COMMENTS: A narrative review (full paper here). The two main tables summarizing this review:

March–April, 2020 Volume 34, Issue 2, Pages 191–199

Gail Hornor, DNP, CPNP, SANE-P,Correspondence information about the author DNP, CPNP, SANE-P Gail Hornor Email the author DNP, CPNP, SANE-P Gail Hornor

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2019.10.001

Introduction

Children and adolescents are growing up in a digital world. The rapid expansion of the development, accessibility, and use of cellular phones and the Internet is changing human existence. Adolescents are absorbed in the use of technology; however, this behavior is also becoming characteristic of younger children as well (Livingstone & Smith, 2014). Consider that in 1970, the average American child began to watch television regularly at age 4, yet today, children begin interacting with digital media at the age of 4 months (Reid Chassiakos et al., 2016). Although technology can enhance communication, recreation, and education, its use can also present risks to children and adolescents. One such risk is exposure to pornography. It is difficult to dispute the fact that the Internet has revolutionized the pornography industry and has substantially expanded child and adolescent access to pornography. The Internet allows instant access to a wide variety of pornography that can be viewed anywhere, even from the privacy of a child’s room, with little to no parental knowledge (Wright & Donnerstein, 2014). This continuing educational article will explore child and adolescent Internet pornography exposure in terms of definition, epidemiology, predictors, consequences, and implications for practice.

DEFINITION

Pornography can be broadly defined as professionally produced or consumer-generated pictures or videos intended to sexually arouse the consumer (Peter & Valkenburg, 2016). Traditional pornography relies on traditional media venues such as television, movies, and magazines. Internet pornography viewing is the online viewing or downloading of pictures and videos where genitals are exposed, and/or people are having sex with the intention of stimulating a sexual reaction in the viewer (Peter & Valkenburg, 2016). A variety of sexual activities are depicted in both genres of pornography, including but not limited to masturbation, oral sex, and vaginal and anal intercourse, all with a focus on the genitals.

The Internet has transformed pornography consumption. Online pornography differs from traditional pornography in several ways. The Internet has changed the fundamental relationship between the individual and pornography, allowing access to an endless supply of free and diverse material (Wood, 2011). Online pornography is accessible from virtually anywhere with an Internet connection and is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The Internet allows for the global dissemination of pornography via the Triple-A Engine: accessibility, affordability, and anonymity (Cooper, 1998). Traditional pornography requires acquiring a magazine or film from a store or a friend or viewing a television program, all of which carry a perception of increased risk of parental detection. Online pornography exposure is much more difficult for parents to monitor than traditional media exposure (Collins et al., 2017). The child or teen often perceives viewing online pornography as private and anonymous, which emboldens them to search for material that they would not search for via traditional media.

The content of traditional pornography is somewhat regulated, whereas the content of online pornography is widely unregulated (Wright & Donnerstein, 2014). Studies suggest that Internet pornography often portrays extreme forms of sexuality and sexually violent content more so than traditional pornography (Collins et al., 2017; Strasburger, Jordan, & Donnerstein, 2012). Studies also indicate that Internet pornography presents sexual scripts supportive of aggressive and gender-stereotypic behavior (Bridges, Wosnitzer, Scharrer, Sun & Liberman, 2010). Men are perpetrators and women are victims typically. A variety of aggressive behaviors accompanying sex are often portrayed, including choking, spanking, kicking, use of weapons, whipping, smothering, and biting (Wright & Donnerstein, 2014). Derogatory namecalling is often present. Depictions of rape can be found via an Internet search to fuel fantasies or enhance rape-supportive scripts (Gossett & Byrne, 2002). Online pornography provides motivational, disinhibiting, and opportunity aspects that make it different from traditional pornography in terms of potential effects on children and adolescents (Malamuth, Linz, & Yao, 2005). It can be engaging and interactive, yielding a potential for increased viewing time and learning. Online chat rooms and blogs provide support and reinforcement for these pornographic images and messages.

Child and adolescent pornography exposure can be either intentional or unintentional. Examples of unintentional exposure include the opening of unsolicited messages or receiving spam emails (Chen, Leung, Chen, & Yang, 2013), mistyping Web site addresses, searching for terms that have a nonsexual as well as sexual meaning (Flood, 2007), or accidentally viewing pop-up images and advertisements (evčíková, Šerek, Barbovschi, & Daneback, 201). Intentional pornography exposure is deliberate and purposeful, often involving an active online search for the material. It is unclear to what extent unintentional online pornography viewing contributes to intentional pornography viewing.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

It is impossible to determine the exact number of children and adolescents unintentionally and intentionally exposed to pornography. The prevalence rate varies per study. The prevalence rates for unintentional adolescent pornography exposure range from 19% (Mitchell & Wells, 2007) to 32% (Hardy, Steelman, Coyne, & Ridge, 2013). A nationally representative study of U.S. youth between the ages of 10 and 17 years indicated that 34% of the study population intentionally viewed pornography (Wolak, Mitchell, & Finkelhor, 2007). However, younger children in that study, aged 10 to 11 years were unlikely to seek pornography, with only 2% to 5% of boys and 1% of girls reporting intentional pornography viewing (Wolak et al., 2007). Ybarra, Mitchell, Hamburger, Diener-West, & Leaf (2011)) found 15% of youth aged 12 to 17 years reported intentional pornography exposure in the past year. A U.S. study of nearly 1,000 adolescents reported that 66% of males and 39% of females had viewed online pornography (Short, Black, Smith, Wetterneck, & Wells, 2012). Pornography exposure in children less than 10 years of age is relatively unexplored (Rothman, Paruk, Espensen, Temple, & Adams, 2017).

