Abstract

In Japan more young people became sexually inactive in 2000s, especially since around 2005.On the other hand, Internet and digital technology were spread in the same period. In this paper, five phases of Internet and digital technology are investigated to realize what happened to the sexuality of Japanese youth associated with the technology: e-mail and SNS, online pornography, fantasy world of Otaku leisure, dating sites and applications, sexual service industry. Online pornography of extreme contents and strong stimuli with completely male-centered vision overflew in the 2000s. With the influence, both men and women have got difficulties in having real sex. Animations and games to satisfy the romantic needs and libidos of the youth gained popularity in 2000s,to overwhelm real romance and sex. In the last part, the need of cross-cultural comparative studies on technology and sexuality is insisted.

Keywords

Internet Online pornography Otaku culture Japanese youth Sexual inactivation

Modern societies around the world are said to be in the midst of a permanent revolution in sex and intimacy (Weeks 2007). It would be valuable for sociology to accurately capture these revolutions, as they affect a wide range of social life, including leisure, human rights, and family life, as well as social sustainability by replenishing the population. These revolutions are influenced by the religion, history, family system, and economics of each society and differ significantly from each other (Hekma and Giami 2014). There are also areas in the world where we doubt revolutions really occur. However, sexuality has been studied and discussed mainly as a phenomenon of Western societies. Paying attention to relevant transformations in non-Western societies will give us a clearer overall picture of the revolution.

Since the 2000s, many societies in the world have experienced the Internet and digital revolution—the development and spread of this new technology. During this period, quantitative and qualitative changes in devices and services have been very fast and broad. Technology has dramatically changed communication, encounters, cognition, and imagination. Hence it has changed sex and romance in complicated and profound ways (Attwood 2018; Turkle 2012).

Internet technology expanded the possibilities of in-person sexual encounters or romantic relationships, and supported sex and intimate activities (Kon 2001). However, the Internet and digital technology has also dramatically expanded sexual imaginations by offering a new digital leisure activity, and it inhibits direct, unmediated sexual encounters and intimacy (Honda 2005). This is one of the contradictions of modern sexuality (Weeks 2007): Does the Internet and digital technology in the new millennium activate the leisure of direct sexual activity? Or does the technology cause people to withdraw from in-person sexual encounters and romance into a closed world of fantasy or delusion? The result is brought about by the complex interaction between the new technology and sexuality.

Along with the advances in Internet and digital technology, various forms of sexual depression have been reported one after another in Japan since around 2000. However, the details of how each form of sexual depression was related to a certain aspect of information technology have, thus far, not been sufficiently analyzed. In Japan, it is often said that people started having less sex after the spread of the Internet. However, there is no empirical proof of this yet.

In this paper, we will examine the interplay between sexuality and Internet or digital technology, and the consequences thereof. We will focus on young people, from teenagers to twentysomethings, who are highly exposed to and impacted by new information technologies. In this paper, information technologies refer to mobile services, SNS (social networking services), games, adult sites, matching sites, and applications, as well as various other devices, services, and applications. They all seem likely to be related to the reduction in sexual activity. We will draw the whole picture by reviewing previous research data on the use of mobile phones, SNS, games, adult sites, matching sites and applications, and relevant data on sexuality.1

In the first chapter, we will review the shifts in the sexual consciousness and behavior of Japanese youth and also describe the factors considered to affect the shifts other than information technology. In the following chapters, we will look back at the shifts concerning information technology since 2000 in Japan, in the five phases considered to be related to the change in sexual consciousness and behavior, and will try to determine how it relates to the change in sexuality. In the last part, we will hypothesize several factors other than those discussed earlier. After that, we will propose possible solutions to sexual depression that became serious in the development of information technologies. We will also point out some research topics to be addressed in the future regarding information technology and sexuality.

1 Sexual Consciousness and the Behavior of Japanese Youth since 2000: Inactivation, Indifference, and Negative Image As Well as Diversification

Since around 2000, the sexual activities of young people in Japan underwent a complex change. The differences among subgroups due to economic and social status, generation, geographical region, etc. have been big. There were and are many young people who are sexually active; we cannot assume that the Japanese are uniformly sexually inactive. However, we know for certain that the rate of sexual inactivity among Japanese youth has increased since around 2005.

The phenomenon of sexless couples2 was pointed out in the 1990s and became a social concern from the 2000s onwards. The surveys found that the rate of sexless couples continued to increase. More recently, in 2016, 47.2% of married couples (aged 16 to 49) were sexless (JAFP 2017; Pacher 2018).3 The rate of sexless couples has increased even among young people. The younger generation,because more of their parents are sexless, are thought to have greater difficulty in combining an intimate family life and sex than the previous generations.

Moreover, more young people are remaining single and not having sex. The rate of the unmarried among young people has increased constantly since around 1975. Furthermore, in the 2000s and afterwards, the percentage of unmarried people without a dating partner increased. The proportion of unmarried people aged 20–24 with no dating partner increased from 38.7% in 2002 to 55.3% in 2015 for women, and from 48.8% in 2002 to 67.5% in 2015 for men (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research). The percentage of single people who have never had a dating partner has also increased. The rate of unmarried people with no sexual experience (aged 20–24) was 36.3% in 2005 and increased to 46.5% in 2015 for women. For men it was 33.6% in 2005 and increased to 47.0% in 2015 (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research).4

As we see, since the 2000s, more young people have become sexually inactive. There are possibilities for sexual activity outside couplehood, such as prostitution. However, those activities have not increased in the same period enough to compensate for the decline in sex between couples (although no statistical survey has been done on this). Detailed research on sexual activities outside of couples is needed.

These phenomena of sexual inactivation cannot be explained by a single factor. However, the increase in the numbers of young men and women with irregular employment (overlapping with the poor) can be considered a major factor. These young people, who have not thought about such a life with economic poverty in growing up, are anxious about living expenses and unemployment and have little room to think about dating, romance, and marriage (Sato and Nagai 2010). Men with irregular jobs are especially prone to lose confidence in their situation, in which their living standards are far below what they expected (Okubo et al. 2006). As partners in love and marriage, women prefer men with stable, full-time jobs and good income (Cabinet Office 2011). Therefore, men with irregular employment tend to think: “I do not want to get married” or “I am not interested in romantic love” and stay by themselves.5

On the other hand, young people who are regularly employed tend to be exhausted due to overwork. The number of people suffering from depression or even committing suicide due to overwork has been increasing (Kumazawa 2018). Many of them feel neither affection nor love. Even if they get married, they become sexually inactive (Genda 2010).

According to the 2005 survey of Yushi Genda and Aera magazine (targeting those who were employed and who were married or cohabiting with partners), among both men and women, those who had experienced work frustrations such as demotion and unemployment were far more likely to be “not having sex at all” with their partners than those who had not experienced such setbacks in the same age group. For women, work frustration was more closely correlated with sexlessness than it was for men. The survey also found that a bad “workplace atmosphere” was clearly related to sexlessness. The JGSS survey revealed (combining the results of the surveys in 2000 and 2001) that among the wives in their twenties and thirties, 9.8% of those who had never been unemployed were sexless, while 23.5% of those who had ever been unemployed were sexless. This difference was bigger than the case of husbands of the same age group. Genda and Saito quote a woman in her twenties who had been having sex once or twice a week with her husband but was no longer willing to have sex after she was dismissed. “When I am really exhausted and my husband insists that we have sex, I never get an orgasm. I want to sleep as much as possible and want our sex to end quickly. Sex life is quite susceptible to work stress” (Genda and Saito 2007).

Thus employment, labor, and economic problems definitely caused sexual depression in the 2000s, as the long-term recession unfolded.

Compared to working people, one would expect that junior high school, high school, and university6 students are much less affected by employment, labor, and economic problems (though university students would be more affected). However, these students have also reduced their sexual activities since around 2000 or 2005.

