Introduction

Research regarding problematic sexual behaviors and problematic pornography use is advancing quickly.1 Various research groups have proposed a variety of models that purportedly account for some or all aspects of such behaviors.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 However, attempts at empirical evaluation of the models have generally been meager and unsubstantial. Regrettably, this criticism of the field is not novel. This state of affairs has persisted for many years and was noticed and stressed much earlier in the development of the field, for example, by Gold and Heffner.8 However, after more than 20 years, the problem still exists and has been critiqued by researchers, for example, by Gola and Potenza9,10 or Prause.11

One plausible explanation for this lack of empirical rigor in evaluating models of such behaviors is that current models are most often derived post hoc from either narrative reviews (mostly nonsystematic) of multiple studies (refer to the study by Walton et al5 and Brand et al12) or via systematic reviews and meta-analyses of narrow bands of literature (refer to the study by Grubbs et al3). Attempts at comprehensive empirical validations of the models after they have been proposed are rare, resulting in a proliferation of proposed models but a dearth of empirically validated models. In turn, this leaves the field in a state of perpetual discussion about the validity or superiority of one model over another, without sufficient evidence to substantively support any one particular view. In our view, this is a crucial obstacle to advancement of the research field of problematic sexual behaviors. Moreover, this drawback is especially poignant now, as compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) was included in the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases,13,14 despite vociferous objections regarding the status of its scientific foundations.15

One of the most recently proposed models is the Pornography Problems Due to Moral Incongruence model (PPMI model3), which received very significant attention from researchers upon its publication.3,16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 The PPMI model depicts pornography-related problems as stemming from 3 groups of factors: (i) individual differences in affect regulation and impulse control (eg, high impulsivity, maladaptive coping strategies, emotional dysregulation), (ii) habits of use (ie, high frequency and/or time dedicated to pornography use), and (iii) moral incongruence regarding pornography use (ie, a conflict between one’s moral beliefs about pornography use and one’s actual behaviors). As the name of the model suggests, moral incongruence-related factors are given special attention within the PPMI model and relations between them are presented in the greatest detail.

Central to the PPMI model is the proposition that among people who use pornography, moral disapproval of such behaviors can contribute to feelings of misalignment between one’s own beliefs, norms, and attitudes on the one side and behavior on the other, that is, moral incongruence. Authors of the model describe moral incongruence as emerging from the interplay of mechanisms that are similar in nature to those proposed by Festinger23 in cognitive dissonance theory. Moreover, research shows that—at least for a significant proportion of people—moral incongruence can stem from religious convictions,24 which is what the model predicts.

In previous research, moral disapproval of pornography use and religiosity were shown to be positively related to self-perceived addiction,25, 26, 27, 28 severity of negative symptoms of pornography addiction,29 or treatment seeking for problematic pornography use30 (for review, refer to the study by Grubbs and Perry24).

The PPMI model is an important contribution to the current literature, as its main point of focus—moral cognition and morality-related variables—is often neglected in other models.

However, despite this focus, the PPMI model is not limited solely to moral incongruence, as other factors that possibly influence sexual behavior and sexual behavior judgments are also accounted for by the model (eg, dysregulation-related individual differences variables). Because of this, the model can be treated as not only a narrow, special purpose framework but also as a more general framework for investigating the structure of the factors influencing pornography-related problems.

Moreover, the model was designed to describe the factors contributing to self-perceived pornography addiction3 and is also based on research predicting self-perceived addiction.3,25,31 However, as the authors of the model suggest that the PPMI model can be a suitable framework for investigating the factors influencing a broader set of behavioral, cognitive, and affective symptoms connected with problematic pornography use and should be examined in this role.

PPMI model With Regard to Self-Perceived Addiction

Self-perception of addiction refers to the conviction of a person that he or she belongs to the group of addicts—this perception is directed by a subjective, folk-psychological definition of what addiction is and what characterizes an addicted person and is therefore often measured by simple, face-valid statements such as “I am addicted to internet pornography”25 or “I would call myself an internet pornography addict.”26 Agreeing with statements like this reflects a cognitive act of self-labeling and often has little to do with formal psychological and psychiatric theories of addiction. However, such self-labels are important as they may lead to self-stigmatization,32 distress, or treatment seeking.3,25 As the way in which “self-perceived addiction” is operationalized has generated some controversy (for a discussion, refer to the study by Brand et al,16 Grubbs et al,26,31 and Fernandez et al33), we propose that it is most clearly operationalized as we have described previously. That is, self-perceived addiction is best described as a mental act of self-inclusion within a group of addicts, the measurement of which is not necessarily based on quantitative self-description of behavioral symptoms (such as frequency of use, difficulty abstaining, emotional distress, using pornography as a coping mechanism, or craving). Such symptoms can reflect clinical, specialized definitions of addiction but do not have to reflect the subjective and personal definition of what characterizes an addict, which can actually have a leading role in behaviors such as treatment seeking.3

PPMI Model With Regard to Problematic Pornography Use

Truly dysregulated pornography use is connected to a fairly complex set of symptoms that are not reflected in simple declarations of being an addict. This set of symptoms is often referred to as “problematic pornography use” and can include: (i) excessive use; (ii) multiple, unsuccessful attempts at limiting pornography use; (iii) pornography craving; (iv) pornography use as a coping strategy to deal with negative emotions; and (v) recurrent engagement in pornography use even when it results in distress or other negative consequences.34 Defined in this way, problematic pornography use reflects psychological and psychiatric theories of dysregulated behavior (also addictive or compulsive behavior) much more closely than simple, subjective self-appraisals of addiction. This more general set of symptoms is also a basis for all declarative methods of assessing pornography-related problems.35 The quantitative description of behavioral, affective, and cognitive factors that these measures are based on calls for at least a degree of objectivity on the part of a respondent and described symptoms may or may not be a part of his orher personal lay definition of addiction. Because of this, such a method of measurement necessarily addresses a different underlying phenomenon than the “I am addicted to pornography” statement. Both of these phenomena are obviously worth investigating. However, they are often interesting for other reasons (subjective definition leading to self-stigmatization vs more formal and reliable description of symptoms more accurately reflecting psychological theories) and should be clearly differentiated between in research on the PPMI model and related research questions as this branch of research develops from its current initial stage. This should bring more much-needed clarity to the field. The present study follows the proposed distinction.