However, both unintentional and intentional pornography viewing by children and adolescents increases with age and varies by gender (Mitchell & Wells, 2007; Tsaliki, 2011). Another study of online pornography use in the United States revealed that 42% of 10 to 17 year olds had seen pornography online, with 27% describing the use as intentional (Wright & Donnerstein, 2014). Multiple studies report boys to be more likely to intentionally view pornography than girls (Bleakley, Hennessy, & Fishbein, 2011; Luder et al., 2011). Another study in the United States reported that 54% of boys and 17% of girls between the ages of 15 to 17 years reported intentional online pornography viewing. However, a study of adolescent pornography use in the European Union found variability of gender-based pornography use differed by the social progressiveness of the country (evčíková et al., 201). The gender differences in pornography use were less distinct in more socially liberal countries when compared with more socially conservative ones.

It is important to understand the trajectory of adolescent pornography use. Doornwaard, van den Eijnden, Baams, Vanwesenbeeck, & ter Bogt (2016)) describe three trajectories of pornography use for boys: nonuse or infrequent use, strongly increased use, occasional use, and decreasing use. Pornography use for girls followed three trajectories: stable nonuse or infrequent use, strongly increasing use, and stable occasional use. Although prevalence rates vary among studies, national and international studies reveal that online pornography use is common among boys and not uncommon among girls (Collins et al., 2017).

PREDICTORS OF CHILD AND ADOLESCENT PORNOGRAPHY USE

Certain factors are important predictors of child and adolescent pornography use (Box 1). Demographic factors associated with increased pornography exposure include male gender and lower socioeconomic status (Hardy et al., 2013). Bisexual or gay adolescent males tend to use Internet pornography more often than straight males (Luder et al., 2011). Family factors can also increase risk for pornography exposure. Living in a single-parent home, lower level of caregiver surveillance, and weak emotional bonds with caregivers can lead to increased pornography exposure (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2005).

BOX 1

Predictors of child and adolescent online pornography use

Personality characteristics are also predictive. Children and adolescents who are sensation seekers, engage in delinquent and rule-breaking behavior, and have low self-control are more likely to view pornography (Wright & Donnerstein, 2014). Impulsive, thrill-seeking adolescents tend to engage in higher levels of pornography use (Beyens, Vandenbosch, & Eggermont, 2015; Peter & Valkenburg, 2016; evčíková et al., 201). Adolescents who express dissatisfaction with their lives are also more likely to view pornography (Peter & Valkenburg, 2016). Social deviance also affects pornography use with adolescents who tend to reject other norms and rules being more likely to engage in pornography viewing (Hasking, Scheier, & Abdallah, 2011).

Exposure to psychosocial trauma is also predictive of pornography viewing. Youth who have experienced physical or sexual abuse or who have had a recent negative life experience, such as parental divorce, are more likely to view pornography. Adolescents who experience traditional and/or cyberbullying are also more likely to use Internet pornography (Shek & Ma, 2014). Opportunity for pornography viewing also predicts actual viewing. Youth with Internet access on their phones or a computer in their bedroom are more likely to view pornography. In addition, pornography use is more prevalent among youth who are less religiously involved and who perceive less potential for condemnation upon discovery of their pornography viewing. In summary Peter & Valkenburg (2016)) describe the typical adolescent pornography user as male, at a higher stage of puberty, and a sensation-seeker with weak or troubled family relations.

Some factors appear to be protective against child and adolescent use of pornography. Religiousness, religious internalization and involvement, serve as a protective factor against child and adolescent pornography viewing (Hardy et al., 2013). Religiousness protects against pornography viewing for several reasons. Religiousness contributes to a more conservative attitude toward viewing pornography, increased self-regulation, and social control against the use of pornography. Other factors protective against child and adolescent use of pornography include higher parent education, higher socioeconomic status, greater attachment to school, and healthier family relationships (Brown & L’Engle, 2009; Mesch, 2009).

CONSEQUENCES

Concerns regarding child and adolescent use of pornography center around 3 basic themes: easy access to pornography, the content of the pornography, and the ability of a child or an adolescent to separate pornography fiction from sexuality and sexual relationship facts (Wright & Štulhofer, 2019). When considering possible effects of pornography exposure on the sexual beliefs and behaviors of children and adolescents, it is crucial to consider developmental factors. Children less than 7 or 8 years of age have difficulty differentiating between what is happening on screen and what is happening in real life (Collins et al., 2017). To better understand how and what children learn about sexuality from pornography, it is crucial to consider the cognitive processing ability of the individual. Physical, socioemotional, and cognitive developmental states can affect the importance and processing of pornography viewing (Brown, Halpern, & L’Engle, 2005). The incomplete development of the child and adolescent brain may contribute to engaging in risky behaviors, which may, in turn, affect the extent to which pornography is sought and then, in turn, acted upon (Collins et al., 2017). Child and adolescent brains are immature. Concern exists over their ability to process pornography and to understand the many ways that pornography sex and relationships differ, or should differ, from real-life sex and relationships (Baams et al., 2015). Wright (2011)) proposed a theory to explain the socializing effect of pornography: the sexual script theory. Pornography can provide users with sexual scripts they were previously unaware of (acquisition), reinforce sexual scripts they were already aware of (activation), and by portraying the sexual behaviors as normative, appropriate, and rewarding, encourage the intellectual and behavioral use of sexual scripts (application).