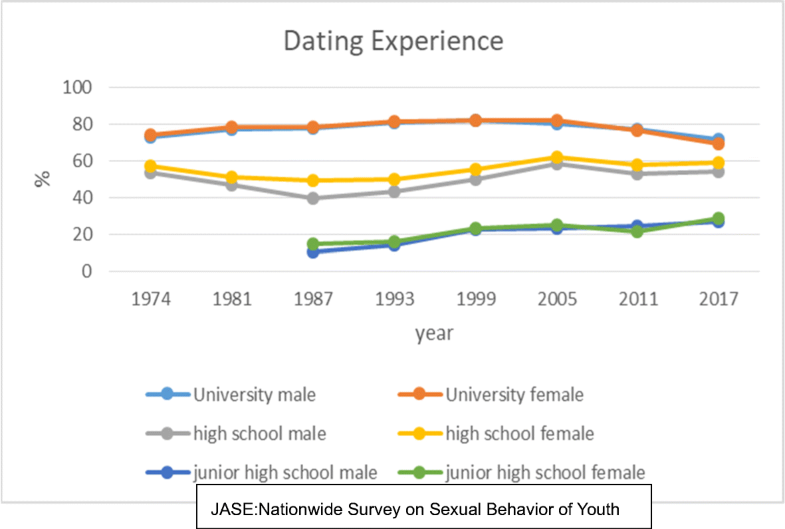

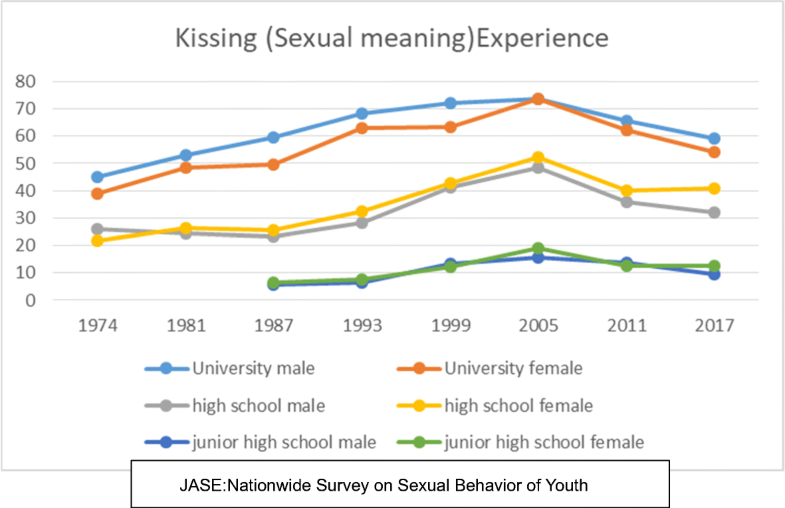

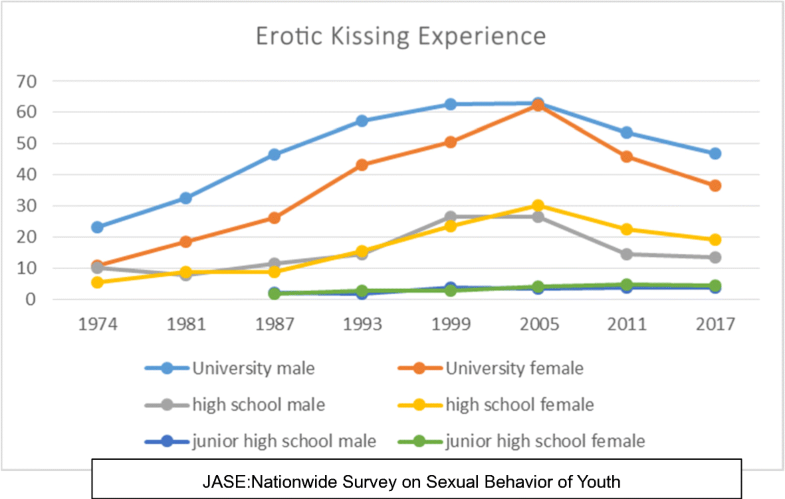

According to JASE’s Nationwide Survey of the Sexual Behavior of Young People, conducted eight times since 19747, dating experience levels grew up until 1999 and stabilized between 1999 and 2017 among junior high school, high school, and university students (Fig. 1) as co-education spread. On the other hand, kissing (Fig. 2) and sex (Fig. 3) increased until 2005 and thereafter declined until 2017.

Fig. 1

Rates of dating experience did not change much for more than 40 years

Fig. 2

Rates of erotic kissing experience increased until 2005, then decreased until 2017

Fig. 3

Rates of sex experience increased until 2005, then decreased until 2017

We can observe in these shifts that kissing and sexual experience among junior high school, high school, and university students had advanced before the Internet and digital revolution. In Japan, social acceptance of premarital sex has spread since the 1970s. In the 1980s and 1990s, dating and sex became more common among young men,before they became common among young women. Sexual activities were pursued utilizing the media of landline phones and pagers, before the era of high-tech personal communication media (Takahashi 2007).

Since young students were most sensitive to the influence of the information revolution, in order to be accurate, it is impossible to point out the factors of their sexual depression that are irrelevant to the new information technology. However, we will dare to show the factors not directly related to the new technology. The following four points are the factors found in previous research.

First, statistical analysis of the JASE survey revealed that a change in the young students’ study habits was a factor in their sexual deactivation. In the 2000s and afterward, the students began studying more intensely and for longer instead of going on holiday (Katase 2018). We assume that their intense study was motivated by economic and social uncertainty.

Second, statistical analysis of the JASE survey found that in the 2000s, young people discussed sex and romance with their friends less and less often. It is also found from the analysis that young students who talk about sex with friends have a positive image of sex. But because of the multipolarization of youth concerning sexuality and because of the spread of the Internet, young students shifted from conversations with friends about sex to searching on the Internet, which provides a less positive image of sex (Harihara 2018).

Third, the risks involved in sex were also found to be a factor. After about the year 2000, sex education at school started focusing mainly on (and in many cases only on) the risk of pregnancy and STDs (socially transmitted diseases). As a consequence, young people stopped having uninformed and reckless sex, but tended to fear sex in general (Katase 2018, 192).

Fourth, since the mid-2000s there was a drop in interest in romance, especially among women. From the 1990s until around 2005, many women, including female students, shared a way of thinking that placed love above all. Women tended to have sex to express their love, even though they were not very interested in sex. Since the mid-2000s, the romance trend has greatly declined, and the number of young women who do not want lovers has increased (Tsuchida 2018).

These four points are the main factors in the sexual deactivation of the youth, other than the factors related to Internet and digital technology. In the next chapter we will investigate the factors related to Internet and digital technology. Then in the last part, we will state our hypothesis on other factors responsible for the sexual depression.

2 Developments in Information Technology and the Change in Sexual Consciousness and Behavior

2.1 Communication Via E-Mail and SNS

In Japan, PC (personal computer) and mobile phone use have dramatically increased since 1995. Young people in particular have responded quickly to new media. In 2000, the rate of mobile phone ownership among college students increased to 94.4% (Futakata 2006, 87). The overall Internet usage rate on PCs also continued to rise.

Styles of communication media usage among youth are not uniform; they are divided between the mobile phone and the PC. A 2005 nationwide survey by JASE found many differences between the two groups, including social class, school type, education level, friendship behavior, and sexual behavior (JASE 2007). Heavy users of mobile phones and mobile text messages tended to not enroll in university, to spend a lot of time in town with friends, and to be sexually active. On the other hand, heavy users of PCs8 tended to enroll in colleges or universities, were relatively introverted, tended not to hang out in the city, and were sexually inactive. All junior high school, high school, and university students who were heavy users of mobile phones or e-mails had a higher rate of dating, kissing, and sex than those who were heavy users of PCs. The proportion of 20-year-olds who have had more than three sex partners was more than 60% among heavy users of mobiles, 20% among light users of mobiles, and 18% among heavy users of PCs; the rates were significantly different. In high school, the percentage those who had met someone of the opposite sex in person for the first time after an e-mail exchange was 58.4% among males who were heavy users of mobiles, and 59.3% among females who were heavy users. On the other hand, the rate was as low as 19% among males who were heavy users of PCs, and 21.3% among females who were heavy users of PCs. In high school, 56.3% of males who were heavy users of PCs, and 39.7% of males who were heavy users of mobiles, used adult sites. The two groups have notable differences9 (Takahashi 2007).

Young people who used mobile phones when mobile phones and PCs were just beginning to be popular, until around 2005, expanded their personal connections through media communication (such as e-mail friends), went on to meet people in person, and strengthened their relationships through private communication (Asano 2006). Mobile dating sites also became popular, to the extent that 12.1% of male university students and 6.5% of female university students used them to meet new people in 2005 (JASE 2007). From their first appearance on the market through about 2005, mobile phones incorporated dramatic technical improvements each year (text messaging in 1997, Internet connection in 1999, mobile phone cameras in 2000, and so on). The relatively limited information displayed on the small screen of the mobile phones drastically broadened the possibility of a face-to-face encounter, but they did not offer fascinating virtual worlds to distract the users from face-to-face meetings.

On the other hand, during the same period, e-mail communications on PCs did not lead to in-person encounters or promote sexual relationships. In fact, concerning sexuality, PCs were only used individually for adult sites (JASE 2007).