In addition, Grubbs et al3 in their outline of the PPMI model actually indicate that the model should explain broader “pornography problems” and not only self-perceptions of addiction. Taking all of these arguments into consideration, it seems worth investigating whether the PPMI model is suitable to explain both the specific case of self-perceptions of addiction and the broader construct of problematic pornography use. Successful verification of the model in both of these cases would solidify and give strong additional support for the PPMI framework.

Moral Incongruence Vs Moral Disapproval in the PPMI Model and Related Research

There are 2 issues regarding this subject that, in our view, merit additional attention. First, as was mentioned before, in line with the PPMI model, moral incongruence can be significantly motivated by religious convictions. We agree with this argument and think that the line of investigation that can stem from it should be vigorously pursued. However, we also note that the postulated religiosity-moral incongruence relation may have been inflated in prior research by the way in which moral incongruence was often operationalized. In early works on the subject, Grubbs et al36 operationalized this construct with the following 4 statements: “Viewing pornography online troubles my conscience,” “Viewing pornography online violates my religious beliefs,” “I believe viewing pornography online is a sin,” and “I believe that viewing pornography online is morally wrong.” Only the last of the 4 statements does not directly address religious beliefs or use religiously laden terms like “conscience.” In our view, the first 2 of these 4 statements are more accurately described as addressing religious incongruence more than moral incongruence, and references to “conscience” might similarly pull for religiousness. Naturally, the strength of religious convictions is a natural source for this kind of incongruence, but morality, as depicted in the PPMI model, should also be studied outside of the religious context, as it can have potential numerous predictors that are not directly related to religion (eg, political and sociopolitical views).19 Moral disapproval or incongruence should be operationalized in a way that reflects this fact and in a way that is sensitive to a multisource determination of morality.

Second, in some research, especially studies using shorter protocols, moral incongruence is operationalized by just one statement of the 4 described before “I believe that viewing pornography online is morally wrong.”25 As was mentioned, this statement does not directly invoke a religious context, so the concerns delineated previously do not apply to it. However, there is also an additional issue here: these kinds of statements do not accurately appraise moral incongruence, but rather moral disapproval.37 This remark is consistent with some of the earlier works led by Grubbs et al,36,38 in which the label “moral disapproval” was used. The reason is 2 fold: (i) the variable lacks the component of awareness or sensitivity to one’s own behavior transgressing believed norms (refer to the study by Wright22) and (ii) most studies on the relationship between moral incongruence and self-perceived addiction are based on subjects who declare a lifetime exposure to pornography—this is also the case for the present study. Such a restriction still allows for a lot of variability in pornography use. It is possible that subjects who use pornography rarely (eg, once or twice a year, or even with greater frequency) and see pornography use as to some degree morally wrong still do not experience feelings of incongruence because occasional transgressions can be easily ignored. In the most recent work, Grubbs et al37 operationalize moral incongruence as the interaction between moral disapproval and pornography use, which is a significant improvement. However, it addresses the second point delineated previously, but not the first one, as this method of measurement still does not reflect the component of awareness or sensitivity to misalignment between one’s own behavior and norms. As a solution to this situation, within our study, aside from moral disapproval of pornography use, we also measured moral incongruence–related distress (see Materials and Methods section), which is a more direct measure of experiencing misalignment between one’s own norms and behavior and therefore a more accurate measure of moral incongruence. We think that this addition is a necessary extension of the PPMI framework.

Present Study

The first goal of the present study was to provide data and carry out a direct evaluation of the PPMI model. This would be the first such attempt in the available literature. Our evaluation is based on 3 paths through which pornography-related problems can be predicted, based on the model: (i) dysregulation path, (ii) habits of use path, and (iii) moral incongruence path (Figure 1). Although Grubbs et al3 in their initial proposition stressed the presence of paths 1 and 3, in our view, habits of use can be accounted for fully by neither of them (one can imagine high use of pornography that is not the result of dysregulation or moral incongruence), and therefore can be thought of as constituting an additional, separate path (path 2). In our view, this would make the current analysis more clear.

Figure 1

Path analysis evaluating the Pornography Problems Due to Moral Incongruence model (based on a sample of n = 880), proposed by Grubbs et al.3 Self-perceived addiction is placed in the role of main dependent variable. Standardized path coefficients are shown on the arrows (**P < .001, *P < .05). For the sake of readability of the figure, the model does not depict one additional path: moral incongruence–related distress was related to avoidant coping (r = 0.21**).

Path 1

Dysregulation

Following one of the suggestions given by the authors of the model 3, in our analysis, we used maladaptive coping strategies, specifically avoidant coping, as an indicator of dysregulation (path 1). This variable was chosen as previous studies brought initial evidence of a relationship between avoidant coping and problematic sexual behavior.39, 40, 41 In addition, we hypothesized that placing avoidant coping within the model will help to illustrate the possible connections between path 1 (dysregulation) and 3 (moral incongruence), as avoidant coping would be significantly connected to moral incongruence–related distress. We propose that using avoidant coping can be connected with higher levels of distress, which is supported by the rich literature in the domain of health psychology (eg, Herman-Stabl et al,42 Holahan et al,43 and Roth and Cohen44).

Path 2

Habits of use

Frequency of pornography is one of the most popular variables representing the degree of exposure to pornography and was treated as an indicator of habits of use (path 2). Within the PPMI model,3 this variable is also treated as a mediator of influence of other variables (belonging to paths 1 and 3, Figure 1) on self-perceived addiction to pornography, and we follow this conceptualization in our model.

Path 3

Moral Incongruence

As the moral incongruence path is given special attention within the PPMI model, we analyzed the relationships within this path in the greatest detail, using religiosity, moral disapproval of pornography use, and moral incongruence-related distress as indicators (Figure 1). We hypothesized that higher religiosity will contribute to higher levels of moral disapproval of pornography, higher feelings of incongruence between norms and own sexual behavior, as well as be directly, positively connected to self-appraisals of problematic pornography use (refer to the study by Grubbs and Perry24 for a review of evidence, Grubbs et al,26 and Lewczuk et al27). Following the PPMI model, we hypothesized that moral disapproval of pornography use and the frequency of pornography use will both contribute to moral incongruence–related distress. In other words, higher disapproval of pornography use along with higher use itself will contribute to creating incongruence-related distress. Furthermore, in line with the proposition by Grubbs et al25, we hypothesized that moral incongruence–related distress would positively predict self-perceived addiction to pornography. The described design of the model is depicted in Figure 1.

