https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10508-018-1301-9

Grubbs, Perry, Wilt, and Reid (2018a) proposed a model for understanding individuals’ problems with pornography due to moral incongruence (PPMI). Specifically, they posit that some pornography users experience psychological distress and other problems because their behaviors do not align with their personal values (i.e., moral incongruence), and previous research has lent support for this proposed model (Grubbs, Exline, Pargament, Volk, & Lindberg, 2017; Grubbs, Wilt, Exline, Pargament, & Kraus, 2018b; Volk, Thomas, Sosin, Jacob, & Moen, 2016).

In their article, Grubbs et al. (2018a) proposed two pathways for problematic use of pornography. Pathway 1 illustrates that pornography-related problems are due to dysregulation (i.e., compulsive use), and Pathway 2 describes pornography problems due to moral incongruence. Both pathways consider the subjective experience of distress which we agree is an important issue to address in individuals seeking treatment for problematic use of pornography. In our clinical practice, we have found that the subjective experience of distress, stemming from a combination of anxiety, shame, and/or guilt, is often a catalyst for clients seeking help. However, in order to provide appropriate treatment recommendations for individuals, including those who self-identify as “porn addicts,” we need to determine the degree to which they can control their sexual behavior. We have found that many clients seeking treatment for problematic use of pornography report significant distress along with numerous failed efforts to moderate or abstain from the behavior, experiences of negative or adverse consequences from their use, and continue their use despite deriving little pleasure from it.

The diagnostic framework around compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) has been hotly debated in recent years (Kraus, Voon, & Potenza, 2016b). CSB has been conceptualized as sexual addiction (Carnes, 2001), hypersexuality (Kafka, 2010), sexual impulsivity (Bancroft & Vukadinovic, 2004) or behavioral addiction (Kor, Fogel, Reid, & Potenza, 2013). As the debate has progressed, we have appreciated the concerns raised by a number of researchers (Moser, 2013; Winters, 2010) regarding the potential for over-pathologizing engagement in frequent sexual behaviors, which is why we believe that it is essential to look for the presence of behavioral patterns or additional objective indicators that the frequent sexual activities are problematic and uncontrollable (Kraus, Martino, & Potenza, 2016a).

As discussed by Kraus et al. (2018), further research with robust data is needed to support the development of an accurate diagnostic framework for CSB, including excessive use of pornography (Gola & Potenza, 2018; Walton & Bhullar, 2018). Additionally, we agree with Grubbs et al. (2018a) that current understanding of perceived addiction to pornography has cultural limitations since previous studies mainly took place in Western, industrialized countries with predominately Christian samples. This is a significant limitation to consider for how problematic pornography use is defined and treated since the norms, value systems, and experiences of individuals from other cultural backgrounds may differ from the well-studied Western Judeo-Christian perspectives regarding pornography use and other sexual behaviors. Further research on problematic use of pornography is needed to ensure that diagnostic criteria are not only accurate but also translatable across cultures.

Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD): Considerations for Differential Diagnosis

Recently, the World Health Organization (2018) recommended including CSBD in the forthcoming 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (6C72). A conservative approach was taken, and CSBD was classified as an impulse control disorder because research evidence is not yet strong enough to propose it as an addictive behavior. As a result, CSBD criteria include the following:

CSBD is characterized by a persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges resulting in repetitive sexual behavior. Symptoms may include repetitive sexual activities becoming a central focus of the person’s life to the point of neglecting health and personal care or other interests, activities and responsibilities; numerous unsuccessful efforts to significantly reduce repetitive sexual behavior; and continued repetitive sexual behavior despite adverse consequences or deriving little or no satisfaction from it. The pattern of failure to control intense, sexual impulses or urges and resulting repetitive sexual behavior is manifested over an extended period of time (e.g., 6 months or more), and causes marked distress or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Distress that is entirely related to moral judgments and disapproval about sexual impulses, urges, or behaviors is not sufficient to meet this requirement (World Health Organization, 2018).