From the 1990s to the mid-2000s, romance became a boom and was told in all media such as popular songs, magazines and TV dramas especially for young generation. Opportunities for men and women to meet each other in schools and workplaces increased, and in the 1990s, love and marriage already became perceived as different things (Yamada 1996). Thus young people engaged in serial relationships and tended to postpone marriage. It was no longer rare for people to have multiple sexual relationships at the same time (Tanimoto 2008, chap. 3).

Among teenagers and young women, the phenomenon of “compensated dating” (dating, giving their underwear to, or having sex with adults for money or gifts) arose, provoking social controversies in the second half of the 1990s (Enda 2001). As many as 4% of female high school students in Tokyo have had such experiences, according to a survey by Asahi Shinbun (Asahi Shinbun, September 20, 1994). Many men with no consideration on the lives of women purchased “dates” with high school girls or young women (Enda 2001). In reaction to this phenomenon, the value of romantic love also increased among female high school and university students (JASE 2007). All types of relations, ranging from romantic love and friendship, romantic love and marriage, romantic love and sex, self and other, were greatly shaken in this period, which generated strong social concerns. The spread of mobile phones and the PCs occurred in the midst of this complicated shift.

It can be said that through the mid-2000s, early mobile phones supported and powerfully boosted the romance boom that started before the Internet era and activated sexual activities accompanied with romance. Mobile phones greatly expanded the social relationships of young people and also promoted communication between people of the opposite sex (JASE 2007, 65–72).

The rapid popularization of the Internet, mobilizing social segments and social relations, also brought people a vague sense of uneasiness. Because of this uneasiness, young people eagerly searched for love. Various forms of love were tried: pure love, multiple love, love as play, love as friendship, and so on (Tanimoto 2008).

Especially among young women, the proportion who thought that “love is necessary for sex” increased significantly. Young women at this time tended to search for love and to have sex with their boyfriends to express their love for them, even if the women did not necessarily want to have sex for its own sake (JASE 2007, 87). Thus the percentage of female high school and university students who had had sexual experience increased from 1999 through 2005 (JASE 2007, 15).10

Mobile phones increased the frequency of communication between couples, promoted closeness, and accelerated the relationship. Heavy users of mobiles began dating, kissing, and having sex with a partner earlier than before (JASE 2007, 72–76).

In Japan, mobile phones promoted another kind of sexual activity. Around the year 2000, the the media used for advertising and negotiating “compensated dating” and prostitution quickly shifted, from fixed phone to mobile phone and to mobile dating sites. From the latter half of the 1990s through the 2000s, more women lost their resistance to involvement in compensated dating and prostitution.11 The reasons why women were willing to try these activities are very complicated, and in some cases the women themselves were not entirely sure why. We know for certain that through the 2000s, the proportion of those living in poverty increased (Nito 2014). However, there is no doubt that mobile Internet technology, where anonymous and unspecified people can easily meet, promotes compensated dating and prostitution.

In the long-term recession from the early 1990s onwards, men continued to enjoy an economic advantage over women. The romance boom mentioned above can be said to have this background. However, starting in the mid-2000s, especially after the financial crisis of 2008, the unemployment or irregular employment of young men increased drastically. The romance boom and women’s interest in “winning” relationships diminished (Ushikubo 2015). What remained in the space of mobile Internet was only the advertisements and messages for compensated dating and prostitution.

In this way, all the mobile mailboxes and mobile dating sites in Japanese became forever tainted by prostitution-related messages that could not be ignored.

Since the mid-2000s, various SNS such as 2-chan and Mixi have been widely adopted. SNS culture became increasingly diversified, and various types of young people participated. Each community has its unique vocabulary, grammar, and esthetics, and the participants develop a sense of fulfillment and belonging. Gradually, communication on SNS became more attractive than face-to-face communication. People started using SNS to express themselves, form relationships, and belong to communities. Aside from Facebook, which requires the use of real names, communication and relationships on SNS became confined to the Internet. People began spending more time on SNS and having fewer in-person encounters. To invite someone of the opposite sex to a face-to-face encounter after exchanging messages on SNS, Japanese people need to improve their texting skills.

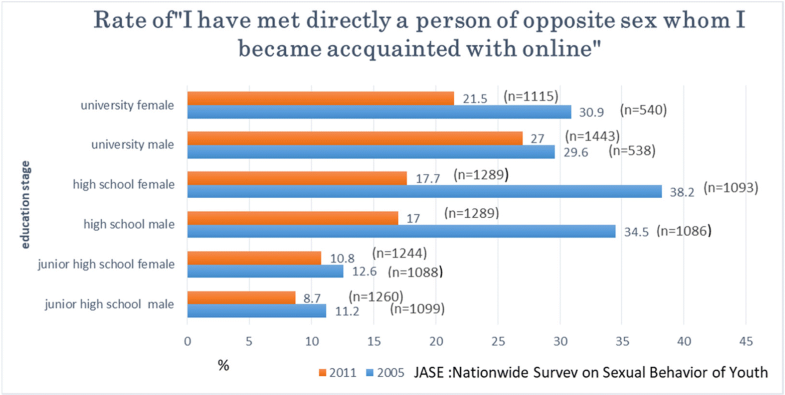

The rate of meeting someone of the opposite sex in person after getting acquainted online decreased drastically from 2005 to 2011, among both men and women with any level of education (JASE 2007, 2013) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Rates of meeting someone of the opposite sex in person after online acqueintance decreased from 2005 to 2011

As we see above, Japanese youth became more self-sufficient with communication only online and were reluctant to meet in person those of the opposite sex whom they met online.

2.2 Dating Sites and Applications

In Japan, a variety of dating sites could be accessed on personal computers since 1995. Mobile dating sites started in 1999. Young people, including teenage girls, quickly became users of the mobile dating sites (Ogiue 2011). They posted light, inviting messages such as: “Looking for a guy who can meet just now.” These led to a significant number of nanpa (hook-ups), encounters, and love affairs (Ogiue 2011). In the 1980s and 1990s, before the Internet era, phone-based systems for connecting strangers were already popular. Dating sites rapidly took their place in the Internet era. In 2005, 12.5% of male vocational school students, 17.6% of female vocational school students, 12.1% of male university students, and 6.5% of female university students reported that they had used dating sites (JASE 2007).12

Since their introduction, Japanese dating sites and applications were taken up by the messages of young women looking for compensated dating, and by staff of the sexual service agencies, just like the telephone services in the 1990s. The Dating Site Regulation Law, enacted in 2003, prohibits the sites inviting those under 18 to any kind of sexual activity. In addition, in 2008, the law was revised to require the real age of the user, certified by a public ID card, when registering on dating sites. As a result of this law, numerous dating sites were shut down. As a result, the media of compensated dating moved to SNS, which do not require age registration. Japanese dating sites were actually the basis for compensated dating and prostitution, especially before the law amendment (Ogiue 2011).

In addition, many illegal contractors acting as pimps for prostitutes have appeared on dating sites and applications, attracting the attention of male users with sexy pictures, profiles, and aggressive messages. Some guide male users to other paid sites. There have also been many dating sites set up by malicious vendors, which encourage male users to keep using the sites for a long time, at high fees. Male users receive many messages from women, which are fake messages written by the site’s own employees. By the time male users are all dissatisfied, the site suddenly closes, and another site opens.

Dominated by messages of compensated dating and prostitution, and messages from malicious vendors, dating sites and applications gained a reputation in the early 2000s as shady, immoral, and criminal. With the law amendment in 2008, dating site companies fundamentally changed their management in an effort to improve their reputation, by excluding pimps observing age restrictions, and unremittingly deleting the messages promoting prostitution (Ogiue 2011).

As described above, in Japan, dating sites and applications, which differed from those in Western countries (Spracklen 2015), had not been widely used as a means by which to find a partner until quite recently. Most Japanese are not yet used to writing attractive profiles and sending persuasive messages. In many Western societies, dating sites and applications on the Internet have greatly changed romance and sex, but in Japan this is not the case. The mobile app Tinder was also introduced to Japan, but it has not been widely adopted.

2.3 Sexual Service Industry

The Prostitution Prevention Law of 1957 remained the basis of contemporary legal restrictions on prostitution and sexual services in Japan. In this law’s definition of prostitution, the term “genital insertion” (sexual intercourse) is used. To work around this law, a variety of sexual services not involving genital insertion have developed. In 1999, the law on sexual services was amended to accept the delivery form of sexual services. A call-girl service called “delivery health” gradually became the main form of sexual service (Nakamura 2015a, b). In 2010, there were more than 15,000 delivery health offices, increasing to over 20,000 in 2017. On the other hand, the government has eliminated the sexual service salons on the streets. Since 2004, many salons have been forced to shut down after police raids (Ogiue 2011). In this way the form of sex services has shifted. The government’s policy was to clean out the red-light districts and to clean up the streets, but as the sex industry has moved underground, sex workers have been placed in even bigger danger.