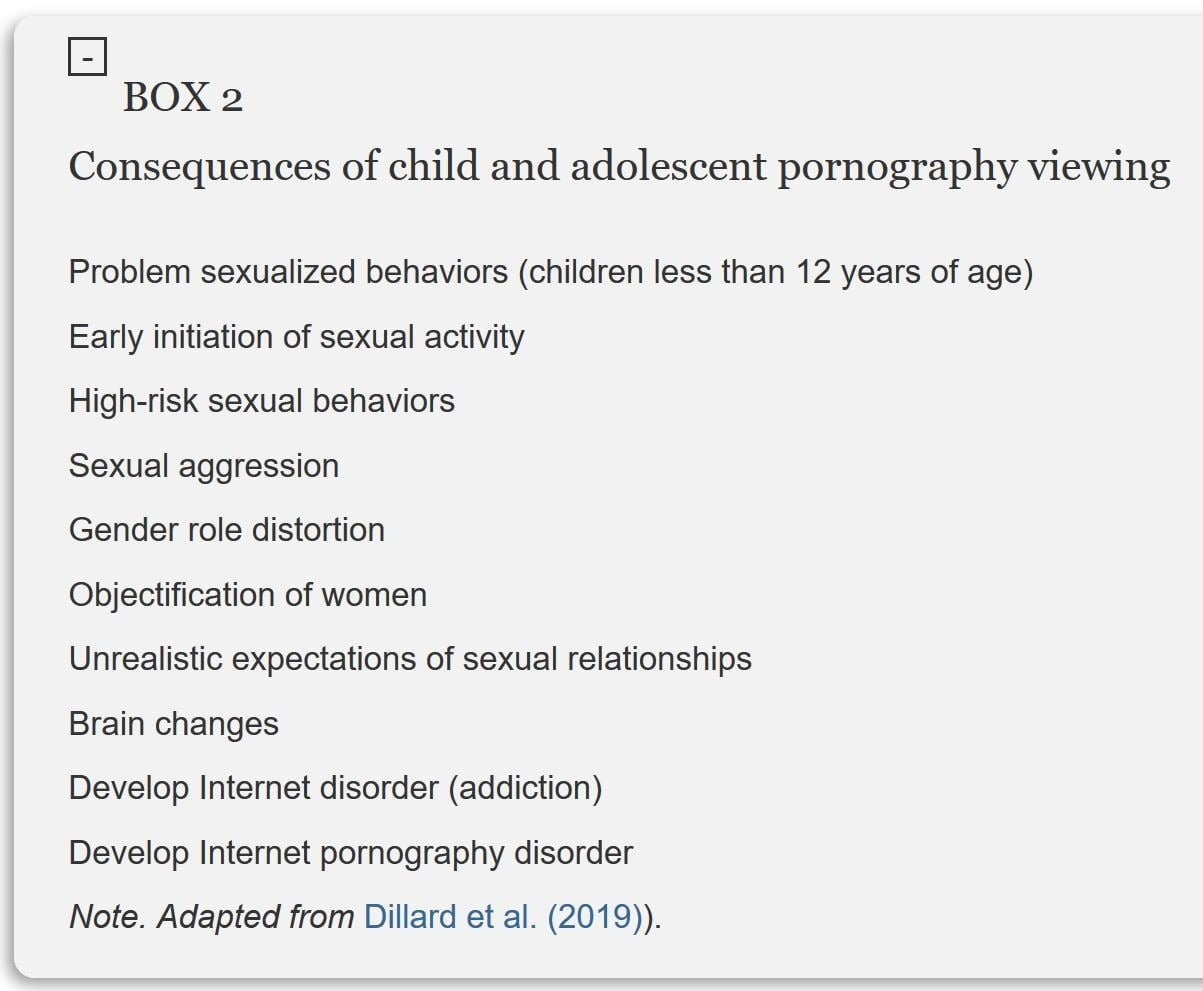

See Box 2 for possible consequences of child and adolescent pornography viewing. The primary concern related to pornography viewing in young children under the age of 12 years is the development of problem sexualized behaviors (PSB). PSB involves sexual knowledge beyond what would be expected for the child’s age and developmental levels, such as children engaging in sophisticated sexual acts such as intercourse or oral sex (Mesman, Harper, Edge, Brandt, & Pemberton, 2019). Chaffin et al. (2008)) states that these PSB in children less than 12 years of age are the result of several factors, including pornography viewing. PSB in young children has also been linked to trauma and violence, insufficient supervision, and impulse control problems (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2009). Dillard, Maguire-Jack, Showalter, Wolf, & Letson (2019)) found children less than 12 years of age who disclosed engaging in pornography viewing were at significantly higher odds of engaging in PSB when compared with their non–pornography exposed peers. Social learning theory provides a framework for understanding this phenomenon. Exposure to pornography at a young age not only introduces children to sexual behaviors but also reinforces the behaviors. Reinforcement occurs because of viewing depictions of rewards (pleasure) when engaging in sexual behaviors (Dillard et al., 2019). Any link between PSB and adolescent sexually abusive behaviors is unclear, and the risk is considered to be low if the child receives proper mental health treatment (Chaffin et al., 2008). However, children engaging in PSB and adolescents engaging in sexually abusive behaviors share common risk factors, including a history of child maltreatment (Yoder, Dilliard, & Leibowitz, 2018) and early exposure to pornography (Dillard et al., 2019).

