Comments: Review in a urology journal describes excessive porn use as a cause of both erectile dysfunction and delayed ejaculation. Relevant excerpts:

Common factors that can cause secondary erectile dysfunction include recent loss or failures, ageing, illness or surgery, alcohol and substance abuse, relationship problems or infidelity, depression, premature ejaculation (often comorbid with erectile dysfunction), and sexually compulsive and addictive behaviours that can lead to ‘porn‐induced’ erectile dysfunction. In regards to this latter category, a 2016 study6 of 1492 adolescents in their final year of high school found that 77.9% of internet users admitted to the consumption of pornographic material. Of this figure, 59% of boys accessing these sites always perceived their consumption of pornography to be stimulating, 21.9% defined their behaviour as habitual and 10% reported that it reduced levels of sexual interest towards potential real‐life partners. Nineteen per cent of overall pornography users reported an abnormal sexual response in real‐life situations, which increased to 25.1% among regular consumers.

A 2016 review found that factors that once explained men’s sexual dysfunction appear to be insufficient to account for the significant rise in sexual dysfunction during partnered sex in men under 40 years of age.7 The review explores alterations to the brain’s motivational system when pornography is excessively used, looking at the evidence that unique properties relating to internet pornography – for example, limitless novelty and the potential for easy estretion to more extreme material – may condition individuals in terms of sexual arousal. This can result in real‐life partners no longer meeting sexual expectations and the subsequent decline in adequate arousal for partnered, real‐life sexual activity.

—————-

Delayed ejaculation is characterised as the inability to ejaculate during sexual activity, specifically after 25–30 minutes of continuous sexual stimulation….

The common factors that predispose some men to developing this disorder are: aging, which will inevitably produce sexual changes, including delay of ejaculation; IMS (idiosyncratic masturbation style), when men masturbate with a speed and pressure that their partner may not be able to duplicate; fear of impregnating a woman; excessive exposure to pornography that results in stimuli overexposure and desensitisation; sexual trauma and/or cultural and religious prohibitions.

Trends in Urology & Men’s Health

Emma Mathews. First published: 04 June 2020

https://doi.org/10.1002/tre.748

Abstract

Psychosexual therapy can be a valuable addition to the management of male sexual problems. Encouraging men to consult on such issues is another matter, however.

Main sexual disorders in men

The American Psychiatric Association (APA)2 outline current male sexual dysfunctions as: erectile dysfunction; premature ejaculation; delayed ejaculation; male hypoactive sexual desire disorder; substance/medication‐induced sexual dysfunction; other specified sexual dysfunctions; and unspecified sexual dysfunction. To meet criteria for the diagnosis of these conditions the APA state that a patient should experience the dysfunction 75–100% of the time, with a minimum duration of approximately six months, and the dysfunction must be deemed to cause significant distress. The dysfunction can be classed as mild, moderate or severe.

Erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation appear to be the most commonly reported male sexual problems. A 2005 worldwide study found that the prevalence of premature ejaculation was 30% in men aged between 40–80 years.3 Erectile dysfunction has also been found to increase in prevalence with age, with 6% prevalence in men under 49 years old, 16% between 50–59 years old, 32% between the ages of 60–69 years, and 44% of men aged 70–79 years.4 Other male sexual dysfunctions tend to affect less than 10% of men of all ages.1

Screening for organic and psychological causes

Sexual problems can have organic and psychological causes; however, many men prefer to believe their sexual problem has an organic cause as this is often deemed easier to treat with medication. Consequently, a GP is usually a good starting point for men with sexual problems to seek advice and appropriate tests to confirm or exclude organic causes that may underlie or be contributing to the problem. Table 1 provides information on the recommended screening tests.