It is certain that this shift went hand-in-hand with the development and spread of the Internet and digital technology. Delivery health sexual service agencies try to attract customers by making huge expenditures on online advertising. Photographs, profiles, and personal comments of the sex workers appear on the sites. There are also a myriad of sites to guide men to the sites of the agencies. There are even sites guiding beginners on how to be good customers. The total amount of online information on sexual services might far exceed the amount of information on couples and relationships on the Japanese sites.

Delivery health involves sexual services that should exclude genital insertion, but rape happens quite often in the hotel room or the customer’s private room (Nakashio 2016).

New forms of online sexual services were invented, such as adult chat services, in which the women (called “chat ladies”) and male customers have sexual conversations online (Ogiue 2011, 178).

Around 350,000 women in all are said to work in the sex industry today (Nakamura 2014). Women’s poverty has been severe in the 2000s and afterwards, due to a long recession and women’s economic disadvantages. The number of women in this industry increased in the 2000s. However, both the number of male customers and service prices dropped in the same period, because men’s economic power declined. Moreover, men purchased fewer sexual services than before. In a 1999 nationwide survey by NHK, more than 20% of men in their twenties, and 54% of men in their thirties, had used a sexual service in the past year (NHK 2002). Although no large-scale survey was done on the purchase of sexual services after the 2000s, the rate is thought to have declined considerably since 1999. Advertisements for sexual services have been overflowing on the Internet, but the use of sexual services has decreased in the Internet age. Only a few Japanese have compensated for the decline in couples sex by purchasing sexual services. However, the advertisements for sexual services flooding the Internet definitely continue to present sex as a service, thus influencing people’s consciousness.

As we see in these three sections above, information technology enabled young people to deepen and maintain relationships with their partners, and conduct mediated sexual communication in Japan as well. Moreover, technology offered young people the possibility of a wide range of encounters beyond the social groups to which they belonged. However, from the early 2000s to this day, the Internet is not trusted as a place to find a genuine, non-commercial encounter, since there are so many messages asking for compensated dating or prostitution. Of course, a small percentage of youth have pursued paid dating and sex, but the rate of and the market for sexual services have been shrinking (Nakamura 2014). On the other hand, 4.9% of men and women age 20 were reported to have had a relationship with someone they met online through SNS or matching applications in 2018 (Rakuten O-net 2018). This proportion is not so big. Thus Internet technology is not considered to have prompted actual sexual activity after mid-2000. Moreover, the sexual consciousness of many Japanese people may well have been greatly influenced by commercial sexual promotions and suspect Internet messages, just like brainwashing.

In the next two sections, we will investigate how the Internet and digital technology have developed media that provide self-sufficient sexual entertainment, and how actual sexual activities have been replaced. This discussion is based in part on the theory of Zimbardo and Coulombe (2015), which insists that the Internet and digital technology greatly impair men’s ability to build intimate relationships and sexual relationships in the interdisciplinary and comprehensive discussion of psychology, sociology, physiology, and so on. They mainly focus on the current situation in the United States, but we maintain that the situation is worse in Japan, due to several social circumstances.

2.4 Online Pornography

A considerable part of Internet development involves pornographic media. As Spracklen (2015) points out, “masturbating to pornography is the biggest form of leisure associated with the Net.” The Japanese porn industry has thrived for more than 40 years. From carefully hiding pubic hair to exposing it, from heavily pixillating images of genitals to only lightly pixillating them, from simulated sex to real intercourse, pornography gradually became more explicit in the 1980s and 1990s in order to be more stimulating. The numbers of rental video stores dramatically increased until the early 1990s, and the market boomed, especially from 1998 to 2002 (Fujiki 2009). The size of the market at that time was said to be 300 billion yen per year (Nakamura 2015a), when porn videos were available for sale or rental and there was fierce competition. Starting around 1995, online pornography joined this market competition.

In the late 1990s, sample sites of porn films, offering clips from three to 15 min long, were established and had a significant impact on the market expansion of Internet porn (Ogiue 2011). Moreover, in 2000, portal sites opened that introduced many new porn films and were also linked to many sample sites, forming a huge porn network (Ogiue 2011, 153). This development in online porn changed porn viewing behavior greatly; it became a far more accessible, and thus more frequent, experience.13 Accurate survey data is not available, but unlike in Western countries, in Japan it is very rare for couples to watch pornography together; men mostly watch by themselves, in secret. This seems to be an important factor behind the rise of extreme content in Japanese porn and the decline in couples sex.

In the late 2000s, due to the development of free video-sharing services, paid porn films and amateur porn films were also posted online and made available free of charge. With more people browsing, free-adult-video culture was enhanced (Ogiue 2011).

The technical changes and fierce competition in free video distribution online transformed adult films in a number of ways. The length of each film became extremely short. Before 2000, there were long videos that could be called human documents, or philosophical works. After that, however, most of them became very short—about 5 min, only long enough so a man could ejaculate. The films no longer had plots or descriptions of the characters’ personalities and relationships. The quality of actresses improved. The porn actresses were generally regarded as being engaged in a shameful occupation, and to a considerable degree, they are still seen that way today. However, because the porn stars earned money and popularity, more young women willingly entered the industry. Scouts aggressively sought out new porn actresses. The genres became more segmented. These changes seem to have influenced males’ sexual preferences. Between 2002 and 2004, the contents of porn films changed rapidly to contain stronger stimuli (Ogiue 2011). During this period, there was hardly any social debate or criticism on pornography. Instead, the conservative forces of the Tokyo local government and the ruling party strongly criticized the detailed sex education at a certain school as “exceeding sex education” and cut back considerably on sex education.

The porn film producers introduced stronger stimuli for male users, and adult films adopted a stronger, male-centered viewpoint. In Japan, men overwhelmingly watch porn alone and seldom with a partner. Therefore, the film contents tend to adopt a single perspective, incorporating male values. Sexual violence such as rape (Weeks 2011) has become second nature in film scenarios. In the extreme films, the actresses react sexually while being raped; the actresses respond sexually to any objects, or even small living animals, inserted into their vaginas. Actresses just carry out the director’s instructions.14 Yet these depictions, which are far removed from the reality of a woman’s mind and body, give males serious misunderstandings about women’s sexuality. They create a firm belief in men’s minds that women are just tools (Spracklen 2015, 184). Zimbaldo and Coulombe state, “We think the negative effects of excessive, socially isolated porn use are worse for young people who have never had real-life sexual encounters,” because they come to regard sex as simply the mechanical movement of body parts (Zimbaldo & Coulombe 2015, 30). This observation is true of Japanese young people.

Moreover, there has been almost no social criticism of or education on adult films in Japan. Feminists have also ignored pornography and not criticized it. As many people watch pornography in secret, they hesitate to discuss it in public. Therefore, pornography has not become an issue in social discourse or academic research, and it remains a taboo subject.

It has been established that a significant number of actresses who have appeared in porn films were extorted. Young, naive women were deceived and forced into contracts. They were threatened with huge monetary penalties and appeared in the films unwillingly. Many were exposed to sexual violence and also suffered from the limitless spread of their porn pictures and films worldwide on the Internet. These serious human rights violations, and the damage to the minds and bodies of women, were finally recognized as a social problem in 2016 (Miyamoto 2016; Nakamura 2017). Setsuko Miyamoto, a member of “Group for the Awareness of Pornography Damage and Sexual Violence,” supported by about 200 women, stated: “Human philosophy has not caught up with the evolution of technology” (Nakamura 2017). International human rights organization Human Rights Now also addressed this problem (Human Rights Now 2016), and the government strengthened monitoring. Many organizers in this industry have been arrested. The situation in the porn industry has become in the danger of survival, but since anyone can download or upload porn films, even if the films on the Internet are evidence of human rights violations and a source of suffering of former actresses, no one can erase them.

Many men use these adult films as training for sex. In a JASE survey in 2011, 14.9% of male high school students and 40.7% of male university students responded that they learned about sex from adult films (JASE 2013). Men also unconsciously internalize the sensibilities and values of the porn films.15

Young men’s minds and bodies were transported into the world of porn films, whose contents became hard and violent to women in the 2000s, and this had significant effects on actual sex experiences. In adult films, women easily give men the pleasure they desire. But real women often show more reluctance to have sex, may feel pain, and may even say no. Most men do not know how to deal with this kind of reaction in real life. Most Japanese couples do not communicate enough about their desires. As a result, many men have concluded that they do not need real sex if they can watch pornography. Thus pornography has been supplanting real sex in Japan. Not a few women complain to advice websites that their male partners are watching pornography secretly, in their absence.