BOX 2

Consequences of child and adolescent pornography viewing

The easy availability of Internet pornography coupled with an increasing interest in sex in children and adolescents leads to concerns that pornography viewing can become excessive, even addictive (Tsitsika et al., 2009; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2005). Among other potential negative consequences, pornography viewing promotes sexual aggression, risky sexual practices, objectification of women, and hyper-gendered male and female stereotypes (Peter & Valkenburg, 2016). The depictions of sex and relationships in pornography are concerning and promote the concept of impersonal, nonrelational sexual encounters (Peter & Valkenburg, 2016; Wright & Donnerstein, 2014).

Matković, Cohen, & Štulhofer (2018)) examined midadolescent use of pornography and its relationship to adolescent sexual activity. Over 1,000 Croatian adolescents participated in a 3-wave study and were surveyed regarding their use of pornography and their sexual activity 3 times at 1-year intervals. Participants were 16 years of age at baseline. The proportion of sexually active participants increased from 23% at baseline to 38.1% at wave 3 among male adolescents and from a baseline of 19.7% to 38.1% at wave 3 for adolescent females. Adolescent males who reported moderate to high pornography use and female adolescents who reported regular pornography use demonstrated a higher rate of sexual initiation. Viewing sensation-seeking pornography was also associated with sexual initiation in adolescent males.

Internet pornography supports gender-stereotypic behaviors and roles (Wright & Donnerstein, 2014). Pornography typically portrays women as subordinate to men in workplace relationships (male executive, female secretary). Women submit to male sexual needs and appear most eager to pleasure them sexually. Pornography violates the traditional sexual script that sex should take place only between consenting adults in a married or a committed monogamous relationship (Wright & Donnerstein, 2014). Internet pornography depicts sex as driven solely by pleasure seeking and not associated with love, affection, or a committed relationship. Risky sexual behaviors are depicted in Internet pornography with infrequent condom use, sex with multiple partners, extravaginal sex and ejaculation, and often sex with at least 3 partners simultaneously. Studies (Johansson & Hammarén, 2007; Lo, Neilan, Sun, & Chiang, 1999; Rothman et al., 2012) have indicated that adolescent exposure to pornography is associated with more alternative sexual attitudes and behaviors such as having casual sex, anal sex, oral sex, group sex, and high-risk sex (multiple partners and no condom use).

Ybarra et al. (2011)) examined the link between pornography use and sexually aggressive behaviors in adolescents. More than 3,000 children between the ages of 10 and 15 years were surveyed regarding their intentional pornography use, perpetration of sexual aggression (in-person sexual assault, technology-based sexual harassment, and solicitation), and sexual aggression victimization. Nearly one fourth (23%) of youth reported intentional exposure to pornography in the past, and 5% reported perpetrating sexually aggressive behavior. Less than 5% of teens reported exposure to sexually violent pornography. Youth who reported intentional exposure to pornography were 6.5 times more likely to report perpetration of sexually aggressive behaviors when compared with youth not reporting intentional pornography use. Youth reporting exposure to sexually violent pornography were 24 times more likely to perpetrate sexually aggressive behaviors in comparison with their non–pornography viewing peers. This increased likelihood of engaging in sexually aggressive behaviors was not gender-specific; both boys and girls viewing pornography, especially sexually violent pornography, were much more likely to engage in sexually aggressive behaviors.

Studies of Internet pornography use by adults have solidified the knowledge that some individuals report a loss of control regarding their pornography use, accompanied by increasing pornography use and negative consequences in multiple areas of life such as academic, job functioning, and personal relationships (Duffy, Dawson, & dasNair, 2016). The actual prevalence of Internet pornography disorder (IPD) in the adult population is impossible to estimate because there is no agreement on the diagnostic criteria (Laier & Brand, 2017). It is important to note that IPD becomes a problem for only a small but significant number of individuals (Sniewski, Farvid, & Carter, 2018). There is a current argument among experts, on how to best classify addictive viewing of Internet pornography as a form of sex addiction (Kafka, 2014) or a specific type of Internet addiction (Young, 2008). Regardless of the classification, certain individuals appear to be at an increased risk of developing problematic pornography viewing. Individuals with underlying comorbidities such as depression or anxiety disorders (Laier & Brand, 2017; Wood, 2011), impulsivity (Grant & Chamberlain, 2015), compulsivity (Wetterneck et al., 2012), self-regulation deficits (Sirianni & Vishwanath, 2016), and high levels of narcissism (Kasper, Short, & Milam, 2015) are particularly vulnerable to develop problems with their pornography use. It is important to note that the majority of individuals who seek treatment for IPD are Caucasian (Kraus, Meshberg-Cohen, Martino, Quinones, & Potenza, 2015), believe their pornography use is a moral transgression (Grubbs, Volk, Exline, & Pargament, 2015), and report pornography exposure early in adolescence as well as participating in risky sexual behavior in adolescence (Doornwaard et al., 2016). Alexandraki, Stavropoulos, Burleigh, King, & Griffiths (2018)) in a longitudinal study of 648 adolescents at 16 years of age and then at 18 years of age found Internet pornography viewing to be a significant risk factor of the development of Internet addiction—the use of the Internet in a manner that is continuous and compulsive, resulting in negative consequences to everyday life. Evidence suggests that excessive and compulsive pornography use has effects on the brain similar to those seen in substance addictions, including a decline in working memory performance (Laier, Schulte, & Brand, 2013), neuroplasticity changes that reinforce use (Love, Laier, Brand, Hatch, & Hajela, 2015), and reduction in grey matter volume (Kühn & Gallinat, 2014). Magnetic resonance scans in adults have shown the brain activity of individuals who are self-perceived pornography addicts are comparable to those with substance dependence (Gola et al., 2017).