The second goal was to test the validity of the PPMI model not only for self-appraisals of pornography addiction (model 1) but also for problematic pornography use (model 2), which was described in the earlier sections of the Introduction. We predicted that frequency of pornography use will have a higher impact on self-appraisals of pornography addiction than problematic pornography use, and the opposite pattern would be visible for moral incongruence–related distress as well as avoidant coping.

The third goal was to test the validity of the PPMI model in a cultural context other than the United States. We have some findings from outside the United States indicating that the relationship between morality-related variables (eg, religiosity) and symptoms of problematic pornography use can depend on culture.33,45,46 Validating the model in another cultural context is one of the most important research directions, which was demarked by the authors of the model themselves.3,31

Materials and methods

Procedure and Sample

The data were gathered online, through the Pollster research platform (https://pollster.pl/). The participants were asked to fill out a set of measures that were relevant to the study goals. The group of participants was recruited so as to be representative for the Polish population (based on census norms for 2018 for gender and age group and 2017 for the rest of the sociodemographic variables; the norms were provided by Statistics Poland—Polish abbreviation: Główny Urząd Statystyczny). The representative sample consisted of 1036 subjects (refer to the study by Lewczuk et al27). Following previous studies (eg, Grubbs et al25), for the purpose of the current analysis, a subset of participants (n = 880) who declared contact with pornography at least once in their lifetime was selected and was the basis for our analysis. Therefore, the sociodemographic information will be provided below only for this subgroup. The participants in the resulting sample were between 18 and 69 years of age: 44.9% women (n = 395), 55.1% men (n = 485); Mage = 43.69; SD = 14.06.

Education

The respondents’ education was as follows: basic and vocational (27.7%, n = 244), secondary (39.8%, n = 350), and higher (32.5%, n = 286).

Size of the Place of Residence

The place of residence of the respondents was a village (37.6%, n = 331), a town with less than 100,000 inhabitants (32.3%, n = 284), a town with 100,000-499,999 inhabitants (17.8%, n = 157), and a town with more than 500,000 inhabitants (12.3%, n = 108).

Measures

Self-perceived addiction, following other studies in the area,25,26 was measured using one item derived from the Cyber-Pornography Use Inventory-9:47 “I am addicted to pornography.” The answer options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Problematic pornography use was assessed with the Brief Pornography Screener (BPS34), a 5-item scale designed so as to screen for symptoms of problematic usage of pornography. The participants answered on a scale: 1—Never, 2—Sometimes, and 3—Frequently. For the purpose of the analysis, the sum of scores obtained in the BPS items was taken into account (α = .88).

Hypersexual behavior was operationalized through the general score in the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory,48 a 19-item questionnaire measuring symptoms of hypersexual behavior. The answer options ranged from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very often). The sum of the scores obtained in all the items constituted a general score (α = .96).

Dysregulation was indicated by avoidant coping, which was assessed through the Brief COPE questionnaire.49 Brief COPE consists of 28 items and has 14 subscales reflecting different coping strategies. The participants had answer options ranging from 1 (I haven’t been doing this at all) to 4 (I’ve been doing this a lot). Following previous studies (eg, Schnider et al50), we distinguished avoidant coping as a group of 5 strategies: self-distraction, denial, behavioral disengagement, self-blame, and substance use (α = .71).

Habits of pornography use were indicated by frequency of pornography use. Asked about their frequency of pornography use, participants had the option to indicate that they had never had contact with pornography in their lifetime (denoted as 0) or mark one of the options regarding the frequency of pornography use in the last year, from 1 (Never in the last year) to 8 (Once a day or more).

Religiosity was assessed with 3 items used by Grubbs et al25 (“I consider myself religious,” “Being religious is important to me,” and “I attend religious services regularly”). The response scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The sum of the scores obtained for these 3 items was taken into account for the purpose of the analyses (α = .94).

When asked about their religious affiliation, most participants reported being catholic (77.3%), 3.5% declared other religious affiliation (eg, Buddhism, Orthodox), 10.6% declared being atheist or agnostic, and 8.6% of participants chose “none of the above” answer.

Moral disapproval of pornography use was measured with one item (“I believe that pornography use is morally wrong”), following other research on moral incongruence as a predictor of pornography addiction (eg, Grubbs et al25). The response scale was from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Moral incongruence–related distress was assessed with one item: “Often I felt strong discomfort because of the fact that my sexual fantasies, thoughts and behaviors were inconsistent with my moral and/or religious beliefs.” The participants answered on a scale: 2—“This statement was true for my life for at least 6 out of last 12 months,” 1—“This statement was true for my life, but not during the last 12 months”, and 0—“This statement was never true for me.”

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the PPMI model and test our predictions, we conducted path analysis, with the use of IBM SPSS Amos51 using maximum likelihood estimation. Following the standards adopted in the literature, goodness of fit was assessed using the following criteria: a comparative fit index (CFI) value greater than 0.95, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) lower than 0.06, and a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) lower than 0.08.52

Preregistration and Other Analyses Based on the Same Data Set

Sample characteristics, measures used, research questions, and a fundamental, 3-path design of the model were preregistered via the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/qcwxa). However, the core of the preregistration report is dedicated to other investigations, which were preregistered with a higher degree of detail. These analyses, based on the same data set but answering different, however related, research questions, are reported elsewhere.27

Ethics

The methods and materials for this study were approved by the ethics committee at Institute of Psychology, Polish Academy of Sciences. Before completing the study, all participants completed an informed consent form.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