| Pre‐referral screening guide | |

|---|---|

| Erectile dysfunction |

|

| Premature ejaculation |

|

| Delayed ejaculation |

|

| Hypoactive sexual desire disorder |

|

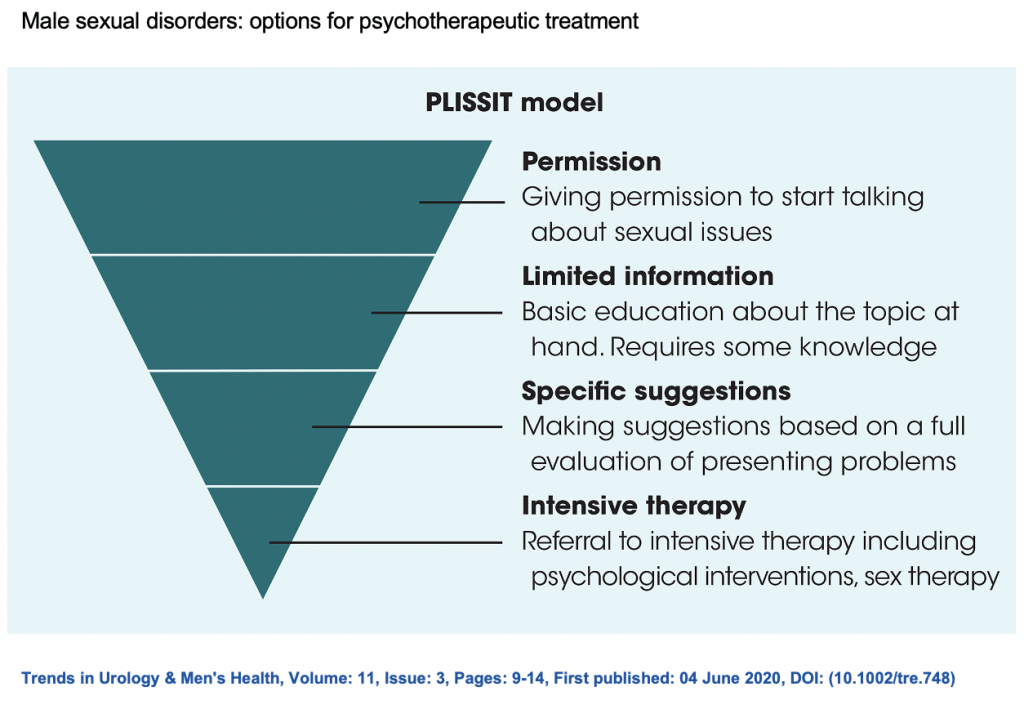

Unfortunately, both patients and healthcare professionals may be reluctant to address sexual concerns during appointments due to time limitations or a lack of knowledge on the part of the professional, or shame and embarrassment on the part of the patient. Therefore, it is important for healthcare professionals to have the necessary skills to enquire about sexual problems, give basic advice and refer appropriately. The PLISSIT (Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, Intensive Therapy) model5 details a method for appropriately introducing sex into a clinical conversation, with the rationale being to reduce patients’ concerns about bringing up sexual problems themselves (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

These are four levels of intervention that healthcare professionals in all specialties can use:

Permission – make the space for a patient to bring up sexual problems by asking open‐ended questions;

Limited information – offer targeted information, including potential causes of the problem;

Specific suggestions – different diagnoses may be suggested, with ideas of how to address the problem;

Intensive therapy – referral to a specialist (for example, a psychosexual therapist) to provide more specific support and interventions.

Common psychosocial factors

Erectile dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction is characterised by a recurrent inability to achieve or maintain an adequate erection during partnered sexual activities. This can be primary (ie has occurred since the onset of partnered sexual activity), or secondary (ie has occurred after a period of normal sexual function).2

There are varying psychological factors that can predispose some men to develop primary erectile dysfunction. These include self‐esteem invested in sexual performance, a lack of comfort with sexuality, traumatic or difficult first sexual experience and religious taboos.

Common factors that can cause secondary erectile dysfunction include recent loss or failures, ageing, illness or surgery, alcohol and substance abuse, relationship problems or infidelity, depression, premature ejaculation (often comorbid with erectile dysfunction), and sexually compulsive and addictive behaviours that can lead to ‘porn‐induced’ erectile dysfunction. In regards to this latter category, a 2016 study6 of 1492 adolescents in their final year of high school found that 77.9% of internet users admitted to the consumption of pornographic material. Of this figure, 59% of boys accessing these sites always perceived their consumption of pornography to be stimulating, 21.9% defined their behaviour as habitual and 10% reported that it reduced levels of sexual interest towards potential real‐life partners. Nineteen per cent of overall pornography users reported an abnormal sexual response in real‐life situations, which increased to 25.1% among regular consumers.

A 2016 review found that factors that once explained men’s sexual dysfunction appear to be insufficient to account for the significant rise in sexual dysfunction during partnered sex in men under 40 years of age.7 The review explores alterations to the brain’s motivational system when pornography is excessively used, looking at the evidence that unique properties relating to internet pornography – for example, limitless novelty and the potential for easy estretion to more extreme material – may condition individuals in terms of sexual arousal. This can result in real‐life partners no longer meeting sexual expectations and the subsequent decline in adequate arousal for partnered, real‐life sexual activity.

Premature ejaculation

Premature ejaculation is characterised as consistently ejaculating within one minute or less of penetration. Some men will also consistently ejaculate during foreplay before penetration is attempted.