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The use of technology by children, especially mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers, has dramatically increased in recent years. Kabali et al. (2015)), in a study involving 0 to 4-year-olds recruited from a low-income clinic, stated that nearly all (96.6%) of the children had used a mobile device, 75% owned their device, andmost 2-year-olds used a mobile device regularly. It is a reality that the majority of pediatric nurse practitioners (PNPs) are providing care to children of all ages who are familiar with and often very sophisticated in regards to Internet technology.

Internet pornography is readily available to American children and adolescents. Studies have revealed that viewing pornography can result in a variety of negative consequences for both children and adolescents. It is crucial that PNPs feel comfortable and knowledgeable in addressing the issue of pornography viewing with caregivers and children. Rothman et al. (2017)) studied parental reaction to their young children (less than 12 years of age) viewing pornography. Many parents in this sample of 279 reported feeling paralyzed, unsure of how to respond to their child, and fearful of the potential impact on their child. The majority of the children (76%) viewed pornography online, 13% in print, and 10% on television. Nearly one fourth (24%) of parents reported that they felt their child’s pornography viewing was intentional. None of the parents reported that they found out about their child’s pornography viewing because they asked the child about the viewing. Parents also stated that they would be in favor of their child’s healthcare provider giving them guidance or pamphlets or directing them to other educational resources to assist them in better knowing how to talk to their children about pornography (Rothman et al., 2017).

PNPs must be poised to address the needs of parents and their children related to Internet pornography use. The first step in this process involves assessing child and adolescent use of online technology. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that pediatric health care providers ask adolescents and older children 2 technology-related questions at all well-child visits (Council on Communications and Media, 2010): how much time do you spend on the Internet and online social media each day?; and do you have access to the Internet in your bedroom? The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that adolescents limit media use to less than 2 hours a day (Barkin et al., 2008).

PNPs must stress how important it is that parents talk with their children about what they are viewing online and whom they are talking to online andencourage their children to be open and honest regarding their online activities. It is also important that parents develop an Internet safety plan to reduce the likelihood of exposure to sexual material on the home computer and mobile devices. Preventive software including filtering, blocking, and monitoring software should be installed (Ybarra, Finkelhor, Mitchell, & Wolak, 2009). Discuss with parents the importance of explaining to their child that they, as their parents, want to protect them from viewing content that is for adults only. Especially for young children, limit alone and unsupervised Internet use. Encourage Internet use in only public areas of the home. Caution parents that being too restrictive with older children and adolescents may lead them to be less open and honest regarding online behavior. Parents must also be cognizant of what they themselves are viewing online and protect their children from accessing any pornography or other adult content they may be viewing.

Although an Internet safety plan is essential, total prevention of access to online pornography is virtually impossible. Providing anticipatory guidance regarding child and adolescents exposure to pornography is crucial. Encourage parents to talk with their children and adolescents in an age-appropriate manner about pornographic content and encourage children and adolescents to come to the parent if they ever see anything online that is confusing or disturbing to them. This will help protect them if they accidentally come across such content. Reinforce the need for parents to have age-appropriate discussions with children and adolescents about sex, sexuality, and intimacy. Building this open relationship between parent and child will make it easier for the child to come to the parent with sexual questions or curiosities. See Box 3 for online resources available for parents to assist them with discussing pornography with their children and protecting them from pornography viewing.

BOX 3

Online resources for parents

Screening children and adolescents for pornography viewing should be a routine aspect of pediatric health care. For children younger than 12 years of age, the anogenital exam, which should be a part of all well-child exams, offers an appropriate opportunity to ask a few screening questions. Anogenital exams should include education about the concept of private parts and what the child should do if private parts are touched, and asking if anything like that has ever happened to them (Hornor, 2013). Also ask if they have ever seen pictures, movies, or videos of people without their clothes on. If the answer is yes, explore. Ask where they viewed the images, what the people without their clothes on were doing, whether anyone show them the images, and whether they viewed the images once or more than one time. Children less than 12 years of age repeatedly seeking pornography viewing require referral to a mental health provider for further exploration of the behavior. For adolescents 12 years of age and older, a discussion of sexual activity should include an assessment of possible pornography viewing; if affirmative to viewing, try to determine frequency of viewing. It is important to discuss healthy sexual intimacy with pornography viewing adolescents and stress that what they are viewing in pornography does not depict typical real-life intimate relationships. Adolescents disclosing problematic pornography viewing (excessive, disrupting school, social, or family life) will also need intervention with a mental health specialist versed in addressing the concern. Familiarity with local mental health resources will assist the PNP with making the most appropriate mental health referral.

Children under the age of 12 years engaging in PSB will need to be assessed for exposure to pornography and possible sexual abuse. A referral to child protective services is indicated to ensure the safety of the child. The child will need a forensic interview by an appropriately trained individual and a medical exam by an individual skilled in sexual abuse examinations. Knowledge of local resources is crucial. Depending on the chronicity and severity of the PSB, these children may also benefit from specialized mental health services, which include elements of trauma-informed care while also providing body education and safety.

Online pornography is readily available to American children and adolescents. Pornography viewing can result in a variety of adverse health consequences. PNPs should urge schools to provide comprehensive sex education programs that include principles of healthy intimate relationships as well as basic principles of Internet literacy (Council on Communications and Media, 2010). PNPs should also encourage and participate in research into the effect of sexual contact in online media on children and adolescents. By participating in governmental advocacy, PNPs can lobby for the implementation of stricter Internet regulation to better control child and adolescent access to online pornography. Finally, PNPs can make immediate differences in the lives of children and adolescents by incorporating practice behaviors to better assess for pornography exposure and provide appropriate intervention as needed. Pornography viewing is indeed a pediatric health care problem, and PNPs must feel comfortable and confident in addressing the problem.