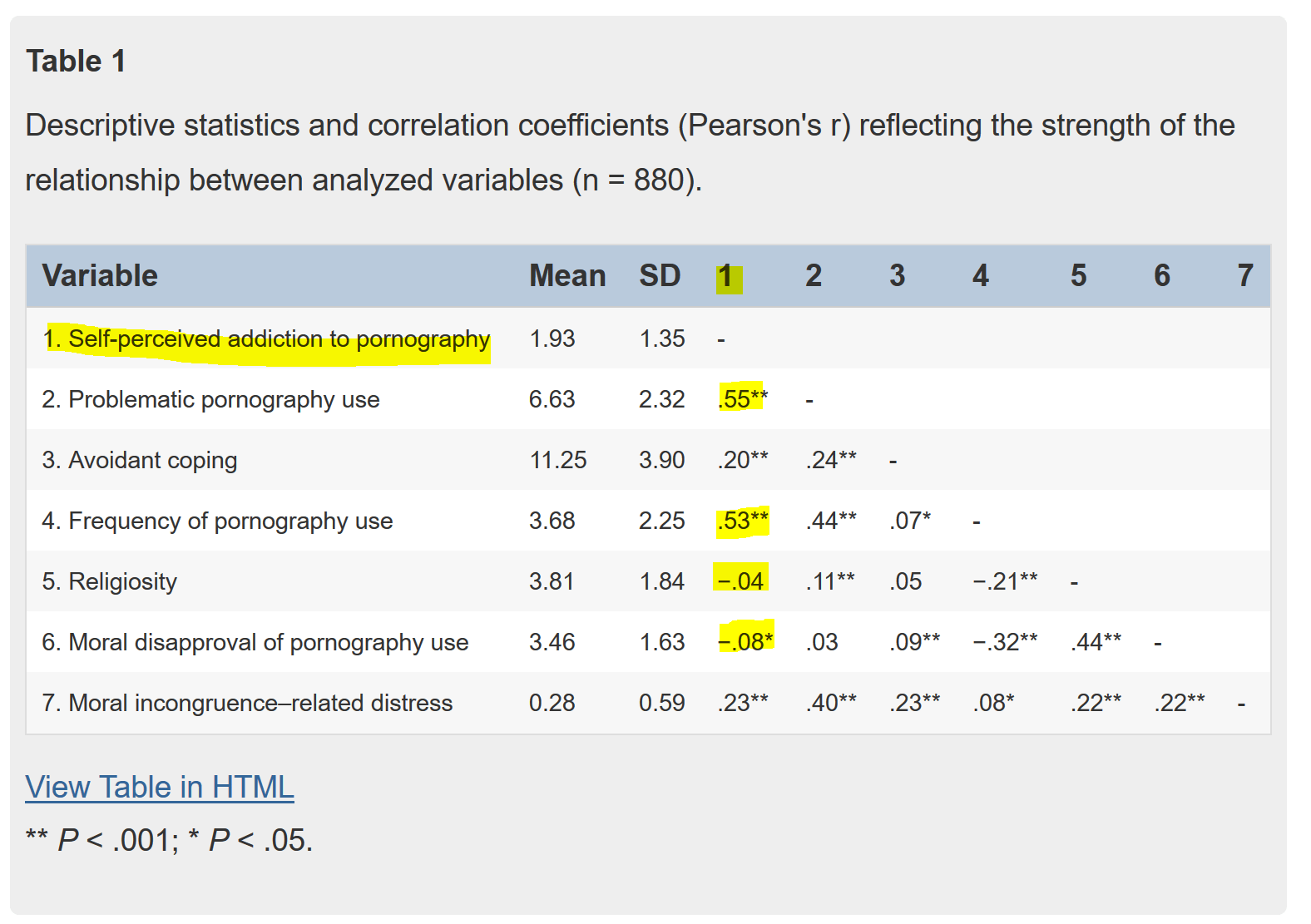

Table 1 contains descriptive statistics and correlations between all analyzed variables. Overall, 20.5% of participants who used pornography in their lifetime (n = 880) to some degree agreed that pornography use is morally wrong (answer options ranged from somewhat agree to strongly agree), although only 5.8% agreed with this statement strongly (strongly agree answer). Problematic pornography use symptoms were to a large degree distinct from self-perceived addiction to pornography; correlation between these 2 constructs was r = .55 (Table 1).

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-perceived addiction to pornography | 1.93 | 1.35 | – | ||||||

| 2. Problematic pornography use | 6.63 | 2.32 | .55** | – | |||||

| 3. Avoidant coping | 11.25 | 3.90 | .20** | .24** | – | ||||

| 4. Frequency of pornography use | 3.68 | 2.25 | .53** | .44** | .07* | – | |||

| 5. Religiosity | 3.81 | 1.84 | −.04 | .11** | .05 | −.21** | – | ||

| 6. Moral disapproval of pornography use | 3.46 | 1.63 | −.08* | .03 | .09** | −.32** | .44** | – | |

| 7. Moral incongruence–related distress | 0.28 | 0.59 | .23** | .40** | .23** | .08* | .22** | .22** | – |

** P < .001; * P < .05.

Evaluating the PPMI Model

Model 1—Self-Perceived Addiction

The evaluated model is depicted in Figure 1. Self-perceived addiction to pornography (“I am addicted to pornography”) is placed in the role of main dependent variable in the model. Avoidant coping positively predicted self-perceived addiction (β = 0.13, P < .001), being also positively, although weakly, related to the frequency of pornography use (β = 0.10, P = .001). Frequency of pornography use, in turn, was the strongest predictor of self-perceived addiction (β = 0.52, P < .001) and a positive predictor of moral incongruence related distress (β = 0.17, P < .001). In the moral incongruence path, religiosity was a positive predictor of moral disapproval of pornography use (β = 0.44, P < .001) and positively influenced the distress connected to moral incongruence (β = 0.16, P < .001). Religiosity was a weak negative predictor of frequency of pornography use (β = -0.09, P = .013), but its influence on self-perceived addiction was not significant (β = 0.03, P = .368). In line with our prediction, moral disapproval of pornography was a negative contributor to frequency of pornography use (β = -0.29, P < .001) but positively predicted moral incongruence–related distress (β = 0.19, P < .001). Furthermore, moral incongruence–related distress was a positive, moderately strong predictor of self-perceived addiction (β = 0.15, P < .001) (Figure 1). In addition, experiencing distress related to moral incongruence was positively connected with avoidant coping strategies (r = 0.21, P < .001), which was predicted, although is not depicted, within the figure for the sake of clarity. The model explained 33.9% of variance in self-appraisals of addiction. The fit indices for the model reflected a very good fit: χ2(3) = 9.04, P = .029, CFI = 0.992, RMSEA = 0.048, and SRMR = 0.0274.