There are specifiers for this disorder. For example, it can be lifelong, experienced since the first intercourse attempt; acquired, appearing after a period of sufficient orgasmic latency; generalised, occurring with different partners and situations; or situational, when the problem only occurs with a specific partner or situation.

The severity of the disorder can also be further specified. It can be mild, in which ejaculation occurs 30–60 seconds after penetration is attempted; moderate, when ejaculation occurs 15–30 seconds after penetration; or severe, in which ejaculation occurs prior to penetration, upon penetration, or less than 15 seconds after penetration.2

The common factors that predispose some men to developing premature ejaculation include religious factors, restrictive upbringing, dominating or disapproving parents (leading to an individual setting themselves impossible goals), fear of discovery during early sexual experiences (partnered and masturbation), a perceived need to ‘be quick’, and anxiety disorders.

Delayed ejaculation

Delayed ejaculation is characterised as the inability to ejaculate during sexual activity, specifically after 25–30 minutes of continuous sexual stimulation.

The specifiers for this disorder include it being: lifelong, commencing at the onset of sexual activity; acquired, starting after a period of normal sexual function; generalised, when ejaculation is delayed or not possible in either solitary or partnered sexual activity; or situational, when a man can ejaculate while masturbating but not with a partner or during specific sex acts (for example, ejaculation during oral stimulation but not vaginal or anal intercourse).2

The common factors that predispose some men to developing this disorder are: aging, which will inevitably produce sexual changes, including delay of ejaculation; IMS (idiosyncratic masturbation style), when men masturbate with a speed and pressure that their partner may not be able to duplicate; fear of impregnating a woman; excessive exposure to pornography that results in stimuli overexposure and desensitisation; sexual trauma and/or cultural and religious prohibitions.

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder is characterised as low desire for sex and absent sexual thoughts or fantasies.2 Common factors that precipitate hypoactive sexual desire disorder include: sexual trauma; relationship problems (anger, hostility, poor communication, anxiety about relationship security); psychological disorders (depression, anxiety, panic); low physiological arousal; stress and exhaustion.

What to expect during psychosexual therapy?

Coming to see a psychosexual therapist can be a daunting experience and some will express a preference to see a male or female therapist.

Psychosexual therapy involves gradually changing behaviours that maintain sexual difficulties. If a patient is in an intimate relationship it is usually preferable that they attend with their partner, as it is often helpful to understand how both parties may be contributing to the problem. However, this is not always necessary, depending on the problem and the individual circumstances.

The initial assessment is used to ascertain a basic idea about the nature of the problem. The patient will be asked questions about when the problem started, medical and surgical history (including mental health), and some questions about the relationship in general (if they are in an intimate relationship). The patient will then be given details about what therapy will involve, time commitments and their motivation to engage will also be assessed.

The patient will then be offered further assessment to help the therapist ‘formulate’ the problem. For this purpose, the patient will be asked questions about the dynamics in their current relationship, what happens when they are intimate with their partner, details of previous intimate relationships, and messages they may have received about sex and masculinity (along with details about family dynamics) during their childhood. The therapist will be looking for possible attachment issues developed during childhood and replayed during adult relationships, psychological trauma and also systemic influences. This is all to gain a greater understanding of how the patient relates to others, be that in a couple, family or community.

The psychological assessment is extremely thorough. If a patient is currently in an intimate relationship their therapist will also ask to see the partner alone to ask the same questions to try to gain a complete understanding of the problem. The therapist will discuss the formulation with the patient and partner, provide education on sexual response cycles and on the specifics of the presenting problem.

Putting the problem into perspective

With all sexual disorders there are common elements to treatment. Firstly, it is important to help redefine a patient’s perspective so that they do not define themselves only in terms of the sexual problem. In order to do this, it is helpful to facilitate a discussion around other aspects of relationships that are important; for example, trust, respect, having fun, affection, good communication, and non‐sexual and sexual intimacy.

When discussing sexual intimacy, this can be further broken down to allow patients to see sex as something that is dynamic and creative. In particular, try to remove the patient’s focus on penetrative intercourse, including their need to last for a certain amount of time or to reach climax. Patients often attend sessions with preconceived ideas around what constitutes ‘normal’ and what ‘everyone else’ is doing in relation to sex. Part of sexual therapy is therefore to normalise the problem, providing data on its prevalence and how other patients have had similar concerns and benefited from treatment.

Between‐session homework tasks

Psychosexual therapy usually involves asking patients to complete ‘homework tasks’ between sessions and report back on their experienced thoughts, emotions, physical sensations and behaviours. This allows therapists to pace therapy appropriately and troubleshoot any difficulties that occur.