Appendix B. Supplementary materials

CE TEST QUESTIONS

- 1.

Internet pornography differs from traditional pornography in which of the following ways?

- a.

Increased affordability

- b.

More easily accessed

- c.

Less anonymous

- d.

All the above

- e.

a and b

- a.

- 2.

Online pornography use is common in adolescent boys and just as common among adolescent girls.

- a.

True

- b.

False

- a.

- 3.

Factors predictive of child and adolescent pornography use include which of the following?

- a.

Male gender

- b.

Bisexual or gay male

- c.

Impulsive, thrill-seeking personality characteristics

- d.

All of the above

- a.

- 4.

Experiencing psychosocial traumas such as physical and sexual abuse can also be predictive of child and adolescent pornography viewing.

- a.

True

- b.

False

- a.

- 5.

Factors protective against adolescent pornography viewing include all except which of the following?

- a.

Strong religious beliefs

- b.

Higher pubertal stage of development

- c.

Higher parental education

- d.

Healthier family relationships

- a.

- 6.

Concerns regarding child and adolescent pornography viewing center around which of the following?

- a.

The content of the pornography

- b.

The ability of the child/adolescent to separate pornography fiction from sexual reality

- c.

Easy access to pornography

- d.

All the above

- a.

- 7.

Wright’s sexual script theory explains the socializing effect of pornography via which of the following three A’s?

- a.

Accessibility

- b.

Acquisition

- c.

Activation

- d.

Application

- e.

a, b, and d

- f.

b, c, and d

- a.

- 8.

Possible consequences of adolescent online pornography viewing include which of the following?

- a.

High-risk sexual behaviors

- b.

Sexually aggressive behaviors

- c.

Homosexuality

- d.

Human trafficking

- e.

a and b

- f.

All the above

- a.

- 9.

Which of the following are included in the definition of problem sexualized behaviors in children?

- a.

Children less than 7 years of age when behaviors begin

- b.

Sexual knowledge beyond what would be expected for the child’s age and developmental level

- c.

Children engaging in sophisticated sexual acts

- d.

Children less than 12 years of age when behaviors begin

- e.

a, b, and c

- f.

b, c, and d

- a.

- 10.

Excessive pornography use can result in brain changes similar to those found in substance addictions.

- a.

True

- b.

False

- a.

Answers available online at ce.napnap.org.

References

- Alexandraki, K., Stavropoulos, V., Burleigh, T.L., King, D.L., and Griffiths, M.D. Internet pornography viewing preference as a risk factor for adolescent Internet addiction: The moderating role of classroom personality factors. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2018; 7: 423–432

|

- Council on Communications and Media. American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy statement–Sexuality, contraception, and the media. Pediatrics. 2010; 126: 576–582

|

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2018). Children and media tips from the American Academy of Pediatrics. Retrieved from https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/news-features-and-safety-tips/Pages/Children-and-Media-Tips.aspx

- Australian Government Office of the eSafety Commissioner (2019). Online pornography: A guide for parents and carers. Retrieved from https://www.esafety.gov.au/parents/big-issues/online-pornography

- Baams, L., Overbeek, G., Dubas, J.S., Doornwaard, S.M., Rommes, E., and Van Aken, M.A. Perceived realism moderates the relation between sexualized media consumption and permissive sexual attitudes in Dutch adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015; 44: 743–754

|

- Barkin, S.L., Finch, S.A., Ip, E.H., Scheindlin, B., Craig, J.A., and Steffes, J. Is office-based counseling about media use, timeouts, and firearm storage effective? Results from a cluster-randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008; 122: e15–e25

|

- Beyens, L., Vandenbosch, L., and Eggermont, S. Early adolescent boys’ exposure to Internet pornography: Relationships to pubertal timing, sensation seeking, and academic performance. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2015; 35: 1045–1068

|

- Bleakley, A., Hennessy, M., and Fishbein, M. A model of adolescents’ seeking of sexual content in their media choices. Journal of Sex Research. 2011; 48: 309–315

|

- Bridges, A.J., Wosnitzer, R., Scharrer, E., Sun, C., and Liberman, R. Aggression and sexual behavior in best-selling pornography videos: A content analysis update. Violence Against Women. 2010; 16: 1065–1085

|

- Brown, J.D., Halpern, C.T., and L’Engle, K.L. Mass media as a sexual super peer for early maturing girls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005; 36: 420–427

|

- Brown, J.D. and L’Engle, K.L. X-rated: Sexual attitudes and behaviors associated with U.S. early adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit media. Communication Research. 2009; 36: 129–151

|

- Chaffin, M., Berliner, L., Block, R., Johnson, T.C., Friedrich, W.N., Louis, D.G., …, and Madden, C. Report of the ATSA task force on children with sexual behavior problems. Child Maltreatment. 2008; 13: 199–218

|

- Chen, A., Leung, M., Chen, C., and Yang, S.C. Exposure to Internet pornography among Taiwanese adolescents. Social Behavior and Personality. 2013; 41: 157–164

|

- Collins, R.L., Strasburger, V.C., Brown, J.D., Donnerstein, E., Lenhart, A., and Ward, L.M. Sexual media and childhood well-being and health. Pediatrics. 2017; 140: S162—S166