Introducing the research in the fields of physiology and psychology on how heavy usage of online pornography affects humans will clarify the mechanism of these phenomena. Zimbardo and Coulombe, using the term “enchantment of technology,” summarize the latest research results (Zimbardo and Coulombe 2015. Ch.11) The most powerful sexual organ, the brain, undergoes physiological change through excessive pornography usage. Some changes resemble those of drug addiction. Initially, the stimulation from porn causes dopamine to be secreted and causes erections. But as one’s brain becomes accustomed to the stimulation, the amount of dopamine decreases, requiring newer forms of stimulation.

As the shocking and exciting stimuli continue to be offered online, it can be difficult to notice the onset of sexual dysfunction. As time passes, erections cannot be maintained without the stimulation of porn, and reaching ejaculation becomes more difficult. Research by the Max Plank Institute for Human Development found that porn usage is also related to the reduction of gray matter in the area related to brain-reward sensitivity. As gray matter decreases, both dopamine and dopamine receptors are reduced. Thus it is thought that more and more stimulation is needed to achieve erection through sexual stimuli (Zimbardo and Coulombe 2015). We hope this ongoing research and new, related research will develop greatly and that the results will become public knowledge.

Next, we look at the consequences of online pornography for women. Pornography reduces women’s chance of experiencing pleasure. As I teach at a university, I often hear female students complaining that their boyfriends want to imitate porn films. They all say they experience pain because their boyfriends are too rough with them. Even if the young men refrain from imitating the extreme techniques of pornography, they do not understand women’s unique “sexual response cycle” (Balon and Segraves 2009). The women get no pleasure, and so they lose interest in having sex.

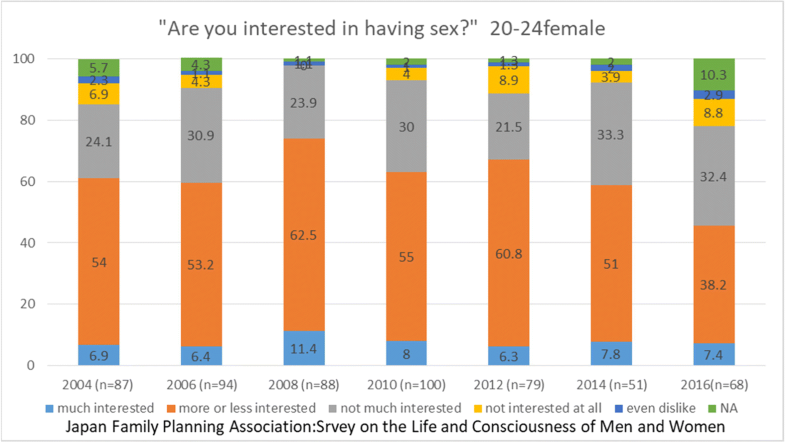

According to the nationwide survey (JFPA 2017), women’s interest in having sex was reported as follows (Fig. 5). For women aged 20–24, although the reason for the increase and decrease of the “not applicable” category is unknown, since 2008 the proportion of those “more or less interested” gradually decreased and that of those “not much interested + not interested at all” gradually increased. No detailed investigations of the change have been caried out yet. However, we hypothesize that the decline of women’s interest in having sex is related to men’s pornography use.

Fig. 5

Clear trends cannot be seen, but 20-24 women who are not interested in having sex increased gradually since 2008

We cannot determine the precise number of porn videos produced or downloaded in Japan per year, but about 10,000 films are said to be produced every year, and 3000 women debut as porn actresses every year (Ogiue 2011). However, because so many porn videos can be viewed for free, the market size has shrunk to approximately 50 to 60 billion yen in 2017, a mere one-fifth the size of the market circa 2000. The industry has continued to reduce costs, but the market is now struggling to survive.

We must also note that an increasing number of young men as well as young women do not watch porn. The nationwide survey by JASE investigated the experience of “watching adult videos” in 1999 and the experience of “watching adult videos” and “viewing adult sites on the Internet” in 2005 and 2011. With the spread of the Internet, porn media shifted from rental DVDs or DVDs on sale (or DVD borrowed from friends) to the Internet. However, in 2011, when the Internet had vastly expanded and Internet porn completely overshadowed DVD porn, 78.8% of male university students “viewed adult sites on the Internet.” In 1999, 92.2% of male university students had “watched adult videos.” In 12 years, the percentage decreased by 13.4%, as Internet use spread.

The decrease is even greater among female university students. In 1999, 50.3% “watched adult videos,” and in 2011, 23.6% “viewed adult sites on the Internet,” a decline of 26.7%. In 1999, most adult videos had softer and less violent content, but since 2011, the content has become harder and more violent, so we can suppose that the women gave up on viewing them.16

Interestingly, analyzing17 the relationship between not viewing porn and one’s image of sex, it is found that not viewing porn is only weakly connected with a negative image of sex as “not fun” and “dirty” among junior high school and high school students, both male and female, and who have no sex experience, almost in common with the 1999, 2005, and 2011 surveys (Harihara 2018, 117–122). Although we do not know the reasons for this result, we can suppose that online pornography is shocking and unacceptable for some young people, and so they avoid viewing it, maintain a negative image of sex, and keep their distance from it.

Further research is needed18 on the reasons why people might avoid pornography. Some men might hate the violent and male-centered content. Alternately, a certain type of man might pour their libido into the characters in animations, games, and so on, which we will investigate in the next section.

2.5 Fantasy World of Otaku Entertainment

Those who indulge in distinctive and captivating entertainment such as animations, manga, and games are called otaku. Otaku culture dates back to the 1970s. The early 1980s saw the emergence of people and a culture obsessed with female characters. The drawing style of sexual comics underwent a dramatic change around 1983, transitioning from photo-like realistic depictions to totally new symbolic representations in animation and manga. Thus a new form of symbolic eroticism was introduced (Otsuka 2004). Afterwards, in the 1990s, the audience increased to form a large social group. Animation producers received their feedback and created a world of characters with sexual appeal, loved by the otaku people.

Otaku people are diverse, and the community has evolved over time. Therefore the definition of otaku and the characteristics of otaku culture have been discussed at length (Tagawa 2009). We support the view of psychiatrist Tamaki Saito, who defines otaku people by their specificity of sexuality (Saito 2006). There are various types of otaku based on many genres of otaku culture, but this paper focuses on the people who obsess over female characters in animations, manga, and games.

Those who are captivated by the charm of female characters can never touch their beloved character in real life. Therefore, they enjoy watching her figure in the works, imagining her, purchasing her merchandise, drawing her, and writing stories about her to express their affection. Loving a character who can never be directly touched is called moe and is said to be similar to one’s first love. Therefore, all female characters that are the targets of moe have an immature appearance (Hotta 2005). Since pure otaku men are virgins themselves, they want their ideal women to be virgins as well (Nakamura 2015a, b).

The rapid spread of the DVD, which arrived on the market in 1996, coincided with the increase in the number of men infatuated with female anime characters. CGI technology also continued to improve, and the figures of female characters were more precisely drawn, enhancing their appeal.

As for computer games, the first love-simulation game was released in 1994, and gained great popularity at once. Since then, many otaku people’s hearts were captivated by love-simulation games.19 In games (Fig. 6), they were able to face the beautiful girl character from the viewpoint of the player, listen to her story, and be her partner. The players are more deeply involved in romance in games than in animations and mangas.20 They are immersed in romance that they perceive as mutual but which is really only their internal dialog (Hotta 2005). Otaku men love a two-dimensional character, not a real living person: this type of romance is called brain romance, and it can still result in sexual arousal. Since they are indifferent to romantic encounters with people, they are clumsy about human relationships, and they generally do not care about their appearance. Some otaku men own dolls shaped exactly like the female characters, or caress pillows with her figure printed on it (Fig. 7). Some decorate their bedrooms with all kinds of goods featuring their beloved characters (Fig. 8).

Fig. 6

Online RPG for smart phone “Alternative Girls” (2016) (Appliv Alternative Girls)

Fig. 7

Pillow cover the character is printed on both sides

Fig. 8

A certain Otaku’s room decorated with goods of the character

Among a broad variety of beautiful-girl games, there are also pornographic games. In them, baby-face characters offer a variety of sexual acts, depending on the gamers’ operations. The gamers can be intensely immersed in this world, unlike real-world sex, which depends on mutuality. Therefore, young men with little sexual experience, once drawn into this world, hardly ever escape from it.