One of the main homework tasks if a patient has a partner is sensate focus. This method was first introduced by Masters and Johnson8 and allows patients to be exposed to intimacy in a graded way that lets them learn to be mindful (without judgement) during intimacy, reduce anxiety and regain confidence in their sexual performance. The first rule is a sex ban. The couple both need to agree to this when starting the homework tasks, which often start with touching each other in a non‐sexual way (for example, spending time touching their partner’s naked body with the exclusion of sexual areas such as the genitals and breasts). The rationale of this approach is to expose the patient to intimate physical contact without fear that the patient will need to ‘perform’. As the therapy develops, the tasks introduce touch that becomes more intimate and sexual. Depending on the specific problem, a patient may also be asked to complete some masturbatory tasks alone to gain confidence and control.

Patients who present for treatment and are not currently in a relationship can be more problematic to treat, especially if the problem only occurs during partnered sexual activity. While these patients can benefit from the masturbatory exercises, it is not possible to anticipate how they may react if they do start a sexual relationship. In this instance, using more cognitive‐focused techniques during therapy sessions may be appropriate to address what could be maintaining the problem, such as catastrophic thought processes, overvaluation of the importance of penetrative sex in a relationship and building general self‐esteem. These techniques require therapists to elicit patients’ negative core beliefs about themselves and then try to shift their self‐perceptions to build more positive or realistic self‐beliefs.

A German study9 looked at changes in sexual function following cognitive behavioural therapy for other psychological disorders –generalised anxiety or depression, for example. The study found that many patients whose symptoms remitted for the primary problem also had improvement in sexual function, even when the therapy was not directly focused on the sexual problem. Remission of the sexual disorder was seen as a positive side‐effect of treating the presenting psychological disorder; however, 45% had no improvement in sexual function. The authors concluded that the recognition of sexual disorders should be integrated into case formulations of patients presenting with other psychological disorders.

If psychological trauma has been identified to be a significant precipitant of the problem, then trauma‐focused therapy may also be appropriate. In such cases, use trauma‐focused cognitive behavioural therapy, or eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing, as recommended by NICE guidance.10

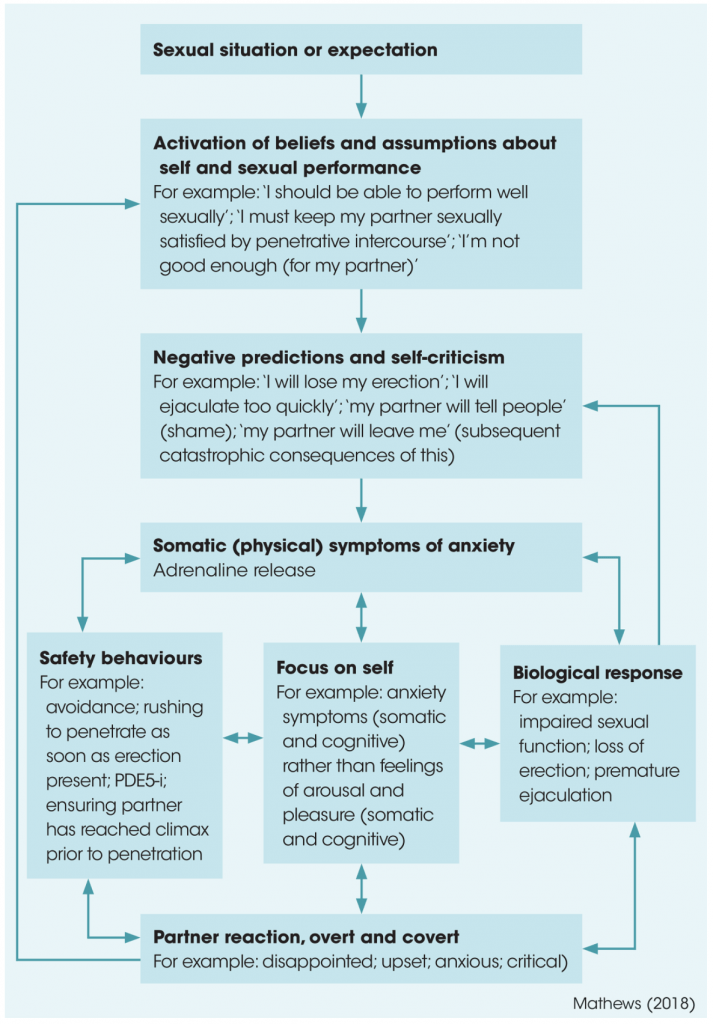

In all patients an understanding of the factors that can create and maintain performance‐related problems can be helpful (see Figure 2). It can also be useful for partners of men with sexual problems to receive this education to help them to understand how their reactions, both overt and covert, may contribute to the maintenance of the sexual problem. It can be reassuring for the partner (and therefore the patient) to find out that male sexual dysfunction is often not a reflection on the partner but more an anxiety disorder.