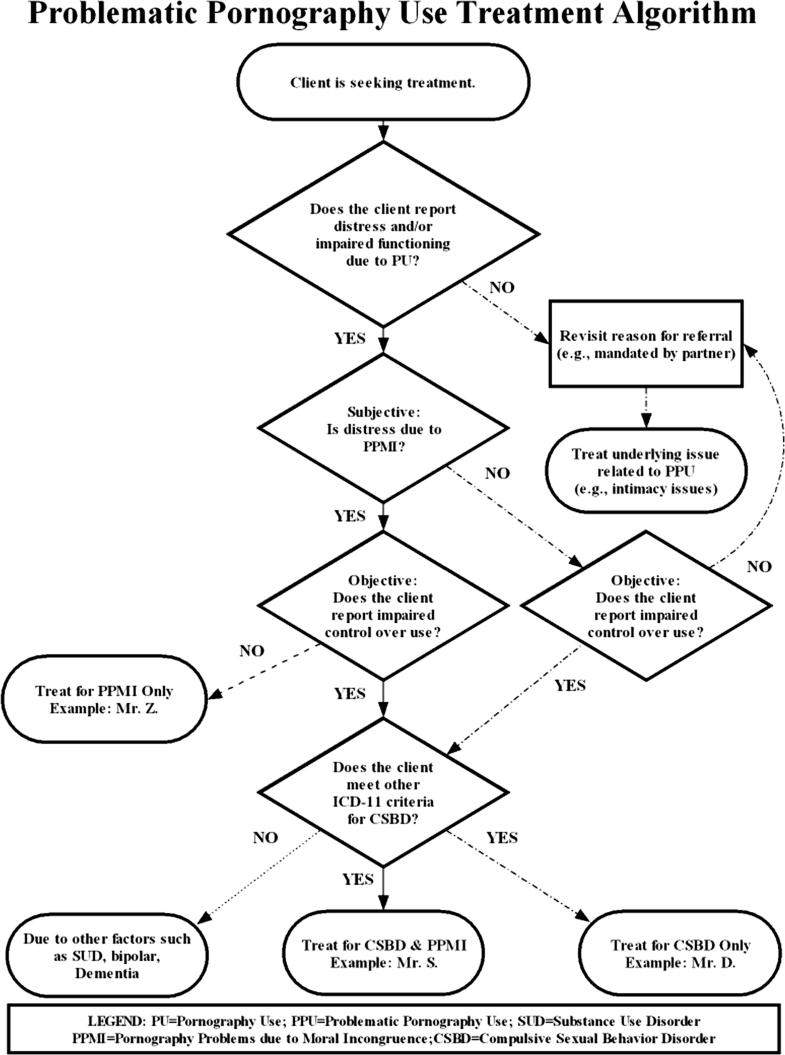

The hallmark of CSBD is repeated failed attempts to control or suppress one’s sexual behavior that causes marked distress and impairment in functioning, and “psychological distress due to sexual behavior by itself does not warrant a diagnosis of CSBD” (Kraus et al., 2018, p. 109). These are important points to consider in clinical practice where the key ingredients for any successful case conceptualization and treatment plan begin with a thorough assessment and appropriate differential diagnosis. We have developed the algorithm in Fig. 1 to help clinicians conceptualize diagnosis and treatment approaches for clients presenting with problematic use of pornography.

To aid understanding, we will now discuss three examples of real clients who sought treatment for problematic use of pornography in an Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) outpatient mental health specialty clinic. The examples have all been de-identified in order to protect the confidentiality of the clients.

Fig. 1

Problematic pornography use treatment algorithm

Individual with PPMI and CSBD

Mr. S is a biracial, heterosexual, single male veteran in his 20s who works part-time while attending college. He is being treated at the VA medical center for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression related to military combat. Mr. S also sought treatment because he self-identified as a “porn and sex addict” and reported using pornography since he was a teenager. He stated that he uses pornography daily. He described numerous attempts to quit using pornography as well as engaging in casual sex with acquaintances and paid sex workers. Mr. S described himself as a reformed evangelical Christian and stated that his pornography use and other sexual behaviors were “shameful” and “sinful” to him which resulted in significant psychological distress. Mr. S denied any past treatment for CSBD but reported attending a church men’s group for support because of his pornography use.

During the clinic’s intake, Mr. S’s responses to the assessment process followed the trajectory of the middle pathway in Fig. 1. He endorsed PPMI since his sexual behaviors did not align with his religious beliefs. By his history and report of current problems, he also met full criteria for CSBD. Unfortunately, Mr. S did not engage in subsequent treatment with our clinic given his interest in seeking help solely through his church. Prior to premature termination, the treatment recommendations for Mr. S included prescribing medication (naltrexone) to address his craving and providing cognitive behavioral therapy to address underlying beliefs and behaviors that resulted in his compulsive use of pornography.