Otaku culture has commonly been seen as an escape for people who dropped out from real romance, and it is often made fun of. Even from our point of view, at first glance otaku entertainment seems to be a simple cause of sexual depression. However, the dynamics of otaku entertainment are very complicated, including elements that suggest that its adherents have a happier approach to sexuality. It is necessary to look more carefully at the various elements of otaku entertainment concerning sexuality.

Koki Azuma, an influential author who notes the significance of otaku culture, argues that girl games function just like Bildungsroman to the young males. These games “emphasize pseudo-life experiences, and players encounter their partners, have romance, experience setbacks and become adult men through game play” (Azuma 2007, 311). As we observe from the outside, we should not overlook the growth that otaku men experience internally.

Mitsunari Oizumi has engaged in participant observation of otaku for over 10 years as (originally) a non-otaku person and has revealed the complex mental dynamics of otaku. In his interpretion, the otaku man is in love with beautiful girl characters because he not only “longs for femininity” but also “hates masculinity.” Otaku men cannot tolerate men’s sexuality being violent and harmful. He repeatedly describes otaku men as kind and gentle. Oizumi states, further applying Jungian psychology, that otaku men’s love of female characters is just a way of integrating “anima” into themselves, which brings them psychological maturity (Oizumi 2017).

In the previous section, we discussed the male-centered extreme content of Japanese online porn films and the growing number of young people who do not use porn. If the young men who do not use porn are otaku men who dislike violent masculinity, their motivation is natural and seems to indicate a positive, more humane approach to sexuality. Here we have an interesting question. Is it possible to realize this more humane sexuality not only in the brains of otaku men but in real relationships? To answer this question, we have to consider the formation process of otaku sexuality in personal development, and the historical shift of otaku.

Hibiki Okura (2011) interviewed otaku men who were born around 1980, probing how their sexuality was formed, dating back to their adolescent experiences. According to Okura, otaku men can be divided into two types. One type of otaku man made comments such as: “It is probably more fun to have a girlfriend, but I have never made a real effort to have a girlfriend, so I do not want one so much.” “I am not very interested in romance.” “Masturbation is good enough.” They have little, if any, motivation for real romance and sex; they value these less than their otaku hobby. In other words, they do not “escape from reality” but have only a slight interest in reality.

The other type of otaku men stated: “I wanted to have a girlfriend, but I missed the chance in my high school days.” “I want a girlfriend, but I still want to keep my hobby following female characters.” These men try to hide their preference for female characters, try to have relationships with women, or try to balance Internet games and real love relationships. According to this research, the difference between these two types is influenced by whether they had already become otaku or they had lived outside otaku culture in adolescence, during which adult sexuality is formed. Those who spent their adolescence outside of otaku culture were able to share feelings and experiences about the reality of love and sex among friends of the same age and sex. In this analysis, sharing experiences with friends is found to lead to motivation and learning techniques of love. On the other hand, people who had already become familiar with otaku culture in adolescence were keenly focused on the topics and activities of animations and games among their friends, and did not talk about real romance or sex at all (Okura 2011). This result suggests that there must be a critical period in personal development concerning the formation of sexuality of otaku.

Otaku people and culture were transformed in the 2000s, in two periods (Harada 2015). The first period was from 2000 to 2005, in which DVDs spread and CGI quality improved greatly. The precise depiction of the female characters led to the blossoming of moe culture. With the development of the Internet, in the latter half of the first period, the media for distributing animations shifted from DVDs to the Internet. As a result, otaku men gained social connections and gathered at events in the cities. Otaku women also emerged as a group and gathered in the city.21

The second period started in the latter half of the 2000s. The values and behavior of otaku culture became “lighter,” and the boundary between ordinary people and otaku diminished. At the same time, animations, manga, and games became quite popular hobbies. Otaku culture was gaining not only a nationwide but a worldwide reputation. The Tokyo neighborhood of Akihabara, the geographic center of otaku culture, was transformed by a new railway opening (in 2005) into a sightseeing spot with a familiar atmosphere that anyone can visit. A high capacity and influencial file-posting website called Nico Nico Movie opened in 2008, incorporating the colors of otaku culture, and rapidly became popular among young people. The idol girl group AKB48, which made their debut at a private theater in Akihabara in May 2005, also gained popularity as national idols, not just local otaku idols. The group deliberately focuses on physical proximity to, or direct contact, with their fans, in the Internet and digital media age.

Some parts of otaku culture have gone from subcultures to the mainstream in Japan since the latter half of the 2000s (Harada 2015). The surveys conducted in 1990, 2005, 2009, and 2015 in two spots (Suginami city in Tokyo and the regional city of Matsuyama in Ehime Prefecture), targeting 20-year-old men and women, show that the percentage of people choosing “comics, animation, games, idle chasing” as their “most important hobby” increased consistently in both cities over the years. The combined rate was just 2.7% in 1990, but it increased to 10.5%, 10.4%, and 20.6% in Suginami and to 14.8%, 16.0%, and 24.9% in Matsuyama in 2005, 2009, and 2015, respectively. Clearly, otaku culture has broadly expanded. However, those who are strongly attracted to female characters are only one part of the picture. In the same survey, people who “had something like otaku”—light otaku—comprised only 13.4% in 1990 and increased to 46.8%, 59.4%, and 53.3% in Suginami and to 36.0%, 50.0%, and 53.3% in Matsuyama. In both spots, rates consistently increased, and the gap between Tokyo and the local city disappeared. Today, in 2015, more than half of 20-year-old men and women are attracted to otaku culture, including the “light” preference (Tsuji et al. 2016).

Light otaku people are not unsociable or poor communicators, and some of them have romantic and sexual relationships with real-life partners (Harada 2015). However, if they are attracted by romance and sex in two-dimensional games or animations, they no longer concentrate solely on real-life relationships. In practice, the virtual love of an animation character and the love of a real person inevitably exclude each other, creating a conflict. The advertisement for the game “Alternative Girls” states: “This game is prohibited for the person who has a real girlfriend” (Appliv-Alternative Girls), suggesting that the game is so engrossing that it might cause someone to lose his real-life girlfriend. In general, otaku men who want real-life girlfriends have two strategies. One is to find women who understand their otaku preference, and the other is to have girlfriends and hide their otaku preference from them (Harada 2015). The former strategy is hardly likely to succeed, and the latter is not easy to pursue, as their preference is likely to be exposed sooner or later.22 Nonetheless, it seems that the dichotomy of the real world/romance/sexuality versus the virtual world/romance/sexuality actually has become quite weak as otaku culture has become less intense.

Otaku sexuality has changed drastically, as we see. Today otaku culture has become less intense, and otaku men have greater possibilities of having girlfriends. As we mentioned above, some otaku men hate violent and harmful masculinity and take a more gentle approach. Now we would like to consider again what possibilities there are to realize sexuality with a more gentle approach to relationships. We think that this is possible and indeed that this is potentially one way to break through the difficulties of current Japanese sexuality. The reason why otaku men hate masculinity so much is thought to be that the society is full of violent male-centered pornography. So if social discourse on pornography increases and people do not fall under its spell, harmful pornography will lose its power, and the otaku hatred of masculinity will also fade.

Although these possibilities cannot be denied, it may take a very long time before we see evidence of a halt to today’s sexual decline.

3 Conclusion

We have given a brief overview of the multifaceted interplay of information technology and the sexuality of youth in Japan since 2000. This topic has seldom been considered in academic studies in Japan. Few investigations or surveys have been conducted on this topic. Therefore, what we have done in this paper is something like placing the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle on a surface. The overall picture may be seen vaguely but a little better, while we realize which parts we cannot yet see. In this last section, we will grasp more thoroughly our overall picture. Then we will discuss the hypothesis of other probable factors of sexual depression and also about the solutions. At the end, we would like to point out important topics for future research in the field of the relationship between digital technology and sexuality.

Since 2000, developments in Internet and digital technology have given people access to two vast domains of sexual entertainment. One is online porn films, and the other is entertainment based on romance in animations and games. The thriving of these two forms of entertainment is, in our opinion, the biggest cause of sexual depression in Japan since the mid-2000s. Pornography is designed for men, with a completely male-centered vision, offering unrealistic and extreme stimuli. Under this influence, both men and women have experienced more difficulties in having sex. Entertainment based on the romance of animations and games has a more complicated interplay with men’s sexuality.