Model 2—Hypersexual Behavior

To investigate the applicability of the PPMI model to a broader construct of problematic pornography use, we estimated the same model with the BPS general score as a main dependent variable (Figure 2). Avoidant coping (β = 0.13, P < .001) and frequency of pornography use (β = 0.43, P < .001) predicted problematic pornography use positively, but the relation was stronger for the latter variable. Religiosity significantly predicted problematic pornography use (β = 0.13, P < .001), as did moral incongruence-related distress (β = 0.31, P < .001) (Figure 2). The rest of the relationships did not differ from the first model depicted in Figure 1. The analyzed model explained 35.9% of variance in hypersexual behavior symptoms. The fit indices for our second model also reflected a very good fit: χ(3) = 9.93, P = .019, CFI = 0.991, RMSEA = 0.051, and SRMR = 0.0282.

Figure 2

Path analysis evaluating the Pornography Problems Due to Moral Incongruence model (based on a sample of n = 880), proposed by Grubbs et al.3 Problematic pornography use, as operationalized by the Brief Pornography Screener is placed in the role of main dependent variable. Standardized path coefficients are shown on the arrows (**P < .001, *P < .05). The dotted line indicates a nonsignificant relationship. For the sake of readability of the figure, the model does not depict the correlation between moral incongruence–related distress and avoidant coping (r = 0.21**).

Discussion

The presented work is one of only a few attempting a nonfragmentary assessment of the validity of any model of pornography addiction, problematic pornography use or problematic sexual behavior, and the first to do so for the PPMI model. On a general level, our results confirmed the appropriateness of the basic shape of the model to depict the structure of predictors of both self-perceived addiction to pornography (model 1, Figure 1) and problematic pornography use (model 2, Figure 2). However in some places, our results diverge from the predictions stemming from the model, and there are at least several specific but important issues that require consideration as well as have potential implications for the shape of the model and future research.

As described previously, the analysis reported in the present study was based on 3 paths proposed within the PPMI model: dysregulation path (as indicated by avoidant coping), habits of use path (indicated by frequency of pornography use) and moral incongruence path (operationalized by religiosity, moral disapproval of pornography use, and moral incongruence–related distress). Overall, the results showed that all 3 paths uniquely and significantly contribute to explaining both self-perceived addiction and a broader set of symptoms that fall under the label of problematic pornography use. Moreover, our results confirmed that problematic pornography use symptoms are distinct from simple declarations of being an addict. The correlation between these 2 constructs was r = 0.55. Based on our results, none of the 3 paths postulated within the model can be reduced to the other or eliminated without deterioration in the quality and predictive value of the model. This confirms the basic prediction stemming from the PPMI model.3 Estimated models explained a significant portion of variance in self-perceived addiction (33.9%, model 1) and problematic pornography use (35.9%, model 2).

Conclusions regarding each of the 3 paths of the model are delineated in the following section.

Moral Incongruence Path

People experiencing moral incongruence–related distress reported higher levels of self-perceived addiction and problematic pornography use. This confirms the prediction of the authors of the PPMI model3,31 regarding the role that moral incongruence plays in shaping the self-appraisals of self-perceived addiction24 and extends it to more general problematic pornography use symptoms. However, the prediction of the model is that moral incongruence should be the stronger predictor of self-perceived addiction to pornography than frequency of use and dysregulation,3,31 which is not confirmed by our findings. Our results are more in line with recent work showing that frequency of pornography use is a stronger predictor of self-perceived addiction to pornography than moral incongruence26 (refer also to the study by Lewczuk et al27 for an analysis conducted on the same sample as the present study). It is also possible that the lower impact of moral incongruence–related distress on self-perceived addiction is at least partially caused by a slightly lower level of moral disapproval of pornography use in the current Polish sample, compared with, for example, a representative sample of U.S. adults.25 In our study, 20.5% of participants who used pornography in their lifetime agreed that pornography use is morally wrong (answer options ranged from “somewhat agree” to “strongly agree”), while the same answer was given by 24% of Americans. Moreover, based on the same measure, U.S. participants declared to be slightly more religious on average (M = 4.10, SD = 1.9525) than Polish participants in the current sample (M = 3.81, SD = 1.84), which may also explain the weaker impact of the moral incongruence path on self-perceived pornography addiction than the PPMI model based mostly on research performed on the U.S. predicts.

In addition, moral incongruence–related distress was more strongly connected to problematic pornography use than to self-perception of addiction. A possible explanation for this pattern is that, compared with self-perceived addiction, problematic pornography use encompasses a broader group of cognitive and affective consequences and determinants of pornography use. One of them is increased levels of guilt regarding pornography use, which can be a consequence of moral incongruence.20 One of the 5 statements in the BPS,34 which was an indicator of problematic pornography use in our study, reads “You continue to use pornography even though you feel guilty about it.” The relation between self-labeling as an addict and moral incongruence–related distress is theoretically not as close as in other studies, which is reflected by our findings.

Next, our results generally confirmed the specifics of the chain of influence between morality-related variables, although not without a caveat. More religious people were more inclined to see pornography use as morally reprehensible and were more prone to experiencing feelings of incongruence between own sexual behavior and adopted beliefs, attitudes, and norms. The impact of religion was not strong in these cases, as our method of measuring it does not directly invoke a religious context (see the Introduction section for more information on this issue). As expected, distress connected to behavior-attitudes misalignment was determined by 2 additional factors: frequency of the behavior (frequency of pornography use) and restrictiveness of the attitudes (moral disapproval of pornography; refer to the study by Grubbs et al3). However, although religiosity and moral disapproval significantly predicted moral incongruence–related distress, their contribution was somewhat limited. Other possible predictors should be investigated, both connected to other sources of norms that can determine disapproval of pornography, for example, sociopolitical views, religious fundamentalism53,54 or certain branches of feminism,55 as well as variables related to the awareness and sensitivity to own behaviors being incongruent with own beliefs, attitudes, and internalized norms (eg, self, awareness, concern over mistakes, perfectionism, the centrality of the norms that motivate attitudes toward pornography and sexuality). Here, we echo the suggestions that were voiced by other authors in their commentaries for the model.19,22

In addition, our results showed that, controlling for other variables, more religious people declared higher levels of problematic pornography use. The influence of religiosity on problematic pornography use was weak, but present—which is in agreement with at least a significant portion of previous studies showing a weak, positive relationship between religiosity and problematic pornography use symptoms25,26 (refer also to the study by Lewczuk et al27). A corresponding relation was not found for self-perceptions of addiction.