Individual with CSBD Only

Mr. D is a Caucasian, heterosexual, married male veteran in his early 30s with a history of depression who self-identified as being “addicted to porn.” He began using pornography regularly in his early teenage years and engaged in frequent masturbation to pornography for the past 10 years, in particular viewing pornography for longer periods of time when his wife traveled for work. He reported satisfactory sexual activity with his wife although he felt that his pornography use was interfering with his intimacy and relationship with her. Mr. D described his pornography use as compulsive and reported little to no satisfaction from it. He reported intense urges to view pornography after several days of deprivation which then triggered his use.

During the clinic’s intake, Mr. D did not endorse experiencing distress due to PPMI but did experience difficulties controlling his pornography use. He was assessed and found to meet full ICD-11 criteria for CSBD as depicted in Fig. 1. Mr. D was prescribed medication (naltrexone, 50 mg/day), and he also participated in individual sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorders that were adapted to address his problematic pornography use. Over the course of treatment, Mr. D decreased his pornography use and coped effectively with his cravings. He also reported an increase in engaging in pleasurable activities with his wife and friends such as hiking and traveling.

Individual with PPMI Only

Mr. Z is a Caucasian, heterosexual male combat veteran in his early 40s who has been married for several years. He is employed and has one child. Mr. Z reported a history of depression and also using pornography on and off for the past 20 years which led to conflicts with romantic partners, including his current wife. He denied using pornography during periods where he was sexually active with his wife, but stated that he had not been physically intimate with her in several years. At present, he viewed pornography once or twice a week to masturbate but denied any difficulty stopping or cutting back. He reported using pornography mainly because he has no other sexual outlet, but his pornography use makes him feel “horrible” and “disgusting” because his behavior was incongruent with his beliefs about how men “should behave” in the context of marriage. He experienced profound distress, particularly depression, related to the level of incongruence between his values and his sexual behaviors.

During the clinic’s intake, Mr. Z stated that he has never sought treatment for this issue before. He endorsed subjective experiences of distress due to PPMI and met diagnostic criteria for both depression and anxiety disorders but not CSBD as represented in Fig. 1. Individual therapy focused on reducing Mr. Z’s anxiety regarding initiation of sexual intercourse with his wife. Mr. Z and his wife also participated in couples therapy where the therapist assigned non-sexual pleasurable activities for the couple to do while also increasing their communication. Mr. Z reported a decrease in pornography use when he and his wife resumed physical intimacy. He also reported increased communication with his wife as well as decreased depression and anxiety which subsequently led him to discontinue treatment.

Final Comments

Our intention with this Commentary is to continue the needed dialogue about diagnostic considerations for clients seeking treatment for problematic use of pornography. As discussed by Grubbs et al. (2018a), the topic of moral incongruence is relevant when determining whether a client with problematic pornography use meets ICD-11 criteria for CSBD. Evidence suggests that some individuals report significant issues moderating and/or controlling their use of pornography leading to marked distress and impairment in many areas of psychosocial functioning (Kraus, Potenza, Martino, & Grant, 2015b). With the possible inclusion of CSBD in ICD-11 and high prevalence of pornography use in many Western countries, we anticipate that more people will seek treatment for problematic pornography use in the future. However, not all who seek treatment for problematic pornography use of pornography will meet criteria for CSBD. As discussed earlier, understanding the reasons behind clients’ decisions for seeking help for problematic use of pornography will be crucial in order to appropriately determine accurate diagnosis and treatment planning for clients.

As highlighted by our client examples, it is necessary to tease apart the nature of problematic pornography use for diagnostic clarification and appropriate treatment recommendations to be offered. Several treatments have been already developed and piloted for CSB, including problematic use of pornography. Preliminary evidence supports the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (Hallberg, Kaldo, Arver, Dhejne, & Öberg, 2017), acceptance commitment therapy (Crosby & Twohig, 2016) or mindfulness-based approaches (Brem, Shorey, Anderson, & Stuart, 2017; Reid, Bramen, Anderson, & Cohen, 2014). Additionally, there is some evidence to support pharmacological interventions (Gola & Potenza, 2016; Klein, Rettenberger, & Briken, 2014; Kraus, Meshberg-Cohen, Martino, Quinones, & Potenza, 2015a; Raymond, Grant, & Coleman, 2010). As shown in our client examples and Fig. 1, clients with problematic pornography use have diverse clinical presentations and reasons for seeking help. Therefore, future research is needed to develop treatments that appropriately address the complexity and nuances of issues underlying problematic use of pornography.

Notes

Funding

This work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, VISN 1 New England Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose for the content of the current study. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, USA.

