sexual images. Socioaffect. Neurosci. Psychol. 2013, 3, 20770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, D.L. ‘High desire’, or ‘merely’ an addiction? A response to Steele et al. Socioaffect. Neurosci. Psychol. 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prause, N.; Steele, V.R.; Staley, C.; Sabatinelli, D.; Hajcak, G. Modulation of late positive potentials by sexual images in problem users and controls inconsistent with “porn addiction”. Biol. Psychol. 2015, 109, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laier, C.; Pekal, J.; Brand, M. Cybersex addiction in heterosexual female users of internet pornography can be explained by gratification hypothesis. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laier, C.; Pekal, J.; Brand, M. Sexual Excitability and Dysfunctional Coping Determine Cybersex Addiction in Homosexual Males. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, R.; Klucken, T. Neuroscientific Approaches to (Online) Pornography Addiction. In Internet Addiction; Studies in Neuroscience, Psychology and Behavioral Economics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 109–124. ISBN 978-3-319-46275-2. [Google Scholar]

- Albery, I.P.; Lowry, J.; Frings, D.; Johnson, H.L.; Hogan, C.; Moss, A.C. Exploring the Relationship between Sexual Compulsivity and Attentional Bias to Sex-Related Words in a Cohort of Sexually Active Individuals. Eur. Addict. Res. 2017, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunaharan, S.; Halpin, S.; Sitharthan, T.; Bosshard, S.; Walla, P. Conscious and Non-Conscious Measures of Emotion: Do They Vary with Frequency of Pornography Use? Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S.; Gallinat, J. Brain Structure and Functional Connectivity Associated with Pornography Consumption: The Brain on Porn. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banca, P.; Morris, L.S.; Mitchell, S.; Harrison, N.A.; Potenza, M.N.; Voon, V. Novelty, conditioning and attentional bias to sexual rewards. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 72, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banca, P.; Harrison, N.A.; Voon, V. Compulsivity Across the Pathological Misuse of Drug and Non-Drug Rewards. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gola, M.; Wordecha, M.; Sescousse, G.; Lew-Starowicz, M.; Kossowski, B.; Wypych, M.; Makeig, S.; Potenza, M.N.; Marchewka, A. Can Pornography be Addictive? An fMRI Study of Men Seeking Treatment for Problematic Pornography Use. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 2021–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.; Morris, L.S.; Kvamme, T.L.; Hall, P.; Birchard, T.; Voon, V. Compulsive sexual behavior: Prefrontal and limbic volume and interactions. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, M.; Snagowski, J.; Laier, C.; Maderwald, S. Ventral striatum activity when watching preferred pornographic pictures is correlated with symptoms of Internet pornography addiction. Neuroimage 2016, 129, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balodis, I.M.; Potenza, M.N. Anticipatory reward processing in addicted populations: A focus on the monetary incentive delay task. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 77, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seok, J.-W.; Sohn, J.-H. Gray matter deficits and altered resting-state connectivity in the superior temporal gyrus among individuals with problematic hypersexual behavior. Brain Res. 2018, 1684, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taki, Y.; Kinomura, S.; Sato, K.; Goto, R.; Inoue, K.; Okada, K.; Ono, S.; Kawashima, R.; Fukuda, H. Both global gray matter volume and regional gray matter volume negatively correlate with lifetime alcohol intake in non-alcohol-dependent Japanese men: A volumetric analysis and a voxel-based morphometry. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006, 30, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzittofis, A.; Arver, S.; Öberg, K.; Hallberg, J.; Nordström, P.; Jokinen, J. HPA axis dysregulation in men with hypersexual disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 63, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokinen, J.; Boström, A.E.; Chatzittofis, A.; Ciuculete, D.M.; Öberg, K.G.; Flanagan, J.N.; Arver, S.; Schiöth, H.B. Methylation of HPA axis related genes in men with hypersexual disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 80, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, K.; Werner, T.; Carnes, S.; Carnes, P.; Bowirrat, A.; Giordano, J.; Oscar-Berman, M.; Gold, M. Sex, drugs, and rock “n” roll: Hypothesizing common mesolimbic activation as a function of reward gene polymorphisms. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2012, 44, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokinen, J.; Chatzittofis, A.; Nordstrom, P.; Arver, S. The role of neuroinflammation in the pathophysiology of hypersexual disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 71, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.C.; Karim, R.; McCrory, E.; Carpenter, B.N. Self-reported differences on measures of executive function and hypersexual behavior in a patient and community sample of men. Int. J. Neurosci. 2010, 120, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppink, E.; Chamberlain, S.; Redden, S.; Grant, J. Problematic sexual behavior in young adults: Associations across clinical, behavioral, and neurocognitive variables. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 246, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamaruddin, N.; Rahman, A.W.A.; Handiyani, D. Pornography Addiction Detection based on Neurophysiological Computational Approach. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2018, 10, 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, M.; Laier, C.; Pawlikowski, M.; Schächtle, U.; Schöler, T.; Altstötter-Gleich, C. Watching pornographic pictures on the Internet: Role of sexual arousal ratings and psychological-psychiatric symptoms for using Internet sex sites excessively. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laier, C.; Schulte, F.P.; Brand, M. Pornographic picture processing interferes with working memory performance. J. Sex. Res. 2013, 50, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, M.H.; Raymond, N.; Mueller, B.A.; Lloyd, M.; Lim, K.O. Preliminary investigation of the impulsive and neuroanatomical characteristics of compulsive sexual behavior. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 174, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Chiou, W.-B. Exposure to Sexual Stimuli Induces Greater Discounting Leading to Increased Involvement in Cyber Delinquency Among Men. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 21, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, B.; Fuentes, D.; Tavares, H.; Abdo, C.H.N.; Scanavino, M.d.T. Executive Functioning of Sexually Compulsive and Non-Sexually Compulsive Men Before and After Watching an Erotic Video. J. Sex. Med. 2017, 14, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negash, S.; Sheppard, N.V.N.; Lambert, N.M.; Fincham, F.D. Trading Later Rewards for Current Pleasure: Pornography Consumption and Delay Discounting. J. Sex. Res. 2016, 53, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirianni, J.M.; Vishwanath, A. Problematic Online Pornography Use: A Media Attendance Perspective. J. Sex. Res. 2016, 53, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laier, C.; Pawlikowski, M.; Pekal, J.; Schulte, F.P.; Brand, M. Cybersex addiction: Experienced sexual arousal when watching pornography and not real-life sexual contacts makes the difference. J. Behav. Addict. 2013, 2, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, M.; Young, K.S.; Laier, C. Prefrontal control and internet addiction: A theoretical model and review of neuropsychological and neuroimaging findings. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snagowski, J.; Wegmann, E.; Pekal, J.; Laier, C.; Brand, M. Implicit associations in cybersex addiction: Adaption of an Implicit Association Test with pornographic pictures. Addict. Behav. 2015, 49, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snagowski, J.; Laier, C.; Duka, T.; Brand, M. Subjective Craving for Pornography and Associative Learning Predict Tendencies Towards Cybersex Addiction in a Sample of Regular Cybersex Users. Sex. Addict. Compuls. 2016, 23, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, M.T.; Cantor, J.M.; Lykins, A.D. An Online Assessment of Personality, Psychological, and Sexuality Trait Variables Associated with Self-Reported Hypersexual Behavior. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 46, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, J.T.; Kelly, B.C.; Bimbi, D.S.; Muench, F.; Morgenstern, J. Accounting for the social triggers of sexual compulsivity. J. Addict. Dis. 2007, 26, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laier, C.; Brand, M. Mood changes after watching pornography on the Internet are linked to tendencies towards Internet-pornography-viewing disorder. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2017, 5, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laier, C.; Brand, M. Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Considerations on Factors Contributing to Cybersex Addiction from a Cognitive-Behavioral View. Sex. Addict. Compuls. 2014, 21, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antons, S.; Brand, M. Trait and state impulsivity in males with tendency towards Internet-pornography-use disorder. Addict. Behav. 2018, 79, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, V.; Parmar, R. Dirty habits? Online pornography use, personality, obsessionality, and compulsivity. J. Sex. Marital Ther. 2013, 39, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, M.; Štulhofer, A.; Waldorp, L.; Jurin, T. A Network Approach to Hypersexuality: Insights and Clinical Implications. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snagowski, J.; Brand, M. Symptoms of cybersex addiction can be linked to both approaching and avoiding pornographic stimuli: Results from an analog sample of regular cybersex users. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiebener, J.; Laier, C.; Brand, M. Getting stuck with pornography? Overuse or neglect of cybersex cues in a multitasking situation is related to symptoms of cybersex addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brem, M.J.; Shorey, R.C.; Anderson, S.; Stuart, G.L. Depression, anxiety, and compulsive sexual behaviour among men in residential treatment for substance use disorders: The role of experiential avoidance. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 24, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnes, P. Sexual addiction screening test. Tenn. Nurse 1991, 54, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery-Graham, S. Conceptualization and Assessment of Hypersexual Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sex. Med. Rev. 2017, 5, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, M.H.; Coleman, E.; Center, B.A.; Ross, M.; Rosser, B.R.S. The compulsive sexual behavior inventory: Psychometric properties. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2007, 36, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, M.H.; Raymond, N.; Coleman, E.; Swinburne Romine, R. Investigating Clinically and Scientifically Useful Cut Points on the Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory. J. Sex. Med. 2017, 14, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberg, K.G.; Hallberg, J.; Kaldo, V.; Dhejne, C.; Arver, S. Hypersexual Disorder According to the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory in Help-Seeking Swedish Men and Women With Self-Identified Hypersexual Behavior. Sex. Med. 2017, 5, e229–e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmonico, D.; Miller, J. The Internet Sex Screening Test: A comparison of sexual compulsives versus non-sexual compulsives. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2003, 18, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester Arnal, R.; Gil Llario, M.D.; Gómez Martínez, S.; Gil Juliá, B. Psychometric properties of an instrument for assessing cyber-sex addiction. Psicothema 2010, 22, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel, M.E.; Giralt, S.; Wölfling, K.; Stöbel-Richter, Y.; Subic-Wrana, C.; Reiner, I.; Tibubos, A.N.; Brähler, E. Prevalence and determinants of online-sex use in the German population. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kor, A.; Zilcha-Mano, S.; Fogel, Y.A.; Mikulincer, M.; Reid, R.C.; Potenza, M.N. Psychometric development of the Problematic Pornography Use Scale. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wéry, A.; Burnay, J.; Karila, L.; Billieux, J. The Short French Internet Addiction Test Adapted to Online Sexual Activities: Validation and Links With Online Sexual Preferences and Addiction Symptoms. J. Sex. Res. 2016, 53, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubbs, J.B.; Volk, F.; Exline, J.J.; Pargament, K.I. Internet pornography use: Perceived addiction, psychological distress, and the validation of a brief measure. J. Sex. Marital Ther. 2015, 41, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, D.P.; Tee, E.Y.J.; Fernandez, E.F. Do Cyber Pornography Use Inventory-9 Scores Reflect Actual Compulsivity in Internet Pornography Use? Exploring the Role of Abstinence Effort. Sex. Addict. Compuls. 2017, 24, 156–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bőthe, B.; Tóth-Király, I.; Zsila, Á.; Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z.; Orosz, G. The Development of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS). J. Sex. Res. 2018, 55, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, M. A “Components” Model of Addiction within a Biopsychosocial Framework. J. Subst. Use 2009, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.C.; Li, D.S.; Gilliland, R.; Stein, J.A.; Fong, T. Reliability, validity, and psychometric development of the pornography consumption inventory in a sample of hypersexual men. J. Sex. Marital Ther. 2011, 37, 359–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltieri, D.A.; Aguiar, A.S.J.; de Oliveira, V.H.; de Souza Gatti, A.L.; de Souza Aranha E Silva, R.A. Validation of the Pornography Consumption Inventory in a Sample of Male Brazilian University Students. J. Sex. Marital Ther. 2015, 41, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.W.; Simon Rosser, B.R.; Erickson, D.J. A Brief Scale to Measure Problematic Sexually Explicit Media Consumption: Psychometric Properties of the Compulsive Pornography Consumption (CPC) Scale among Men who have Sex with Men. Sex. Addict. Compuls. 2014, 21, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, S.; Rosenberg, H. The pornography craving questionnaire: Psychometric properties. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2014, 43, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, S.W.; Rosenberg, H.; Tompsett, C.J. Assessment of self-efficacy to employ self-initiated pornography use-reduction strategies. Addict. Behav. 2015, 40, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, S.W.; Rosenberg, H.; Martino, S.; Nich, C.; Potenza, M.N. The development and initial evaluation of the Pornography-Use Avoidance Self-Efficacy Scale. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sniewski, L.; Farvid, P.; Carter, P. The assessment and treatment of adult heterosexual men with self-perceived problematic pornography use: A review. Addict. Behav. 2018, 77, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gola, M.; Potenza, M.N. Paroxetine Treatment of Problematic Pornography Use: A Case Series. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, T.W. Understanding and managing compulsive sexual behaviors. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2006, 3, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Aboujaoude, E.; Salame, W.O. Naltrexone: A Pan-Addiction Treatment? CNS Drugs 2016, 30, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, N.C.; Grant, J.E.; Coleman, E. Augmentation with naltrexone to treat compulsive sexual behavior: A case series. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 22, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.W.; Meshberg-Cohen, S.; Martino, S.; Quinones, L.J.; Potenza, M.N. Treatment of Compulsive Pornography Use with Naltrexone: A Case Report. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 1260–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostwick, J.M.; Bucci, J.A. Internet sex addiction treated with naltrexone. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2008, 83, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, M.; Moura, A.R.; Oliveira-Maia, A.J. Compulsive Sexual Behaviors Treated With Naltrexone Monotherapy. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capurso, N.A. Naltrexone for the treatment of comorbid tobacco and pornography addiction. Am. J. Addict. 2017, 26, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Short, M.B.; Wetterneck, C.T.; Bistricky, S.L.; Shutter, T.; Chase, T.E. Clinicians’ Beliefs, Observations, and Treatment Effectiveness Regarding Clients’ Sexual Addiction and Internet Pornography Use. Commun. Ment. Health J. 2016, 52, 1070–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orzack, M.H.; Voluse, A.C.; Wolf, D.; Hennen, J. An ongoing study of group treatment for men involved in problematic Internet-enabled sexual behavior. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.S. Cognitive behavior therapy with Internet addicts: Treatment outcomes and implications. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, S.A.; Ruchty, J.; Hull, T.; Hyde, R. A Preliminary Study of an Online Psychoeducational Program for Hypersexuality. Sex. Addict. Compuls. 2010, 17, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, J.M.; Twohig, M.P. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Problematic Internet Pornography Use: A Randomized Trial. Behav. Ther. 2016, 47, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twohig, M.P.; Crosby, J.M. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for problematic internet pornography viewing. Behav. Ther. 2010, 41, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]