Habits of Use Path

Frequency of pornography use was the strongest predictor of self-perceived addiction in model 1 and of problematic pornography use in model 2. This indicates that the self-appraisal of pornography-related problems does not merely rely on perceiving this behavior as transgressing one’s personal norms, that is, it is not a function of mere convictions (refer to the discussion in the study by Humphreys56). A significant portion of the variance is better explained by the frequency of use, which validates the disorder model of problematic pornography use and is similar to the symptomology of at least some cases of substance use disorders and other behavioral addictions, for which excessive use during at least some part of the course of the disorder is a definitional criterion (refer to the study by Kraus et al1 and Potenza et al57). Frequency of pornography use was also a significant predictor of problematic pornography use, although its influence was slightly weaker than for self-perception of addiction (β = 0.43 vs β = 0.52). This is understandable, given that problematic use has a broader scope than self-perception of addiction, encompassing not only excessive pornography use but also loss of control, using pornography as a coping mechanism and guilt connected to pornography use.34

Dysregulation Path

Avoidant coping style was an indicator of dysregulation in our model. People using an avoidant coping style more frequently were also more inclined to see themselves as pornography addicts and had a higher severity of symptoms of problematic pornography use. This is in line with previous research, which showed the specific importance of an avoidant coping style for problematic sexual behavior.39, 40, 41 This result is also in agreement with studies showing that engagement in sexual behaviors itself can constitute an avoidance strategy (eg, avoiding negative emotions associated with other areas of one’s life). However, the impact on avoidant coping for both dependent variables was weak (β = 0.15, P < .001) and was not stronger for problematic pornography use than for self-appraisals of addiction. This can be considered surprising, as problematic pornography use has a pornography-as-coping component (“You find yourself using pornography to cope with strong emotions, eg, sadness, anger, loneliness, etc.” is one of BPS items that operationalized problematic pornography use in our study).

Implications for the Shape of the Model and Future Research

Our findings indicate that the PPMI model can serve as a general model of factors contributing to self-perception of pornography addiction and problematic pornography use. However, the dysregulation path is underdeveloped in the current version of the model. This has also been pointed out by other researchers.16 This path should be delineated with more detail and extended. In their initial proposition of the model, Grubbs et al3 focused on moral incongruence–related factors describing the dysregulation path with less detail. This approach is understandable as moral incongruence is a central focus of the model. However, as a consequence, the current conceptualization of the PPMI model places all dysregulation-related factors (such as emotion dysregulation, impulsivity, coping, compulsivity) into one general and unspecified category and abstains from depicting mechanisms of influence between these variables, ascribing them differential degrees of importance or depicting relations between dysregulation-related variables and moral incongruence–related variables. Such relations have been proposed by others16,22 and are also visible in our analysis, as avoidant coping was connected to moral incongruence–related distress (r = 0.21, P < .001) possibly indicating that avoidant coping strategies can serve as a way of dealing with moral incongruence.

As the PPMI model was initially validated in the present study, we postulate that it should be extended and possibly reshaped into an even more ambitious, general model in which dysregulation-related variables will be treated with the same degree of carefulness as morality-related ones. To achieve this, specific models—such as the current version of the PPMI model—should be merged with broader models (eg, I-PACE model12,58) that go into more detail regarding behavior dysregulation–related factors, but, as of now, neglect the role of morality-related variables. It seems that only this approach would allow for the full picture of factors influencing both lay self-perceptions of addiction and problematic pornography use to be accounted for. These 2 branches of research should not and cannot develop separately because of their possible mutual influence.16,22 Because of this interdependence, the shape of the moral incongruence path cannot be definitively established when the dysregulation-related side of the model is underdeveloped.

In future studies, other indicators of general dysregulation (eg, impulsivity, maladaptive emotion regulation, perfectionism) should be tested within the PPMI model to extend and provide further support for the discussed framework. Such an extension seems to have been predicted and welcomed by the authors of the model,31 which we fully agree with.

Another issue worth pointing out is that our analysis is based on a populational sample. One of the important future directions for further research is to also verify the model based on clinical samples, experiencing a clinical level of symptoms of problematic pornography. This is crucially important because the significance of factors predicting problematic pornography use can change the clinical level, compared with populational investigations. Future studies should also apply the PPMI model to CSBD recognized in the ICD-1113,14 when screening measures for this disorder become available for use. We agree with other researchers who suggested studying behavior-norms misalignment for sexual behaviors other than problematic pornography use,20 which may lead to an extension of the model to explain general problematic sexual behavior symptoms.

Additional concerns about the issue of operationalizing moral incongruence vs moral disapproval of pornography use (see Material and Methods section) and self-perceived addiction vs disordered pornography use based on formal clinical definitions (such as problematic pornography use, see the Introduction section) were noted in the earlier parts of the manuscript.

The current research extends research on the PPMI model to another cultural context, namely, Polish participants. However, Poland shares cultural similarities with the United States as it is a predominantly Christian country (77.3% of participants in the current analysis declared being Catholic). Future research should further validate the model, based on different religious and cultural circles.

Limitations

Some of the limitations of the present study were already noted (single dysregulation-related factor). We also note that the present work is based on cross-sectional research design, which precludes analyses of directionality or causality. That is, although the present work is consistent with the PPMI, without longitudinal observations that examine trajectories of these variables over time, it is impossible to conclusively evaluate any model of problematic pornography use. Finally, we did not include a definition of pornography for the participants in the online survey.