|

- Cooper, A. Sexuality and the Internet: Surfing into the new millennium. CyberPsychology and Behavior. 1998; 1: 187–193

|

- Dillard, R., Maguire-Jack, K., Showalter, K., Wolf, K.G., and Letson, M.M. Abuse disclosures of youth with problem sexualized behaviors and trauma symptomology. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2019; 88: 201–211

|

- Doornwaard, S.M., van den Eijnden, R.J., Baams, L., Vanwesenbeeck, I., and ter Bogt, T.F. Lower psychological well-being and excessive sexual interest predict symptoms of compulsive use of sexually explicit internet material among adolescent boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016; 45: 73–84

|

- Duffy, A., Dawson, D.L., and das Nair, R. Pornography addiction in adults: A systematic review of definitions and reported impact. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2016; 13: 760–777

|

- Flood, M. Exposure to pornography among youth in Australia. Journal of Sociology. 2007; 43: 45–60

|

- Gola, M., Wordecha, M., Sescousse, G., Lew-Starowicz, M., Kossowski, B., and Wypych, M. Can pornography be addictive? An fMRI study of men seeking treatment for problematic pornography use. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017; 42: 2021–2031

|

- Gossett, J.L. and Byrne, S. ‘Click here’-a content analysis on Internet rape sites. Gender and Society. 2002; 16: 689–709

|

- Grant, J. and Chamberlain, S. Psychopharmacological options for treating impulsivity. Psychiatric Times. 2015; 32: 58–61

|

- Grubbs, J.B., Volk, F., Exline, J.J., and Pargament, K.I. Internet pornography use: Perceived addiction, psychological distress, and the validation of a brief measure. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2015; 41: 83–106

|

- Hardy, S.A., Steelman, M.A., Coyne, S.M., and Ridge, R.D. Adolescent religiousness as a protective factor against pornography use. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2013; 34: 131–139

|

- Hasking, P.A., Scheier, L.M., and Abdallah, A.B. The three latent classes of adolescent delinquency and the risk factors for membership in each class. Aggressive Behavior. 2011; 37: 19–35

|

- Hornor, G. Child maltreatment: Screening and anticipatory guidance. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2013; 27: 242–250

|

- Internet matters.org (2019). Helping children deal with exposure to online porn. Retrieved from https://www.internetmatters.org/issues/online-pornography/protect-your-child/

- Johansson, T. and Hammaré, N. Hegemonic masculinity and pornography: Young people’s attitudes toward and relations to pornography. Journal of Men’s Studies. 2007; 15: 57–70

|

- Kabali, H.K., Irigoyen, M.M., Nunez-Davis, R., Budacki, J.G., Mohanty, S.H., Leister, K.P., and Bonner, R.L. Exposure and use of mobile media devices by young children. Pediatrics. 2015; 136: 1044–1050

|

- Kafka, M.P. What happened to hypersexual disorder?. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014; 43: 1259–1261

|

- Kasper, T.E., Short, M.B., and Milam, A.C. Narcissism and internet pornography use. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2015; 41: 481–486

|

- Kraus, S.W., Meshberg-Cohen, S., Martino, S., Quinones, L.J., and Potenza, M.N. Treatment of compulsive pornography use with naltrexone: A case report. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015; 172: 1260–1261

|

- Kühn, S. and Gallinat, J. Brain structure and functional connectivity associated with pornography consumption: The brain on porn. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014; 71: 827–834

|

- Laier, C. and Brand, M. Mood changes after watching pornography on the Internet are linked to tendencies towards Internet-pornography-viewing disorder. Addictive Behaviors Reports. 2017; 5: 9–13

|

- Laier, C., Schulte, F.P., and Brand, M. Pornographic picture processing interferes with working memory performance. Journal of Sex Research. 2013; 50: 642–652

|

- Livingstone, S. and Smith, P.K. Annual research review: Harms experienced by child users of online and mobile technologies: The nature, prevalence and management of sexual and aggressive risks in the digital age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2014; 55: 635–654

|

- Lo, V., Neilan, E., Sun, M., and Chiang, S. Exposure of Taiwanese adolescents to pornographic media and its impact on sexual attitudes and behaviour. Asian Journal of Communication. 1999; 9: 50–71

|

- Love, T., Laier, C., Brand, M., Hatch, L., and Hajela, R. Neuroscience of Internet pornography addiction: A review and update. Behavioral Sciences. 2015; 5: 388–433

|

- Luder, M.T., Pittet, I., Berchtold, A., Akré, C., Michaud, P.A., and Surís, J.C. Associations between online pornography and sexual behavior among adolescents: Myth or reality?. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011; 40: 1027–1035

|

- Malamuth, N., Linz, D., Yao, M., and Amichai-Hamburger. The Internet and aggression: Motivation, disinhibitory and opportunity aspects. The social net: Human behavior in cyberspace. Oxford University Press, New York, NY; 2005: 163–191

|

- Matković, T., Cohen, N., and Štulhofer, A. The use of sexually explicit material and its relationship to adolescent sexual activity. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2018; 62: 563–569

|

- Mesch, G.S. Social bonds and Internet pornographic exposure among adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2009; 32: 601–618

|

- Mesman, G.R., Harper, S.L., Edge, N.A., Brandt, T.W., and Pemberton, J.L. Problematic sexual behavior in children. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2019; 33: 323–331

|

- Mitchell, K.J. and Wells, M. Problematic Internet experiences: Primary or secondary presenting problems in persons seeking mental health care?. Social Science and Medicine. 2007; 65: 1136–1141

|

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network (2009). Understanding and coping with sexual behavior problems in children: Information for parents and caregivers. Retrieved from https://ncsn.org/sites/default/files/resources//understanding_coping_with_sexual_behavior_problems.pdf