Figure 2

Case study: erectile dysfunction

John (not the patient’s real name), aged 35 years, had been married to his wife for ten years and had experienced problems maintaining an adequate erection during penetrative intercourse throughout their relationship. No organic reason for the problem had been identified following routine tests by the GP. During assessment, it was identified that John had perfectionistic tendencies and beliefs about not being ‘good enough’ for his wife. His wife had subsequently developed a belief that John maybe did not find her attractive, which made John more anxious during sex to prove this was not the case.

As a result, sex was frequently avoided and both John and his wife became very anxious during intimacy. If John achieved an erection he tried to penetrate as soon as it occurred. His wife, while trying to be understanding, would sometimes become frustrated with him. If they tried to change position during penetrative sex, he would lose his erection. They therefore adopted a ‘safe’ position for penetrative sex that they avoided changing. Sex was not enjoyable for either partner as it had become an anxiety‐provoking experience.

There were also issues in the relationship in terms of making time for intimacy. Both were busy at work and there were some issues and resentments around commitment to the extended family, and John’s belief that he needed to please people. These meant time commitments to complete homework tasks became a problem, and some strategies needed to be used in terms of John learning to say no to his extended family at times to allow him to commit more time to his partner.

John was asked to complete ‘wax and wane’ masturbation tasks alone, whereby he would self‐stimulate until achieving an erection and then let the erection diminish, repeating this process three times before climaxing on the fourth. The rationale for this exercise was to help him to learn that his erection can return if it diminishes. This exercise worked well, and John’s confidence and self‐belief in his erections improved.

Simultaneously, the couple started a sensate focus programme, starting with a sex ban. John found it helpful that the pressure to ‘perform’ had been removed and the couple were able to progress throughout the programme, which incrementally introduced more sexually‐focused touching. They were able to enjoy intimacy in their relationship, learning to take pleasure from touching the whole body without overt focus on genitals and the perceived need to get and keep an erection. During the first stages of sensate focus, John reported intrusive thoughts around feeling that his penis ‘should’ become erect during the task, which can be a common concern for patients during these early stages. The rationale for the exercise needed to be reiterated: that getting an erection is not important, but instead to be able to focus on and enjoy pleasurable sensations of being touched and touching his wife. Once John had become confident with his ‘wax and wane’ exercises, and the joint sensate focus exercises had progressed to incorporate genital touching, his wife was asked to use the ‘wax and wane’ technique on John during the sensate focus session. This was used to build John’s confidence that his erection can also return during partnered sexual activity. This exercise worked well and eventually the couple were ready to try penetrative intercourse, with his wife initially being asked to insert John’s penis into her vagina when hard, without thrusting, and hold it there for a few moments before removing it and continuing stimulation with her hand.

The exercises progressed to incorporate thrusting movements, and at this point John’s wife reported that he would start to move rapidly, returning to his old behaviour of trying to maintain the erection. On returning to this behaviour, John found he started to lose his erection. John was asked to slow it down and allow his wife to set the pace; however, his urge to rapidly thrust was difficult to resist. Both partners were upset by this setback and became anxious that the problem would not resolve. At this point, following discussion, John’s GP was asked to prescribe daily tadalafil (5mg to be reduced to 2.5mg, depending on response). John responded well to this and was able to maintain an erection during the exercises, which gave him the confidence he required to continue with the psychosexual treatment programme. He reduced the tadalafil to 2.5mg daily and was able to maintain an erection even after he had stopped taking the medication. This cessation was not planned (he had forgotten to request a repeat prescription before a holiday and the couple had still managed to have successful penetrative intercourse). John was discharged from therapy at this point as the couple reported a significant improvement in their general as well as sexual relationship.

Conclusion

A 2005 study of men in Scotland11 concluded that there was a widespread reluctance for men to seek help for medical and mental health difficulties, as help‐seeking behaviour challenged conventional views on masculinity. Add sexual dysfunction into this dilemma and it is hardly a surprise that men can take a long time to seek help until the problem and associated behaviours have become extreme.

Although a proportion of men do seek psychosexual help for sexual dysfunction, this trend may have changed in recent years with the advent of over the counter phosphodiesterase type 5‐inhibitors, such as Viagra Connect. Further research on men’s trends in help‐seeking from healthcare professionals would therefore be of significant interest. It is paramount that it becomes routine practice for healthcare professionals to ask men about their sexual function, and that we have the skills, knowledge and confidence to advise and refer appropriately.