Physiologically speaking, for men the brain is where an erection begins, so male sexuality is susceptible to visual-brain stimulation. Male brains could also more easily become dependent on the Internet and digital media than female brains (Zimbardo and Coulombe 2015). This physiological mechanism will help us understand how this new technology is causing a major change in male sexuality.

This change coincided with deteriorating employment and economic conditions for young people, who have lost confidence in life, are anxious about the future, and are afraid of failing at everything. Many of them have lost interest in the rich and profound world of romance and sex, given the severe conditions of a stressful life. At the same time, a fantasy world blossomed online. The numbers of young men attracted to this fantasy world increased, and many turned their backs on real romance and sex.23

In Japan, the Internet has also been used extensively for compensated dating, prostitution, and sexual services. In Japan, Internet sites advertising sexual services, in addition to pornography sites, became enormous. Websites of sexual service businesses are esthetically pleasing, alluring, voluminous, high-budget productions. Their messages can be found everywhere, in dating sites and applications, in SNS, and in personal mail, and their impact is thought to be significant. Men who are frequently exposed to these promotions will have misunderstandings about women. Women who do the same will become indifferent to having sex and will hate sex. As a result, men have relied more on pornography, and more women have become indifferent to sex and developed a negative impression of it. It could be said that a vicious circle has been formed.

There must be some other factors responsible for sexual depression. Below we present some hypotheses.

As Zimbaldo points out, Internet technology has brought about big changes, especially to males. But I hypothesize that this technology has also had an effect on women. I would like to examine the hypothesis in future research. Since the mid-2000s, women have increasingly been expressing negative impressions of sex, such as that it is “not fun” or “not beautiful” (Harihara 2018). The reasons for this are not yet clear. Are young women afraid of sex because of extreme porn images, or is the gap between female fantasy and male fantasy too large? Or is it because men tend to imitate porn? If the details are realized, the whole picture of how new technology makes sex difficult will be more clearly drawn.

Sexual depression among youth in Japan is not always recognized as a problem, and some people are satisfied with the current situation, but many young people are suffering from the situation and seeking escape. They will be interested in considering the following solutions. Sexual depression occurs within a complicated framework, so finding the solutions is not simple. We will summarize our four recommendations below.

The first recommendation is to introduce wide-scale comprehensive sex education. Many people in Japan still conflate sexuality with pornography or sex services, so many resist sex education, imagining that it incorporates pornography into education. However, Japanese people have been only passively exposed to the change to sexuality brought about by new technologies, because people do not have the basic knowledge and ideas to take charge of their own sexuality. Comprehensive sex education for each age group, from children to the elderly, is the most important solution.

The second recommendation is to boost social discourse on sexuality. In contemporary Japan, sexuality-related media are mostly divided into men’s media and women’s media. It is necessary to discuss many issues of sexuality such as pornography, sexual services, and sexual games in forums of social discourse open to everyone, regardless of gender.

The third recommendation is to encourage more professional research and investigation on sexuality. In Japan, issues of sexuality have been made taboo, not only in sociology but also in other academic fields, such as medicine, psychology, physiology, history, and cultural anthropology. Academic research is necessary to support the first and second points above.

Fourth, concerning online pornography, rather than trying to regulate it, it would be better if the public could gain scientific knowledge of what kind of use of porn affects human sexual consciousness and sexual behavior, and knowledge about real sex. In this way, they could better control their own use. The activities of groups such as MakeLoveNotPorn (MakeLoveNotPorn.tv), created by Cindy Gallop, should be carried out in Japan as well.

Technology itself cannot decide the situation of sexuality in any sense. What happens instead is that specific forms of technology meet specific situations of sexuality, and they interact in specific economic, social, and cultural contexts. As a result, the forms of technology and the situations of sexuality are transformed. In other societies, the forms of technology, the situation of sexuality, and all the economic, social, and cultural contexts would be quite different from what we see in this paper. We can point out some specific features of Japan in this regard. The fact that many women got involved in compensated dating and that the sexual service business surfaced in society has much to do with the Japanese-specific social context, which had a great impact on the interplay of information technology and sexuality in Japan. The fact that the young generation were living in dire conditions has to do with a specific economic context, which led young people who were easily depressed into a fun-filled fantasy world of romance. However, what the specific forms of technology are, what the specific situations of sexuality are, and what the specific contexts are, are not made clear. Cross-cultural comparative research in global leisure studies on information technology and sexuality is needed to identify these specific features.

Footnotes

- 1.

The growth of the Internet is believed to have impacted the sexual behavior of various sexual minorities by dramatically promoting mutual communication among them. Unfortunately, because research data on these minorities is lacking, we must limit our study to the heterosexual majority.

- 2.

In 1994, the Japan Society of Sexual Science defined “sexless” in the following way: “Although specific reasons such as illness are not recognized, a couple who has not had consensual intercourse or sexual contact for more than 1 month, and who is not expected to do so for a long time to come” (JSSS Defenition of the term “sexless”).

- 3.

Survey data is lacking, but extramarital sex is said to have also increased (Araki et al. 2016).

- 4.

Marriage for love became mainstream in Japan by the 1980s, and in the 1990s it became common to follow a life path of getting married after having a number of love relationships that included sex. Thus young people today who have no dating or sexual experience are very unlikely to get married or to become parents.

- 5.

Unlike in many societies in the West, finding a partner is not considered a must in Japan. Changes in modern Japanese society are making it more and more convenient to stay single.

- 6.

In this paper, the term “university” includes four-year colleges.

- 7.

- 8.

The heavy user of PCs is defined as “a person who uses PC for more than 2 hours on holidays.” Thirty-three percent of female and 36% of male university students were heavy users (JASE 2007, 60).

- 9.

Until around 2005, PCs were generally bulky units such as desktops, and heavy users of PCs had to sit at their desks for a long time. People who could tolerate it became heavy users of PCs and therefore became more inactive, and people who could not bear it used mobiles and remained active. Thus the device’s characteristics caused a division in lifestyles in this period, stemming from people’s personal characteristics. The introduction of lighter PCs and the spread of wifi in the latter half of the 2000s ended this polarization.

- 10.

This description of the romance boom and vigorous sexual activities demonstrates that the contemporary Japanese sexual depression cannot be explained by factors such as Japanese social structure or the communication style of the Japanese.

- 11.

Prostitution in Japan has historically thrived (Koyano 2007).In the pre-modern era, brothels were considered a dream world, and prostitutes who were sold from poor families were never looked down on. As modernization brought Western norms of sexuality, disdain toward prostitutes spread among the people. However, more recently, a more tolerant attitude toward prostitution has resurfaced among young people.

- 12.

In the next survey in 2011, no questions about dating sites were asked. Therefore, the shift in rates cannot be observed.

- 13.

Despite the flood of pornography, there have only been a few scientific investigations of pornography viewing behavior in Japan. This description of the changes in pornography viewing behavior relies on the author’s observations in everyday social life.

- 14.

A famous porn star confessed after her retirement, “I felt nothing when I was working for the films. Nothing…. No feeling like fun or pleasure…. I just did what a porn actress should do” (Nakamura 2017).

- 15.

Akane Hotaru, a retired porn actress, has launched a social campaign stating “Don’t imitate porn films” and offers sexual consultations for women.

- 16.

Since the mid-2010s, adult films for women began to be made in Japan, and viewing behavior may have changed, though no survey has been done on the topic.

- 17.

Harihara uses a method of hierarchical multiple regression analysis.

- 18.

Academic and scientific research is sorely needed on the pornography viewing behavior and the sexual consciousness or sexual behavior of people in Japan. Furthermore, Japanese porn films have flooded the Chinese and other Asian markets and profoundly impact the sexual consciousness and behavior of Asian youth (Nakamura 2015). In these countries, research on sexuality is just as underdeveloped as in Japan, and people’s sexual consciousness may change drastically without being accurately observed in academics and science. We think it necessary to investigate and research what is happening in relation to digital technology, the Internet, and sexuality in other Asian countries as well.

- 19.

They are also called beautiful-girl games, or moe games.

- 20.

The new games in 2018 can be played with a VR apparatus. The involvement will be much deeper. See the public site of “Alternative Girls 2.” (Alternative Girls2 Public site)

- 21.

The sexuality of female otaku is also an important topic. However, we will deal with this in another paper because of space limitations.

- 22.

On advice sites, women sometimes write in, saying they are shocked to find their husbands or boyfriends’ secret adult games or images of anime characters in sexy positions, and they do not know how to deal with it. We wonder if the men could be considered to be cheating.

- 23.

In Canada and the United States, subcultures of young men called incels (involuntary celibates) and MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way) are spreading. They set themselves in opposition to a society supposedly biased toward women. A few may take revenge on women. Meanwhile, Japanese young people who are satisfied with the fantasy world without real partners can be regarded as more mentally stable. A cross-cultural comparative study should be done.

Notes

References

-

Alternative Girls2 Public site. https://lp.alterna.amebagames.com/. Accessed 18 Aug 2018.

-

Appliv Alternative Girls. https://app-liv.jp/1100088261/. Accessed 18 Aug 2018.

-

Araki, C., Ishida, M., & Okawa, R. (2016). Sekkusuresu Jidai no Chukonen Sei Hakusyo. Harunosora.Google Scholar

-

Asano, T. (2006). Wakamono no Genzai. In T. Asano (Ed.), Kensyo: Wakamono no Henbou. Keiso Shobo.Google Scholar

-

Attwood, F. (2018). Sex media. Polity.Google Scholar

-

Azuma, K. (2007). Gehmu teki Riarizumu no Tanjou. Kodansya.Google Scholar

-

Balon, R., & Segraves, R. T. (2009). Clinical manual of sexual disorder. American Psychiatric Publishing.Google Scholar

-

Cabinet Office Survey on Marriage and Family Forming (2011). http://www8.cao.go.jp/shoushi/shoushika/research/cyousa22/marriage_family/pdf/gaiyo/press.pdf. Accessed 10 Aug 2018.

-

Enda, K. (2001). Darega Dareni Nani-wo Urunoka. Kansei Gakuin University.Google Scholar

-

Fujiki, T. (2009). Adaruto Bideo Kakumei shi. Gentousha.Google Scholar

-

Futakata, R. (2006). Medhia to Wakamono no Konnichiteki Tsukiaikata. In T. Asano (Ed.), Kensyo: Wakamono no Henbou. Keiso Shobo.Google Scholar

-

Genda, Y. (2010). Ningen ni Kaku wa Nai. Minerva Shobo.Google Scholar

-

Genda, Y., & Saito, J. (2007). Shigoto to Sex no Aida. Asahi Shinbun.Google Scholar

-

Harada, Y. (2015). Shin Otaku Keizai. Asahi Shinbun.Google Scholar

-

Harihara, M. (2018). Sei ni Taisuru Hiteiteki Image no Zouka to Sono Haikei. In Y. Hayashi (Ed.), Seishonen no Sekoudou wa Dou Kawatte Kitaka. Minerva Shobo.Google Scholar

-

Hekma, G., & Giami, A. (2014). Sexual revolutions. Palgrave.Google Scholar

-

Honda, T. (2005). Moeru Otoko. Chikuma Shobo.Google Scholar

-

Hotta, J. (2005). Moe Moe Japan. Kodansha.Google Scholar

-

Human Rights Now (2016). Research Report on Human Rights Abuses Against Girls and Women by Pornography: Adult Video Industry. http://hrn.or.jp/news/6600/. Accessed 25 Aug 2018.

-

JAFP (Japan Association of Family Planning). (2017). Dai 8 kai Danjo no Seikatu to Ishiki ni Kansuru Chosa Hokokusyo. In JAFP.Google Scholar

-

JASE (Ed.). (2007). Wakamono no Sei Hakusyo Dai 6 kai Chosa Hokokusyo. Shogakukan.Google Scholar

-

JASE (Ed.). (2013). Wakamono no Sei Hakusho Dai 7 kai Chosa Hokokusyo. Shogakukan.Google Scholar

-

JASE. (2018). Seishonen no Seikoudou Dai 8 kai Chosa Hokokusyo. JASE.Google Scholar

-

JSSS (Japan Society of Sexual Sciences) Definition of the term “sexless”. http://www14.plala.or.jp/jsss/counseling/sexless.html. Accessed 30 Aug 2018.

-

Katase, K. (2018). 21seiki ni okeru Shinmitsusei no Henyo. In Y. Hayashi (Ed.), Seishonen no Sekoudou wa Dou Kawatte Kitaka. Minerva Shobo.Google Scholar

-

Kon, I. (2001). Deai-kei Jidai no Renai Shakaigaku. Best Shinsho.Google Scholar

-

Koyano, A. (2007). Nihon Baisyun Shi. Shinchosha.Google Scholar

-

Kumazawa, M. (2018). Karoushi/Karoujisatu no Gendai shi. Iwanami.Google Scholar

-

MakeLoveNotPorn.tv. https://makelovenotporn.tv/pages/about/how_this_works. Accessed 15 Nov 2018.

-

Miyamoto, S. (2016). AV Shutsuen wo Kyouyousareta Kanojotati. Chikuma Shobo.Google Scholar

-

Nakamura, A. (2014). Nippon no Fuzokujo. Shinchosha.Google Scholar

-

Nakamura, A. (2015a). AV business no Shogeki. Shogakkan.Google Scholar

-

Nakamura, A. (2015b). Repos Chunen Dotei. Gentosha.Google Scholar

-

Nakamura, A. (2017). AV Joyu Syometsu. Gentosha.Google Scholar

-

Nakashio, C. (2016). Fuzokujo toiu ikikata. Kobunsha.Google Scholar

-

National Institute of Population and Social Security Research: The Basic Survey on Birth Trends. http://www.ipss.go.jp/site-ad/index_Japanese/shussho-index.html. Accessed 25 Aug 2018.

-

NHK Nihonjinno sei purojekuto. (2002). Ninohjinno seikoudou/seiisiki NHK Syuppan.Google Scholar

-

Nito, Y. (2014). Joshikousei no Ura Shakai. Kobunsha.Google Scholar

-

Ogiue, C. (2011). Sex media 30 nen Shi. Chikuma Shobo.Google Scholar

-

Oizumi, M. (2017). Otaku Towa Nanika? So Shisha.Google Scholar

-

Okubo, Y., Hataya, K., & Omiya, T. (2006). 30dai Mikon Otoko. NHK Shuppan.Google Scholar

-

Okura, H. (2011). Gendai Nihon ni okeru Jakunen Dansei no Sexuality Keisei nitsuite. Sociological Reflections, 32 Tokyo Metropolitan University.Google Scholar

-

Otsuka, E. (2004). Otaku no Seishin shi -80nendai ron. Kodansha.Google Scholar

-

Pacher, A. (2018). Sexlessness among contemporary Japanese couples. In A. Beniwal, R. Jain, & K. Spracklen (Eds.), Global leisure and the struggle for a better world: Leisure studies in a global era. Palgrave.Google Scholar

-

Rakuten O-net (Marriage Partner Introduction Service Rakuten O-net) (2018) Survey on the Consciousness of Romance and Marriage of People Aged 20. https://prtimes.jp/main/html/rd/p/000000064.000022091.html. Accessed 10 Jul 2018.

-

Saito, T. (2006). Sento Bisyojo no Seishin Bunseki. Chikuma Shobo.Google Scholar

-

Sato, T., & Nagai, A. (2010). Kekkon no Kabe. Keiso Shobo.Google Scholar

-

Spracklen, K. (2015). Digital leisure, the internet and popular culture: Communities and identities in a digital age. Palgrave.Google Scholar

-

Tagawa, T. (2009). Otaku Bunseki no Houkousei. In Nagoya Bunridai Kiyou (Vol. 9). Nagoya Bunridai.Google Scholar

-

Takahashi, M. (2007). Communication Media to Seikoudou niokeru Seishonen no Bunkyokuka. In JASE (Ed.), Wakamomo no Sei Hakusho. Shogakukan.Google Scholar

-

Tanimoto, N. (2008). Renai no Shakaigaku. Seikyusha.Google Scholar

-

Tsuchida, Y. (2018). Sei ya Renai ni Syokyokuteki na Wakamono. In Y. Hayashi (Ed.), Seishonen no Sekoudou wa Dou Kawatte Kitaka. Minerva Shobo.Google Scholar

-

Tsuji, I., Okura, H., & Nomura, Y. (2016). Wakamono Bunka wa 25 nenkan de dou Kawatta ka. In Bungakubu Kiyou Shakaigaku Johoshakaigaku (Vol. 27). Chuo University.Google Scholar

-

Turkle, S. (2012). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other. Basic Books.Google Scholar

-

Ushikubo, M. (2015). Renai Shinai Wakamonotachi. Discover, 21.Google Scholar

-

Weeks, J. (2007). The world we have won. Routledge.Google Scholar

-

Weeks, J. (2011). The languages of sexuality. Routledge.Google Scholar

-

Yamada, M. (1996). Kekkon no Syakaigaku. Maruzen.Google Scholar

-

Zimbardo, P., & Coulombe, N. (2015). Man (dis)connected. Rider.Google Scholar