Ethical Approval

All ethical guidelines were followed as required by the Department of Veteran Affairs. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. The use of de-identified case vignettes was included for training purposes only.

References

-

Bancroft, J., & Vukadinovic, Z. (2004). Sexual addiction, sexual compulsivity, sexual impulsivity, or what? Toward a theoretical model. Journal of Sex Research, 41(3), 225–234.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Brem, M. J., Shorey, R. C., Anderson, S., & Stuart, G. L. (2017). Dispositional mindfulness, shame, and compulsive sexual behaviors among men in residential treatment for substance use disorders. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1552–1558.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Carnes, P. (2001). Out of the shadows: Understanding sexual addiction. New York: Hazelden Publishing.Google Scholar

-

Crosby, J. M., & Twohig, M. P. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy for problematic internet pornography use: A randomized trial. Behavior Therapy, 47(3), 355–366.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Gola, M., & Potenza, M. (2016). Paroxetine treatment of problematic pornography use: A case series. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(3), 529–532.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Gola, M., & Potenza, M. N. (2018). Promoting educational, classification, treatment, and policy initiatives: Commentary on: Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder in the ICD-11 (Kraus et al., 2018). Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 208–210.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Volk, F., & Lindberg, M. J. (2017). Internet pornography use, perceived addiction, and religious/spiritual struggles. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(6), 1733–1745.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Grubbs, J. B., Perry, S. L., Wilt, J. A., & Reid, R. C. (2018a). Pornography problems due to moral incongruence: An integrative model with a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1248-x.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Grubbs, J. B., Wilt, J. A., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., & Kraus, S. W. (2018b). Moral disapproval and perceived addiction to internet pornography: a longitudinal examination. Addiction, 113(3), 496–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14007.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Hallberg, J., Kaldo, V., Arver, S., Dhejne, C., & Öberg, K. G. (2017). A cognitive-behavioral therapy group intervention for hypersexual disorder: A feasibility study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14(7), 950–958.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Kafka, M. P. (2010). Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 377–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Klein, V., Rettenberger, M., & Briken, P. (2014). Self-reported indicators of hypersexuality and its correlates in a female online sample. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(8), 1974–1981.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Kor, A., Fogel, Y., Reid, R. C., & Potenza, M. N. (2013). Should hypersexual disorder be classified as an addiction? Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 20(1–2), 27–47. CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Kraus, S. W., Krueger, R. B., Briken, P., First, M. B., Stein, D. J., Kaplan, M. S., … Reed, G. M. (2018). Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder in the ICD-11. World Psychiatry, 1, 109–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20499.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Kraus, S. W., Martino, S., & Potenza, M. N. (2016a). Clinical characteristics of men interested in seeking treatment for use of pornography. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(2), 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.036.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentralGoogle Scholar

-

Kraus, S. W., Meshberg-Cohen, S., Martino, S., Quinones, L. J., & Potenza, M. N. (2015a). Treatment of compulsive pornography use with naltrexone: A case report. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(12), 1260–1261. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15060843.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Kraus, S. W., Potenza, M. N., Martino, S., & Grant, J. E. (2015b). Examining the psychometric properties of the Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale in a sample of compulsive pornography users. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 59, 117–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.02.007.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Kraus, S. W., Voon, V., & Potenza, M. N. (2016b). Should compulsive sexual behavior be considered an addiction? Addiction, 111, 2097–2106.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Moser, C. (2013). Hypersexual disorder: Searching for clarity. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 20(1–2), 48–58.Google Scholar

-

Raymond, N. C., Grant, J. E., & Coleman, E. (2010). Augmentation with naltrexone to treat compulsive sexual behavior: a case series. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 22(1), 56–62.PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Reid, R. C., Bramen, J. E., Anderson, A., & Cohen, M. S. (2014). Mindfulness, emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, and stress proneness among hypersexual patients. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(4), 313–321.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Volk, F., Thomas, J., Sosin, L., Jacob, V., & Moen, C. (2016). Religiosity, developmental context, and sexual shame in pornography users: A serial mediation model. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 23(2–3), 244–259.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Walton, M. T., & Bhullar, N. (2018). Compulsive sexual behavior as an impulse control disorder: Awaiting field studies data [Letter to the Editor]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1327–1331.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

Winters, J. (2010). Hypersexual disorder: A more cautious approach [Letter to the Editor]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(3), 594–596.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

World Health Organization. (2018). ICD-11 for mortality and morbidity statistics. Geneva: Author.Google Scholar