Conclusions

Overall, our results indicate that the PPMI model is, in its current nascent stage, already a promising framework to describe factors influencing both self-perception of pornography addiction and problematic pornography use. Boiling predictors of both of these phenomena down to 3 groups of influencing factors, dysregulation, habits of use, and moral incongruence, is an obvious heuristic, although—in light of our results—a useful and fairly adequate one. The described 3-group conceptual approach is promising and parsimonious enough that we recommend its further investigation in future research endeavors. As factors related to dysregulation, habits of use, and moral incongruence all uniquely contribute to the severity of symptoms in both self-perception of addiction and problematic pornography use, all of them should be taken into account in treatment. Although negative symptoms stemming from each of the 3 paths can look similar, they have a significantly different etiology, which should merit a differential treatment approach, and possibly differential diagnosis (refer to the study by Grubbs et al,3,31 Kraus and Sweeney;18 also refer incongruence-related distress as an exclusion criterion for CSBD: World Health Organisation,13 Kraus et al,14 and Gola et al59). Future research should determine treatment approaches effective for addressing factors linked to dysregulation, habits of use, and moral incongruence. We see these considerations as central rather than peripheral, now that CSBD has been included in the ICD-1113 and key to avoid the overpathologization of high-frequency sexual behavior60, 61, 62 in individuals who do not experience diminished control or in individuals for whom moral or social norms provoke negative views of one’s own sexual activity, causing them to over-control sexual activities as a result.18,63 Diagnosing CSBD for those individuals would constitute a misdiagnosis. The diagnostic criteria for CSBD are abundantly clear that distress secondary to religious beliefs or moral disapproval of sexual behavior is not alone sufficient for diagnosing this disorder.14 However, given that such moral distress may change individual self-perceptions of their sexual behaviors, there is a need for care in applying this diagnosis. Clinicians must pay close attention to these distinctions in the process of diagnosis to avoid CSBD being an “umbrella disorder” mistakenly used for labeling problematic psychological states with differing etiologies. In addition, as moral incongruence can possibly be a factor influencing self-perceptions of other behavioral addictions (internet addiction, social networking addiction, gaming addiction),27 this concern is not specific only to self-reported pornography addiction.

Finally, our results support the notion that simple declarations of being an addict are, to a large degree, distinct from the severity of problematic pornography use symptoms, even when both of these constructs are based on declarative measurement. Both self-perceived addiction and problematic pornography use should be investigated with regard to the PPMI model and related research questions.

Statement of authorship

- Category 1

- (a)

Conception and Design

-

Karol Lewczuk; Mateusz Gola

-

- (b)

Acquisition of Data

-

Karol Lewczuk; Iwona Nowakowska

-

- (c)

Analysis and Interpretation of Data Karol Lewczuk; Iwona Nowakowska

- Category 2

- (a)

Drafting the Article

-

Karol Lewczuk; Agnieszka Glica

-

- (b)

Revising It for Intellectual Content

-

Mateusz Gola; Joshua B. Grubbs

-

- Category 3

- (a)

Final Approval of the Completed Article

-

Karol Lewczuk; Mateusz Gola; Joshua B. Grubbs; Agnieszka Glica; Iwona Nowakowska

-

References

- Kraus, S.W., Voon, V., and Potenza, M.N. Should compulsive sexual behavior be considered an addiction?. Addiction. 2016; 111: 2097–2106

|

- Bancroft, J. and Vukadinovic, Z. Sexual addiction, sexual compulsivity, sexual impulsivity, or what? Toward a theoretical model. J Sex Res. 2004; 41: 225–234

|

- Grubbs, J.B., Perry, S.L., Wilt, J.A. et al. Pornography problems due to moral incongruence: An integrative model with a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Sex Behav. 2019; 48: 397–415

|

- Stein, D.J. Classifying hypersexual disorders: Compulsive, impulsive, and addictive models. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008; 31: 587–591

|

- Walton, M.T., Cantor, J.M., Bhullar, N. et al. Hypersexuality: A critical review and introduction to the “sexhavior cycle”. Arch Sex Behav. 2017; 46: 2231–2251

|

- Wéry, A. and Billieux, J. Problematic cybersex: Conceptualization, assessment, and treatment. Addict Behav. 2017; 64: 238–246

|

- de Alarcón, R., de la Iglesia, J.I., Casado, N.M. et al. Online porn addiction: What we know and what we don’t – A systematic review. J Clin Med. 2019; 8: 91

|

- Gold, S.N. and Heffner, C.L. Sexual addiction: Many conceptions, minimal data. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998; 18: 367–381

|

- Gola, M. and Potenza, M.N. The proof of the pudding is in the tasting: Data are needed to test models and hypotheses related to compulsive sexual behaviors. Arch Sex Behav. 2018; 47: 1323–1325

|

- Gola, M. and Potenza, M.N. Promoting educational, classification, treatment, and policy initiatives: Commentary on: Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder in the ICD-11 (Kraus et al, 2018). J Behav Addict. 2018; 7: 208–210

|

- Prause, N. Evaluate models of high-frequency sexual behaviors already. Arch Sex Behav. 2017; 46: 2269–2274

|

- Brand, M., Young, K.S., Laier, C. et al. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016; 71: 252–266

|

- World Health Organization. ICD-11 – Compulsive sexual behavior disorder. (Available at:)

|

- Kraus, S.W., Krueger, R.B., Briken, P. et al. Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder in the ICD-11. World Psychiatry. 2018; 17: 109–110

|

- Fuss, J., Lemay, K., Stein, D.J. et al. Public stakeholders’ comments on ICD-11 chapters related to mental and sexual health. World Psychiatry. 2019; 18: 233–235

|

- Brand, M., Antons, S., Wegmann, E. et al. Theoretical assumptions on pornography problems due to moral incongruence and mechanisms of addictive or compulsive use of pornography: Are the two “conditions” as theoretically distinct as suggested?. Arch Sex Behav. 2019; 48: 417–423

|

- Fisher, W.A., Montgomery-Graham, S., and Kohut, T. Pornography problems due to moral incongruence. Arch Sex Behav. 2019; 48: 425–429

|

- Kraus, S.W. and Sweeney, P.J. Hitting the target: Considerations for differential diagnosis when treating individuals for problematic use of pornography. Arch Sex Behav. 2019; 48: 431–435

|

- Vaillancourt-Morel, M.P. and Bergeron, S. Self-perceived problematic pornography use: Beyond individual differences and religiosity. Arch Sex Behav. 2019; 48: 437–441

|

- Walton, M.T. Incongruence as a variable feature of problematic sexual behaviors in an online sample of self-reported “sex addiction”. Arch Sex Behav. 2019; 48: 443–447

|

- Willoughby, B.J. Stuck in the porn box. Arch Sex Behav. 2019; 48: 449–453

|

- Wright, P.J. Dysregulated pornography use and the possibility of a unipathway approach. Arch Sex Behav. 2019; 48: 455–460

|

- Festinger, L. Cognitive dissonance. Sci Am. 1962; 207: 93–106

|

- Grubbs, J.B. and Perry, S.L. Moral incongruence and pornography use: A critical review and integration. J Sex Res. 2019; 56: 29–37

|

- Grubbs, J.B., Kraus, S.W., and Perry, S.L. Self-reported addiction to pornography in a nationally representative sample: The roles of use habits, religiousness, and moral incongruence. J Behav Addict. 2019; 8: 88–93

|

- Grubbs, J.B., Grant, J.T., and Engelman, J. Self-identification as a pornography addict: Examining the roles of pornography use, religiousness, and moral incongruence. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2018; 25: 269–292

|

- Lewczuk K, Nowakowska I, Lewandowska K, et al. Moral incongruence and religiosity as predictors of self-perceived behavioral addictions (pornography, internet, social media and gaming addiction). Preregistered study based on a nationally representative sample. Under review.

- Grubbs, J.B., Exline, J.J., Pargament, K.I. et al. Internet pornography use, perceived addiction, and religious/spiritual struggles. Arch Sex Behav. 2017; 46: 1733–1745

|

- Gola, M., Lewczuk, K., and Skorko, M. What matters: quantity or quality of pornography use? Psychological and behavioral factors of seeking treatment for problematic pornography use. J Sex Med. 2016; 13: 815–824

|

- Lewczuk, K., Szmyd, J., Skorko, M. et al. Treatment seeking for problematic pornography use among women. J Behav Addict. 2017; 6: 445–456

|

- Grubbs, J.B., Perry, S., Wilt, J.A. et al. Response to Commentaries. Arch Sex Behav. 2019; 48: 461–468

|

- Corrigan, P.W., Bink, A.B., Schmidt, A. et al. What is the impact of self-stigma? Loss of self-respect and the “why try” effect. J Ment Health. 2015; 5: 10–15

|

- Fernandez, D.P., Tee, E.Y., and Fernandez, E.F. Do Cyber Pornography Use Inventory-9 scores reflect actual compulsivity in internet pornography use? Exploring the role of abstinence effort. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2017; 24: 156–179

|

- Kraus S, Gola M, Grubbs JB, et al., Validation of a Brief Pornography Screener Across Multiple Samples. Under Review.

- Fernandez, D.P. and Griffiths, M.D. Psychometric instruments for problematic pornography use: A systematic review. (0163278719861688)Eval Health Prof. 2019;

|

- Grubbs, J.B., Exline, J.J., Pargament, K.I. et al. Transgression as addiction: Religiosity and moral disapproval as predictors of perceived addiction to pornography. Arch Sex Behav. 2015; 44: 125–136

|

- Grubbs JB, Kraus SW, Perry SL, et al. Moral Incongruence and Compulsive Sexual Behavior: Results from Cross-Sectional Interactions and Parallel Growth Curve Analyses. Under Review.

- Grubbs, J.B., Wilt, J.A., Exline, J.J. et al. Moral disapproval and perceived addiction to internet pornography: A longitudinal examination. Addiction. 2017; 13: 496–506

|

- Lew-Starowicz M, Lewczuk K, Nowakowska I, et al. Compulsive sexual behavior and dysregulation of emotion. Sex Med Rev. In press.

- Reid, R.C., Harper, J.M., and Anderson, E.H. Coping strategies used by hypersexual patients to defend against the painful effects of shame. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2009; 16: 125–138

|

- Levin, M.E., Lee, E.B., and Twohig, M.P. The role of experiential avoidance in problematic pornography viewing. Psychol Rec. 2019; 69: 1–12

|

- Herman-Stabl, M.A., Stemmler, M., and Petersen, A.C. Approach and avoidant coping: Implications for adolescent mental health. J Youth Adolesc. 1995; 24: 649–665

|

- Holahan, C.J., Moos, R.H., Holahan, C.K. et al. Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: A 10-year model. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005; 73: 658–666

|

- Roth, S. and Cohen, L.J. Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. Am Psychol. 1986; 41: 813–819

|

- Kohut, T. and Štulhofer, A. The role of religiosity in adolescents’ compulsive pornography use: A longitudinal assessment. J Sex Marital Ther. 2018; 44: 759–775

|

- Martyniuk, U., Briken, P., Sehner, S. et al. Pornography use and sexual behavior among Polish and German university students. J Sex Marital Ther. 2016; 42: 494–514

|

- Grubbs, J.B., Sessoms, J., Wheeler, D.M. et al. The Cyber-Pornography Use Inventory: The development of a new assessment instrument. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2010; 17: 106–126

|

- Reid, R.C., Garos, S., and Carpenter, B.N. Reliability, validity, and psychometric development of the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory in an outpatient sample of men. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2011; 18: 30–51

|

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief cope. Int J Behav Med. 1997; 4: 92

|

- Schnider, K.R., Elhai, J.D., and Gray, M.J. Coping style use predicts posttraumatic stress and complicated grief symptom severity among college students reporting a traumatic loss. J Couns Psychol. 2007; 54: 344

|

- Arbuckle, J.L. IBM SPSS Amos 23 user’s guide. (Available at:) (Accessed August 18, 2019)Amos Development Corporation, ; 2014

|

- Hu, L.T. and Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999; 6: 1–55

|

- Droubay, B.A., Butters, R.P., and Shafer, K. The pornography debate: Religiosity and support for censorship. J Relig Health. 2018; : 1–16

|

- Lambe, J.L. Who wants to censor pornography and hate speech?. Mass Commun Soc. 2004; 7: 279–299

|

- Ciclitira, K. Pornography, women and feminism: Between pleasure and politics. Sexualities. 2004; 7: 281–301

|

- Humphreys, K. Of moral judgments and sexual addictions. Addiction. 2018; 113: 387–388

|

- Potenza, M.N., Gola, M., Voon, V. et al. Is excessive sexual behaviour an addictive disorder?. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017; 4: 663–664

|

- Brand, M., Wegmann, E., Stark, R. et al. The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond Internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019; 104: 1–10

|

- Gola M, Lewczuk K, Potenza, MN, et al. Missing elements in criteria for compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. Under Review.

- Klein, M. Sex addiction: A dangerous clinical concept. SIECUS Rep. 2003; 31: 8–11

|

- Winters, J. Hypersexual disorder: A more cautious approach [Letter to the Editor]. Arch Sex Behav. 2010; 39: 594–596

|

- Ley, D., Prause, N., and Finn, P. The emperor has no clothes: A review of the ‘pornography addiction’ model. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2014; 6: 94–105

|

- Efrati, Y. God, I can’t stop thinking about sex! The rebound effect in unsuccessful suppression of sexual thoughts among religious adolescents. J Sex Res. 2019; 56: 146–155

|