- Peter, J. and Valkenburg, P.M. Adolescents and pornography: A review of 20 years of research. Journal of Sex Research. 2016; 53: 509–531

|

- Prevent Child Abuse America (2019). Understanding the effects of pornography on children. Retrieved from https://preventchildabuse.org/resource/understanding-the-effects-of-pornography-on-children/

- Reid Chassiakos, Y.L., Radesky, J., Christakis, D., Moreno, M.A., Cross, C., and Council on Communications and Media. Children and adolescents and digital media. Pediatrics. 2016; 138: 1–16

|

- Rothman, E.F., Decker, M.R., Miller, E., Reed, E., Raj, A., and Silverman, J.G. Multi-person sex among a sample of adolescent female urban health clinic patients. Journal of Urban Health. 2012; 89: 129–137

|

- Rothman, E.F., Paruk, J., Espensen, A., Temple, J.R., and Adams, K. A qualitative study of what US parents say and do when their young children see pornography. Academic Pediatrics. 2017; 17: 844–849

|

- Ševčíková, A., Šerek, J., Barbovschi, M., and Daneback, K. The roles of individual characteristics and liberalism in intentional and unintentional exposure to online sexual material among European youth: A multilevel approach. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2014; 11: 104–115

|

- Shek, D.T.L. and Ma, C.M.S. Using structural equation modeling to examine consumption of pornographic materials in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. International Journal on Disability and Human Development. 2014; 13: 239–245

|

- Short, M.B., Black, L., Smith, A.H., Wetterneck, C.T., and Wells, D.E. A review of internet pornography use research: Methodology and content from the past 10 years. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour and Social Networking. 2012; 15: 13–23

|

- Sirianni, J.M. and Vishwanath, A. Problematic online pornography use: A media attendance perspective. Journal of Sex Research. 2016; 53: 21–34

|

- Sniewski, L., Farvid, P., and Carter, P. The assessment and treatment of adult heterosexual men with self-perceived problematic pornography use: A review. Addictive Behaviors. 2018; 77: 217–224

|

- Strasburger, V.C., Jordan, A.B., and Donnerstein, E. Children, adolescents, and the media: Health effects. (vii)Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2012; 59: 533–587

|

- Strouse, J.S., Goodwin, M.P., and Roscoe, B. Correlates of attitudes toward sexual harassment among early adolescents. Sex Roles. 1994; 31: 559–577

|

- Tsaliki, L. Playing with porn: Greek children’s explorations in pornography. Sex Education. 2011; 11: 293–302

|

- Tsitsika, A., Critselis, E., Kormas, G., Konstantoulaki, E., Constantopoulos, A., and Kafetzis, D. Adolescent pornographic internet site use: A multivariate regression analysis of the predictive factors of use and psychosocial implications. Cyberpsychology and Behavior. 2009; 12: 545–550

|

- Wetterneck, C.T., Little, T.E., Rinehart, K.L., Cervantes, M.E., Hyde, E., and Williams, M. Latinos with obsessive-compulsive disorder: Mental healthcare utilization and inclusion in clinical trials. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2012; 1: 85–97

|

- Wingood, G.M., DiClemente, R.J., Harrington, K., Davies, S., Hook, E.W., and Oh, M.K. Exposure to X-rated movies and adolescents’ sexual and contraceptive-related attitudes and behaviors. Pediatrics. 2001; 8: 473–486

|

- Wolak, J., Mitchell, K., and Finkelhor, D. Unwanted and wanted exposure to online pornography in a national sample of youth Internet users. Pediatrics. 2007; 119: 247–257

|

- Wood, H. The Internet and its role in the escalation of sexually compulsive behaviour. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy. 2011; 25: 127–142

|

- Wright, P.J. Mass media effects on youth sexual behavior Assessing the Claim for Causality. Annals of the International Communication Association. 2011; 35: 343–385

|

- Wright, P.J. and Donnerstein, E. Sex online: Pornography, sexual solicitation, and sexting. Adolescent Medicine: State of the Art Reviews. 2014; 25: 574–589

|

- Wright, P.J. and Štulhofer, A. Adolescent pornography use and the dynamics of perceived pornography realism: Does seeing more make it more realistic?. Computers in Human Behavior. 2019; 95: 37–47

|

- Ybarra, M.L., Finkelhor, D., Mitchell, K.J., and Wolak, J. Associations between blocking, monitoring, and filtering software on the home computer and youth-reported unwanted exposure to sexual material online. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2009; 33: 857–869

|

- Ybarra, M.L. and Mitchell, K.J. Exposure to internet pornography among children and adolescents: A national survey. Cyberpsychology and Behavior. 2005; 8: 473–486

|

- Ybarra, M.L., Mitchell, K.J., Hamburger, M., Diener-West, M., and Leaf, P.J. X-rated material and perpetration of sexually aggressive behavior among children and adolescents: Is there a link?. Aggressive Behavior. 2011; 37: 1–18

|

- Yoder, J., Dilliard, R., and Leibowitz, G.S. Family experiences and sexual victimization histories: A comparative analysis between youth sexual and non-sexual offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2018; 62: 2917–2936

|

- Young, K.S. Internet sex addiction: Risk factors, stages of development, and treatment. American Behavioral Scientist. 2008; 52: 21–37

|

Biography

Gail Hornor, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Center for Family Safety and Healing, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH.